Remembering Larry Halprin

Last Wednesday I headed to the Bay Area for our conference, Landscapes for Living: Postwar Years in Northern California, and to visit with Larry Halprin. We had planned to have lunch together on Thursday. I imagined us drinking Arnold Palmers together (something he had introduced me to years earlier), he would order dessert which he was not supposed to have, and we would preview edits from the forthcoming oral history project we were doing about him. That evening he took a bad fall and by Sunday morning Halprin would pass away at his home in Kentfield, California, at the age of 93.

By Saturday afternoon at our conference, four former Halprin employees and his stone mason would take the stage when an announcement about Halprin’s health was made. A hush came over the audience, one speaker openly wept, and the fragility of the legacy became abundantly clear.

Ever since 1970 when Ada Louise Huxtable dubbed Lawrence Halprin’s Auditorium Forecourt Fountain in Portland, Oregon, “one of the most important urban spaces since the Renaissance,” much has been written about this maverick trailblazer who defied convention. Unlike other Modernists of his era, and always looking back while looking ahead, Halprin surprisingly describes himself on the dust jacket to his urban treatise, Cities (1963) as “a landscape architect in the tradition of the Olmsteds.”

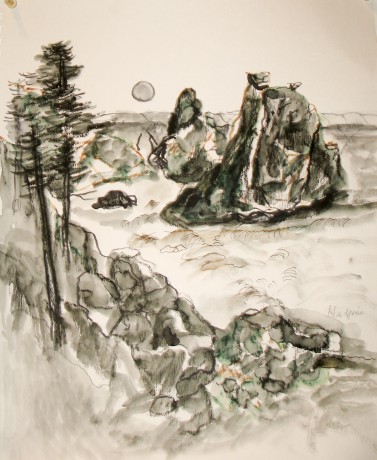

It was just two months earlier that his office had celebrated 60 years of practice in the Bay Area. At the end of this November it was scheduled to close its doors for good, and Larry would apprehensively retire. With his richly illustrated autobiography now complete (to be published by the University of Pennsylvania Press) and a number of his celebrated designs such as the Portland Chain of Open Spaces (which now has its own Conservancy) experiencing a newfound rediscovery and renaissance, Larry would retire to his home with frequent visits to Sea Ranch to once again be a Sunday painter, enjoy nature and his grandchildren.

It was just four years ago, still going strong, at the age of 89, that Halprin’s office would complete three capstone projects: the astonishing tri-fecta of Lucas Studios at the Presidio, Stern Grove, and Yosemite Falls. Ironically, it was because these projects were still to be built that scholars were late to evaluate Halprin’s work, and unlike Dan Kiley or Philip Johnson who both would live to see multiple National Historic Landmark designations listed during their lifetime, Halprin was not as lucky and instead would witness the demolition and redesign of a number of his projects from the 1970s, including Nicolette Mall in Minneapolis, Skyline Park in Denver and the sculpture garden at the Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond. In addition, two of his revolutionary 1976 Bicentennial Commission projects – Seattle’s Freeway Park (the first park over a freeway in the U.S.) and Fort Worth’s Heritage Plaza (the progenitor of the outdoor rooms that would be employed at the FDR Memorial) would also be targets for less than sensitive design proposals that would threaten their design integrity. In fact, Heritage Plaza has been closed to the public for the past two years surrounded by a chain link fence.

It was this shared concern to guide these landscapes into the future and give them a voice that served as a personal bond between us. Since 2003, we have been filming Larry at his office in downtown San Francisco, and Larkspur, California, as well as at his home and dance deck in Kentfield and at Sea Ranch. In one of our 2003 interviews Larry reflected on his threatened work, noting “like anything, I treasure them all just like you treasure children. Some of your children are more problems than others. But even so, you love them. I don't think from my point of view that there's much difference in my attitude about my children and my works of art.”

Optimistic, sensitive, thoughtful, cherubic, his love of design, people, the shaping of cities and spaces, and the blurring of lines between his personal and professional life energized Larry.

A couple of weeks before Halprin passed away, Heritage Plaza was recommended by the Texas Historical Commission for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. It is now at the National Park Service awaiting approval by the Keeper of the Register. Let the celebration and rediscovery of his legacy begin.