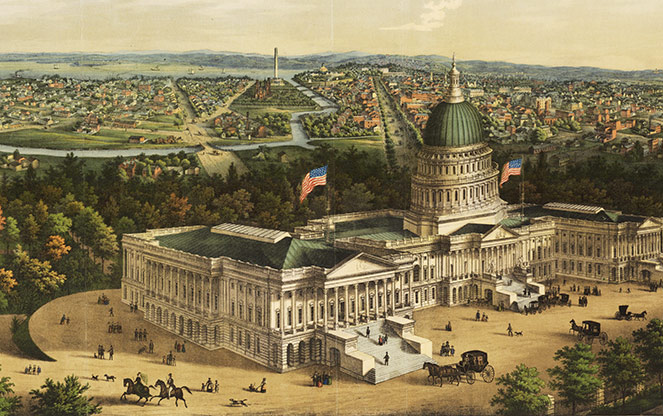

Panoramic View of Washington City. Image © E. Sachse and Co., 1852.

Panoramic View of Washington City. Image © E. Sachse and Co., 1852.

Established in 1790 on 100 square miles at the confluence of the Potomac and Anacostia Rivers, the location of the District of Columbia was selected by George Washington in 1791. Two major plans guided the City’s development – the first was developed by French engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant in 1791, and laid out the overall grid of streets and diagonal boulevards; the second, named for James McMillan who led a planning commission, was developed in 1901. The two plans continue to be the most consequential and evident design imprints on the nation’s capital.

From its beginnings to 1901

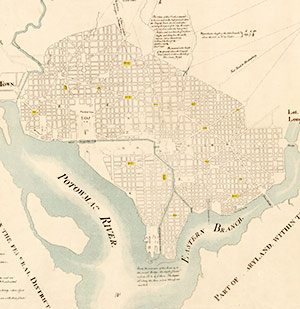

Carved from land donated by Maryland and Virginia and incorporating Georgetown and Alexandria, the boundaries of the District were marked by 40 stones set by surveyor Andrew Ellicott and freed African American astronomer Benjamin Banneker. Inspired by planning principles borrowed from Milan, Paris, and Amsterdam, in 1791 L’Enfant developed a Baroque work of art that would symbolize the ideals of democracy and the nation’s emerging status in the world—one of only two largely intact Colonial-era city plans in America today (Savannah, GA being the other).

Radiating from the Capitol and the White House, L’Enfant’s plan created a monumental core overlaid by a grid of streets and transected by wide diagonal avenues lined with trees, ornamented with sculpture, and visually connecting significant vistas. Where the orthogonal grid intersected the diagonal avenues, L’Enfant indicated fifteen parcels called reservations that would ensure the preservation of open space for public use, limit development, and serve as platforms for the display of monumental sculpture. A picturesque greensward extending from the Capitol to the White House was to be lined by federal buildings. Though L’Enfant was eventually dismissed from the project, Ellicott, the surveyor, redrew his plan from memory, revised it, and developed a plan for subsequent development, performing at both practical and ceremonial levels. Ellicott expanded L’Enfant’s designated open spaces and suggested the appropriation of seventeen reservations totaling 541 acres for federal use.

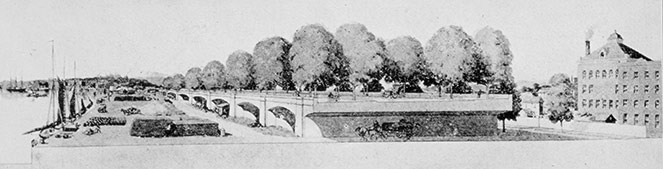

Piecemeal development of the District occurred through the next several decades with much of the planning of parks and streets dictated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Board of Public Works. The Potomac Flats that would become the Mall were malarial tidal swamps, Georgetown was used as dumping grounds, and the picturesque Rock Creek valley was an open sewer. In 1846, instigated by disagreements over slavery, the portion of D.C. granted by Virginia was returned to the Commonwealth, thus leaving the capital city solely on land contributed by Maryland. In 1851 landscape gardener Andrew Jackson Downing was commissioned to prepare designs for the National Mall, the Capitol grounds, and the White House. His treatment for the Mall, twenty years later criticized by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. as disorderly and confusing, included four distinct parks (only one was actually constructed) interconnected by curvilinear walks and drives. In 1874 Olmsted developed a densely wooded terrace to frame views of the Capitol from Union Square at the east end of the Mall, unifying the transition from the monumental statehouse to its park-like setting. Dredging of the Potomac to improve navigation resulted in the slow reclamation of more than 700 acres of land that would eventually form the western section of the Mall.

In 1867 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers proposed the development of the 1,000-acre Rock Creek Park, which was created by the Washington Board of Trade in 1890 and encompassed the 170-acre National Zoological Park, established a year previous. Later, the Board of Trade would battle with the Georgetown Citizen’s Association, which wanted to culvert Rock Creek and fill the valley to increase real estate. The argument was part of a larger conflict regarding administration of Georgetown, which had resulted in the renaming of its streets in 1895 to adhere to L’Enfant’s organization of the District.

Meanwhile, more than 700 miles away, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition was taking place in Chicago, designed primarily by Olmsted and architect Daniel Burnham. The event popularized the City Beautiful movement and the development of French-inspired Beaux Arts principles including axial organization, symmetrical and balanced design, and a sense of grandeur. Seven years after the Exposition and in commemoration of the District’s centennial, the American Institute of Architects held their annual convention in D.C. with an address by Olmsted who called for the employment of landscape architects in the planning of the District. Recognizing that L’Enfant’s plan was slowly being diminished, the convention resulted in a call for a resolution that would install a design commission to guide future growth of the District.

Rendered Section of Proposed Open Valley Treatment from McMillan Commission Report, 1902. Image © Library of Congress.

Rendered Section of Proposed Open Valley Treatment from McMillan Commission Report, 1902. Image © Library of Congress.

The McMillan Plan and the District’s Future

In 1901 the Senate Park Commission was assembled by James McMillan, comprised of Daniel Burnham, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., architect Charles McKim, and sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, all of whom had been involved with the Exposition in Chicago. These men (save Saint-Gaudens) spent seven weeks traveling throughout Virginia and Europe, visiting cities that would have been influential in the development of L’Enfant’s plan including Rome, London, Paris, Frankfurt, and Vienna. Le Nôtre’s designs at Versailles and Vaux-le-Vicomte were particularly influential for the Senate Park Commission’s designs for the Mall, which would provide a cruciform park-like setting flanked by carriage drives and punctuated with reflecting pools and memorials. Serving as the monumental core, the plan for the Mall called for the removal of a railroad terminal, the development of cultural and governmental buildings, and the razing of nearby slums.

Beyond the Mall and influenced by Olmsted Sr.’s design for his picturesque Emerald Necklace in Boston, the Commission developed designs for an interconnected system of parks where the city’s residents could enjoy the natural environment within the urban setting. The establishment of parkways along the Potomac River and Rock Creek as well as the creation of roads and bridges served to link landscaped parks, swimming facilities, and the District’s myriad neighborhoods.

Administration Building. Photo © Library of Congress.

In 1910 President Taft formed the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA), which would be responsible for developing the District’s City Beautiful plan. Comprised of many of the same individuals who had worked on the Senate Park Commission, the CFA would advise on the District-wide character and placement of monuments, buildings, fountains, sculpture, and their accompanying landscape treatment. The Commission’s influence was broad: they warned against the bisecting of D.C.’s circular parks with roads, commented on the design of lampposts and the selection of trees, and recommended the development of large open spaces including the transformation of Civil War forts into public parks. In 1916 land on 16th Street was set aside for the creation of Meridian Hill Park, designed by George Burnap, Horace Peaslee, and Ferruccio Vitale. In the 1920s Olmsted, Jr. and the American Society of Landscape Architects campaigned for the acquisition of a hilly site near the Anacostia River, providing the setting for the National Arboretum. In 1926 the National Capital Park and Planning Commission was formed and the Public Buildings Act passed the same year providing funds for the construction of the Federal Triangle on the south side of Pennsylvania Avenue between the White House and the Capitol. The pinnacle of Beaux Arts classicism in the District, the 70-acre Triangle was completed in 1937.

The Shipstead-Luce Act of 1930 extended the CFA’s regulatory influence into the private realm by advising on the design and construction of areas bordering property managed by the federal government including Rock Creek Park, land reserves, and the borderline of D.C. The 1930s witnessed funding by the Works Progress Administration for work on the Capitol walls and the eastern terminus of the Mall at Union Square, among many other projects. Led by Olmsted, Jr. who was advising on projects across the District at a salary that barely covered his living expenses, the Olmsted Brothers firm was instrumental in the design of the District’s most significant and iconic landscapes. Their designs for the Thomas Jefferson Memorial at the edge of the Tidal Basin and the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial on Analostan Island were inspired by work Olmsted, Sr. had completed for the Columbian Exposition’s Wooded Isle.

Reflective of trends across the country at this time, Modernist ideas began to drive development of the District’s landscape: Suburban expansion, decentralization of government buildings, the proliferation of automobile infrastructure, and federal art programs contributed to an evolving landscape for the nation’s capital. Accommodating the need for wartime infrastructure, wood and stucco “tempos” were erected along the Mall and a massive campus was proposed to be constructed at the base of the Memorial Bridge at Arlington National Cemetery. Under strong urging from the CFA, this construction—dubbed the Pentagon—was relocated to its present location, retaining the configuration it had been given in response to the shape and topography of its formerly recommended setting. The post-War years saw the birth of the historic preservation movement and the designation of the Old Georgetown Historic District. At the same time, significant components of Southwest D.C. were razed for urban renewal projects, largely designed by Chloethiel Woodard Smith and Dan Kiley. In the 1960s CFA members Hideo Sasaki and John Carl Warnecke worked with First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy on the development around Lafayette Square, which faces the White House, one that melded historic preservation and new construction. In 1959 Chairman of the National Capital Planning Commission Harland Bartholomew, addressing the growing need for public transportation, proposed a 33-mile rapid transit system. In 1968 a plan was approved to construct a 97-mile system (38 miles in D.C. with the remainder connecting to Maryland and Virginia locales), adopting Brutalism for the subterranean stations.

World War II Memorial, 2009. Photo © Charles A. Birnbaum.

World War II Memorial, 2009. Photo © Charles A. Birnbaum.

Under the leadership of the Pennsylvania Avenue Redevelopment Corporation, the 1970s witnessed the revitalization of Pennsylvania Avenue for parade viewing with the establishment of raised terraces, a shared cornice line for buildings, and the planting of clipped lindens. In addition to the Avenue, a diversity of ancillary spaces were developed at this time: Pershing Park designed in 1979 by M. Paul Friedberg; Freedom Plaza designed by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and George Patton; and the terraced John Marshall Park designed by Carol Johnson to front Old City Hall. Noteworthy projects by the firm Oehme, van Sweden include the planting redesign at Pershing Park, the design of the Federal Reserve Board in 1977, and the National World War II Memorial in 2004. Throughout this period, cultural institutions including many of the Smithsonian museums were constructed along the Mall and the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts was built overlooking the Potomac.

Through the latter part of the 20th century and into the new millennium, the District has continued to develop along the plans set forth by L’Enfant and the Senate Park Commission. Evolving philosophies of memorialization and increased security concerns have challenged the continued design of its landscape, yet these two plans have miraculously created a foundation from which all work happens within a common, symphonic design framework. With almost 7,500 acres of parkland and nearly 10,000 acres of National Park Service-managed property, the District is both a city for the American people and an international destination. We hope you will be inspired to explore the unique and unrivaled landscape legacy that is showcased in What’s Out There Washington, D.C.

“Washington, once known as the City of Magnificent Distances, may now be termed the City of Magnificent Possibilities. In spite of its century and a quarter of years, it is still a City of Beginnings. Nothing is completed. Everything is begun. It is a city of transitions.” – Charles Moore, 1922