Race and Cultural Landscapes: A Conversation With Kofi Boone

Editor’s note: ‘Race and Cultural Landscapes’ is a series of one-on-one conversations with thought-leaders around the nation about how issues of race and history are represented and evoked in cultural landscapes (see Part 1 and Part 2 ). The aim of the series is to shed light on these complex issues via thoughtful questions and dialogue. In this third conversation in the series, Kofi Boone, ASLA, associate professor of landscape architecture at North Carolina State University’s College of Design, talks with TCLF about the need for an environmental-justice perspective on cultural landscapes.

Can you begin by unpacking the term “environmental justice”?

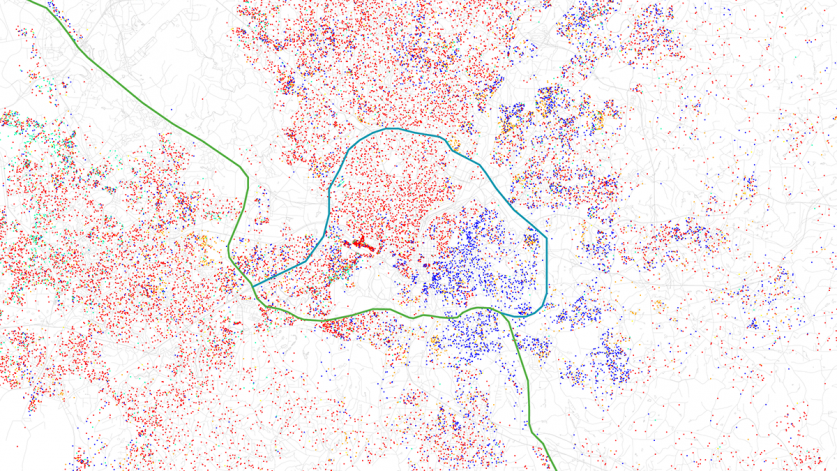

In 1987 the United Church of Christ published a report titled “Toxic Waste and Race,” which coined the term ‘environmental racism’ referring to the correlation between Black communities and proximity to toxic waste sites. The report gave evidence that race (not income, education level, or other characteristics) was the most accurate predictor of exposure to environmental hazards. The environmental justice movement centers around dismantling and combating environmental racism. Furthermore, it focuses on the decreased access to benefits, like open space, faced by communities of color. Environmental justice is also a global framework that encompasses climate justice—the correlation between race and increased impact of climate change. These movements are gaining currency in professions dealing with the built environment, including landscape architecture, but there is still much to be done to reverse the legacy of racism that continues to determine how and where many people live.

You have criticized neoliberalism for co-opting design activism, which has led to some designers expressing reluctance about engaging with the state. Can you explain your criticism?

The current neoliberal climate can be traced to the push to eliminate the Great Society programs championed by former President Lyndon Johnson. Part of that effort included a debate on whether it is the government’s role to “solve” social issues, and whether “big government programs” were more effective than private industry and individual responsibility in doing so. This worldview makes the claim that private industry has greater incentives to deliver services as compared to the government because an industry is motivated by both profit and competition. Since most of landscape architecture is a fee-for-service field, this thinking aligns with how landscape architects broadly view their roles as consultants and technical experts. And many students I teach believe that neoliberalism and private industry can indeed have a greater impact in creating societal and environmental change. It is, however, important to recognize that the political and economic consequences of neoliberalism is divestment from governments, a reduction in tax revenues, the relaxation of significant social and environmental protections, and a general resistance to strategies that don’t bring profit.

Do you believe that environmental racism can be dismantled by private-sector entities and the market?

Corporations still see environmental costs as “externalities” to their business models; this results in fewer protections for the socially and environmentally vulnerable. Major legislative advances, like the Civil Rights laws or environmental-protection legislation such as the Clean Water Act, came from government action, not the private sector. These advances came at a time when people considered themselves to be primarily citizens with rights rather than consumers with purchasing power. It seems a little naïve, but my hope is that landscape architects will consider the combination of a solutions-based approach, with state engagement, as a viable career path to better governance.

Jelani Cobb pointed out that “the myth of White Supremacy is the lack of recognition of mutuality.” Your review of the book Cultural Landscape Heritage in Sub-Saharan Africa in Landscape Architecture Magazine also touched upon that argument. How do the histories of European colonialism affect our understanding of cultural landscapes?

When I heard Dr. Cobb make that statement at Howard University, it really resonated with me. Iconic European works of landscape architecture, like André Le Nôtre’s Gardens of Versailles, were being created at the same time as the European colonization of Africa and Asia. Colonial rule was coupled with devaluing the cultural practices of the exploited peoples. That’s why the formal gardens and grounds of slave masters is “landscape architecture,” but the entire plantation, like Middleton Place in South Carolina, which replicated African technologies, is not recognized as such. In this example, the concept of mutuality would require the recognition of the entire endeavor as landscape architecture. But the omission is in part due to the trauma inflicted by revisiting the horrors of colonialism and slavery—reckoning with them, in fact—and that is more than some people want to deal with.

Your article “Black Landscapes Matter” (Ground Up: Journal of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning) discusses the fact that African American landscapes are often not considered “designed” and are categorized instead as vernacular. How does the current framework of landscape architecture fall short in this regard?

Landscape architecture is a relatively young academic and professional discipline that is negotiating its role alongside architecture and other disciplines. For this reason, defining the boundaries of landscape architecture has been a significant exercise. The exclusionary nature of the canon of landscape architecture is in part reflective of how arbiters define the profession. Landscapes, particularly in the American context, are impossible to discuss holistically without referencing the genocide of native people and three centuries of free labor by enslaved Africans. Africans were, in fact, sometimes “selected” for enslavement due to their deep landscape knowledge; the rice farmers of West Africa, for example, who had perfected rice growing, were specifically transported to and enslaved in South Carolina because of their unique expertise. Given these histories, one effect of this systemic devaluation has been to influence the very definitions of “Design” versus “Craft.” And this bias continues to valorize European and American cultural landscapes while “exoticizing” and “othering” traditions in Asia and Africa. The imperative here is that landscape architecture is a global profession, and we are approaching a tipping point where most schools and practices will not be in America or Europe. So we are in a critical moment with a manifest need to grapple with professional definitions.

Can you elaborate on the term “cross-cultural competence” in light of your teaching in West Africa and as co-director of the College of Design’s Ghana Study Abroad Program?

The idea is adapted from Deardorff’s Pyramid model of Intercultural Competencies in which he attempted to define a framework for skills development resulting in a mutually beneficial relationship between people from different cultures. Cross-cultural competency is measured by how both local and visitor collaborators can communicate an understanding of shared knowledge about each other, how they demonstrate an improved interpersonal skill set, how their interactions shape their attitudes about each other, and, most importantly, result in positive outcomes. This line of thinking radically altered how we designed the Ghana program in 2011 and 2014.

For example, in 2014 we worked in partnership with a Ghanaian group called the Mmofra Foundation. The group owned a private site in Accra, the capital city, and was interested in creating a prototype for an educational play that reinforced local cultural traditions. In America, we interpret their requirements as “park design,” but in Ghana, the idea of a “park” is a British colonial idea. Instead, they wanted to pursue outdoor spatial planning and design based on indigenous ideas. This meant that American students needed Ghanaians to expose them to a wide array of cultural experiences before involving them in the actual project. The exercise forced students to embrace small interventions to test ideas and think in incremental ways instead of using top-down master planning. It also created situations in which participants had to do the hard work of cross-cultural communication and negotiation.

The failure to adequately address a site’s historic context is sometimes cited as one of the leading reasons that so few cultural landscapes associated with African American history achieve the national historic designation. How can historic criteria be altered to be more inclusive?

I think we need a two-pronged approach to address this issue. The first concerns building capacity at the local level. Many spaces of Black history are under-resourced and lack the technical expertise needed to prepare documentation in support of historic designation. By building capacity through institutions, we can create new knowledge, make best practices available to the communities, and engage in cataloging, documenting, mapping, and research. Our recent work in Princeville, North Carolina (featured in TCLF’s Landslide 2018: Grounds for Democracy) is a great example of this.

The second effort focuses on challenging the values of local historic preservation boards, which, in my opinion, favor artifacts over the story. Black towns and landmarks were often sited in floodplains for want of better land, which means that many structures are often severely damaged by extreme weather events. Damaged structures cannot meet the “integrity” criteria required by local preservation boards. To circumvent this issue, we are attempting to catalog and promote stories by linking local narratives to regional and national ones, to empower communities in the designation process.

Why does the landscape architecture profession have so few practitioners who are people of color?

I am actually less concerned with making the profession more diverse and would rather work to help transform the profession to make it more hospitable and comfortable for people of color—and that’s an important distinction. I’m reminded of the quote from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., via Harry Belafonte, “I’m afraid that I may be integrating my people into a burning house.” There are real problems with how we define, celebrate, and practice landscape architecture, specifically within communities of color, and that suggests that the foundational systems of landscape architecture require rethinking.

What, then, are the necessary structural reforms to rectify this lack of representation?

I think three major reforms are desperately needed. The first is on the issue of visibility, where organizations prioritize showcasing the work, thought, and contexts of practitioners of color. The diverse practitioners involved with the Landscape Architecture Foundation’s Olmsted Scholars Program is a good example of this kind of visibility. Another example is the firm Mithun, which has recently earned the JUST Label after undergoing an independent audit of its business practices and how they align with equity. Second, we need more faculty of color. Research suggests that students are more likely to pursue degree programs and graduate if they interact with teachers with whom they can identify. Third, we need to rethink our curricula and career aspirations in landscape architecture, including and elevating the experiences of people of color while accepting that not everyone in landscape architecture aspires to work at leading or mainstream firms. Many students of color wish to support their communities, and we need to prepare them to do so.

Could you elaborate on your call for a People’s History of Landscape Architecture to be formulated?

Well, although Howard Zinn’s book, A People’s History of the United States, has some issues—mainly that its zeal to overturn the then-exclusionary character of mainstream American history compromised some of its scholarship—it was quite a revelation in its time. It has inspired many others to revisit narrow framings of history and to ask why it doesn’t reflect “all of us”— the good, the bad, and the ugly. Landscape architecture is still in the “striver phase” (celebrating our potential, focusing on the highs and the “greats”), and that has made the profession’s history selective. But I believe this approach is out of touch with the global actors shaping the landscape, which is why I suggested A People’s History of Landscape Architecture; it’s an attempt to re-evaluate what we think we know about landscape architecture through those marginalized by that history…an attempt to reckon with challenges that aren’t often discussed, with the aim of making the profession more democratic.