Pioneer Information

Born in New York City in 1913, Reich’s early childhood gave him a sense of independence and appetite for learning that characterized his entire life. From Cornell University, he earned a B. S. in horticulture in 1934 and a PhD in 1941, studying education. Reich was hired to teach landscape architecture courses by the Dean of Agriculture at Louisiana State University, and spent his career there, founding an independent landscape architecture department in 1946 and shepherding it for more than 60 years. His courses, ranging from design theory to career planning, encouraged students to think creatively and pursue personal interests in the context of their professional studies. Reich’s design teaching followed Modernist principles, which he learned during a sabbatical year spent with Garrett Eckbo in the 1950s.

Throughout Reich’s career as an educator he also ran a professional practice; Reich and Associates was one such partnership between Reich and his son Bill, a landscape architect. The firm’s diverse work includes the Baton Rouge Riverside Centroplex, Lake Claiborne State Park, University Methodist Church Complex, and Mountain Lake Sanctuary in Lake Wales, Florida.

In 1992 Reich was awarded the ASLA Medal. He was again honored by the ASLA with the Jot D. Carpenter Teaching Medal in 2005. Reich passed away on July 31, 2010, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

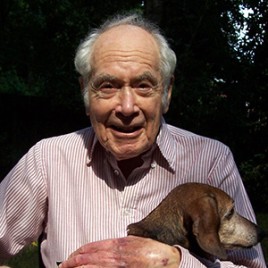

Robert S. Reich, often referred to as Doc, was born in New York City on March 22, 1913. Reich was the only child of Ulysses and Adele Reich. His mother was a school teacher in the New York public schools; his father grew up in lower Manhattan where his family ran a hotel, The Cambridge, which would eventually become the Astor, and later the Waldorf-Astoria, long after the family had lost the hotel to creditors.

Reich’s colorful father Ulysses provided young Robert and his school friends with tickets to Broadway shows. Reich’s early schooling in a New York City Montessori-style school gave him a sense of independence and love for learning that characterized him as a young boy. This independence of thought and voracious intellect would become defining traits of his personality as an adult.

Reich spent summers either on Long Island, or later at Rockville Center and Lynbrook. Reich was fascinated with trains at an early age and his lust for travel would lead to a belief that travel was one of the best teachers of the kind of observation necessary for one to become a successful designer.

In the third grade, the Reich family moved to New Rochelle, seeking a smaller community in which to raise their son. As a cross-country runner, he was “great at coming in last,” as he recounts, because he was “looking at and enjoying the landscape.” Reich says that his team captain always encouraged him despite his poor performance, and that this example of leadership by encouragement and belief in the potential of “late bloomers” became important to him as a leader of groups in his service in the army and later as an educator.

An accidental occurrence during high school was responsible for Reich’s exposure to landscape architecture. He won an essay contest and was invited to the home of the prize donor, where he was amazed by her garden of lovely plants. “I became greatly interested in her plantings, and the first thing I knew, through her interests, I decided to go to Cornell to study plants.”

At Cornell University, Reich earned a Bachelor of Science degree in horticulture in 1934 and a doctorate in 1941, studying education. His Cornell experiences would shape his life’s work; his commitment to the power of education led him to his career choice of educator, and his strong foundation in plant sciences made him a persistent advocate for plants as the signature material of the profession.

Upon graduation, Reich was hired to teach courses in landscape architecture by the Dean of Agriculture at Louisiana State University (LSU). He arrived at the train station in Baton Rouge one night in 1941, and was in the classroom teaching the following morning. He has been there nearly continuously since that morning, eventually founding an independent department in 1946, moving it from agriculture to the College of Design, elevating its status to a School, and lobbying for a new building. Initially, Reich had only intended to stay in the South for a year, and planned to return to Cornell after that. However, a chance meeting with a young librarian, Helen Adams, altered his life plans permanently, and Cornell’s loss was LSU’s great fortune.

Reich proposed and they were wed shortly after his return from service in World War II. Helen became Reich’s partner in running the department as well as his practice. Her untimely death in 1968 was a terrible blow to Reich as they had shared most aspects of their lives so closely, particularly their devotion to their faith.

Reich endowed scholarships in his wife’s name, and as their four children grew up, Reich poured more and more energy and attention into his university “family”—the students and the faculty in landscape architecture, and the congregation of the University Methodist Church. Reich was concerned for the welfare of students and faculty beyond the academic arena and many alumni continue to correspond with “Doc” as extended family. For decades he has prepared a floral arrangement for the altar each Sunday morning, using the wildflowers and foliage of the native vegetation from rural roadsides. Reich officially retired from teaching in 1983, at the age of 70, forced by a mandatory university retirement policy. He has taught part-time without compensation since then, serving as professor emeritus and continuing to influence classes of students who enroll in his seminars, travel on field trips with him, and attend ice-cream socials in his home. This past semester, Reich conducted his “enrichment” seminar for upperclassmen in landscape architecture at St. James retirement home, where he had recently moved. The students came to him, and seemed to enjoy the experience.

Reich’s goal as educator and department head from the onset was to have landscape architecture recognized as a design profession, not as an extension of horticulture; and to make the services of the profession known to the residents and communities of the state. There was only one other landscape architect in Louisiana when Reich came to LSU, and few in the region at the time.

During the 1950s Reich became disillusioned with the pedagogical methods that he found being used at many schools of landscape architecture, and the reliance on the Beaux-Arts vocabulary that he saw in the profession, which he felt suppressed individuality. He believed that there should be a more creative approach and was considering leaving the profession when he came across Garrett Eckbo’s* just-published 1950 book, Landscape for Living. The book struck a chord, and Reich requested a sabbatical to spend time in California in Eckbo’s office. As a consequence of Reich’s working so intensely with Eckbo he was not only exposed to innovative projects in the language of Modernism as applied to residential design, but also to Eckbo’s pioneering commitment to social justice and to environmental conservation.

After this work experience, Reich returned to LSU energized and determined. Reich explained that Eckbo had confirmed his belief in individual creativity: that one should never copy anyone else’s work, that each person’s life experience and interpretation of a landscape was a critical element in the design process. Reich refined the curriculum, so that students were encouraged to take free electives, broadening their perspectives beyond the professional courses to include humanities, allied arts, and, allowing students to pursue their personal interests beyond landscape architecture. He incorporated travel as a major component of the curriculum, with annual trips to the east and west coasts required before graduation. As recently as 2006, Reich escorted a class of students on a field trip to Texas to tour projects and visit offices of alumnae. Enrichment trips abroad, to Europe, Asia, and Central and South America were offered during the summers. Reich recognized that many of his students had never left the state of Louisiana, and that these opportunities to see “the world” would benefit students in immeasurable ways beyond their college years.

Reich’s personal teaching included courses in design theory, site planning, plant materials, planting design, landscape history, and career planning. In teaching design, he used Modernist ideas. His required Saturday morning field trips via bicycle to tour landscape projects served as a living laboratory, in which students experienced first-hand the work of their teacher and other faculty and professionals in the community. Reich would direct the group of students through these landscapes and residences, pointing out how he had created the “gasp” view from the front entrance straight through the interior spaces and out the back of the house to the landscape garden. Or he would point out the screening effect of the “baffle” of bamboo or parasol trees that separated one outdoor room from the next. This direct illustration of the theory carried from classroom to the built project stayed with students in a way that textbook teaching or slideshow illustrations did not.

In Reich’s history courses, he included detailed units on the landscapes of the Orient long before there were published texts on the subject or general agreement on the significance of this material for the education of a designer practicing primarily in the Western world. Reich knew that he was preparing students for international practice, and he was particularly drawn to the tenets of Oriental design in his own practice and design aesthetic, as were the members of the California School. Not only was Reich one of the first landscape architects in the state of Louisiana to be trained and practice, but his progressiveness and contact with the larger concept of professional practice earned him the title of the “father of landscape architecture in Louisiana.”

Throughout Reich’s career as an educator, he ran a professional practice with several different partners; today Reich and Associates is a partnership between Reich and his son Bill, a landscape architect. Over the years, the firm’s work has included a wide range of project types including residential commissions, community master plans, state parks, and large municipal projects. Projects in which he has played a major role include the Baton Rouge Riverside Centroplex, Lake Claiborne State Park, St. Aloysius Catholic Church, University Methodist Church Complex, and Mountain Lake Sanctuary in Lake Wales, Florida. Many students have had the opportunity to gain professional experience by working in the office as interns while in school or after graduation. On July 15, 2010 Reich’s final built project was completed and dedicated. He attended the ribbon-cutting for the restored “Cathedral” of LSU Hilltop Arboretum. This open space shaded by tall canopy trees had been devastated by several hurricanes, and Reich’s daughter and her husband, Betsy and Tron Thomas, had underwritten its restoration. The plans were developed by Reich, Doug Reed, and Wayne Womack, and Reich was honored at the dedication, where he said, “This is so beautiful. I’d like to stay here forever.”

Reich holds LSU’s highest teaching honor, Alumni Professor, and in 1992 he was awarded ASLA’s highest honor, the ASLA Medal. In 2005, he was again honored by the ASLA with the Jot D. Carpenter Teaching Medal.

Reich’s legacy as an educator has been his insistence that teaching should aim to “graduate educated, thinking people, not just landscape architect technologists.” Reich recognized that the pace of change in the modern world made it impossible to expose a student in a limited number of years to all of the possible information and situations that would be needed or encountered in practice. His belief was in helping the individual realize his or her potential as a problem-solver, and helping the student gain the self-confidence to become a leader and a contributing member of the communities he or she would join. Reich strove for nearly three-quarters of a century to foster an educational environment that remained relevant to the particular social and cultural issues of the time.

Reich’s remarkable zest for life is indeed contagious. He exercised daily in the university swimming pool, and rode his bicycle to work and home. Reich’s uncanny ability to remain open to the thinking of the time has allowed him to continue to relate to students and faculty alike into his ninth decade of life, a quality that has meant that he continues to graciously participate in the growth and evolution of the school that he founded over 60 years ago.

Reich died shortly after 4:00 PM Saturday, July 31, following a brief illness. He was 97 years old.

References

“A Voice from Landscape Architecture: The Life and Work of Dr. Robert S. Reich.” Produced by Chad Danos, project of the Louisiana Chapter ASLA, Creative Media Solutions, 2000.

Robert S. Reich, Autobiographical Notes (unpublished), 1999.

Public Landscapes

Baton Rouge Centroplex Repentance Park, 275 River Road South Baton Rouge, LA

St. Aloysius Catholic Church, 2025 Stuart Avenue Baton Rouge, LA

University United Methodist Church, 3350 Dalrymple Drive Baton Rouge, LA

St. Timothy United Methodist Church, Mandeville, LA

All photos by Brian Goad, ASLA.

Comments

By Susan Crook, ASLA August 18, 2010

The partnership of Doc Reich and Helen Adams during WWII reminds me of that of Laval and Rachel Morris at Utah State University. Rachel, also a landscape architect, took over Laval's teaching and department head duties - at no salary - while he served in the Army camouflaging military bases on the west coast. Laval trained at Harvard, returning after the Harvard Rebellion to complete his Master's degree, and bringing modernism to Utah landscape architecture education and practice. Student field trips included visits with Tommy Church in San Francisco. Church's influence can be seen in some gardens in Utah, though virtually no documentation exists as to who designed them.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Suzanne L. Turner, FASLA, is an LSU professor emerita of landscape architecture and board member of the Cultural Landscape Foundation.