Dabney Hill, a rural, self-sustaining African American community established by Daniel Dabney in 1887, is an outstanding example of a Texas Freedom Colony that still has an active, living community and whose historic vernacular landscape retains a legible community core despite suffering severe storm damage in recent years. Dabney Hill is representative of the challenges facing the remaining extant Freedom Colonies, which have seldom been recognized or protected as significant cultural landscapes.

History

Following the end of the Civil War, Black Americans in the South faced social, political, and economic oppression even after the enactment of Emancipation. To avoid becoming involved in the perilous conditions of sharecropping or debt bondage, some formerly enslaved people organized to accumulate land and form intentional, self-sustaining communities separate from white society. Many of these communities emerged throughout the South in the Reconstruction era, and in Texas, they became known as Freedom Colonies.

Children and medical staff at Clarksville Freedom Colony, Travis County, TX. Photo courtesy Austin History Center.

Children and medical staff at Clarksville Freedom Colony, Travis County, TX. Photo courtesy Austin History Center.

From 1865-1930, more than 550 Freedom Colonies were established across the state, mostly in the eastern corridor, where a majority of the state’s plantations and sharecropping estates were concentrated. Though rare, in a few cases plantation owners willed land to their Black descendants. Many Freedom Colonies were founded in flood-prone coastal areas or low-lying plains, where land vulnerable to severe weather events was cheaper, less populated, and therefore easier for African Americans to acquire by purchase or through adverse possession.

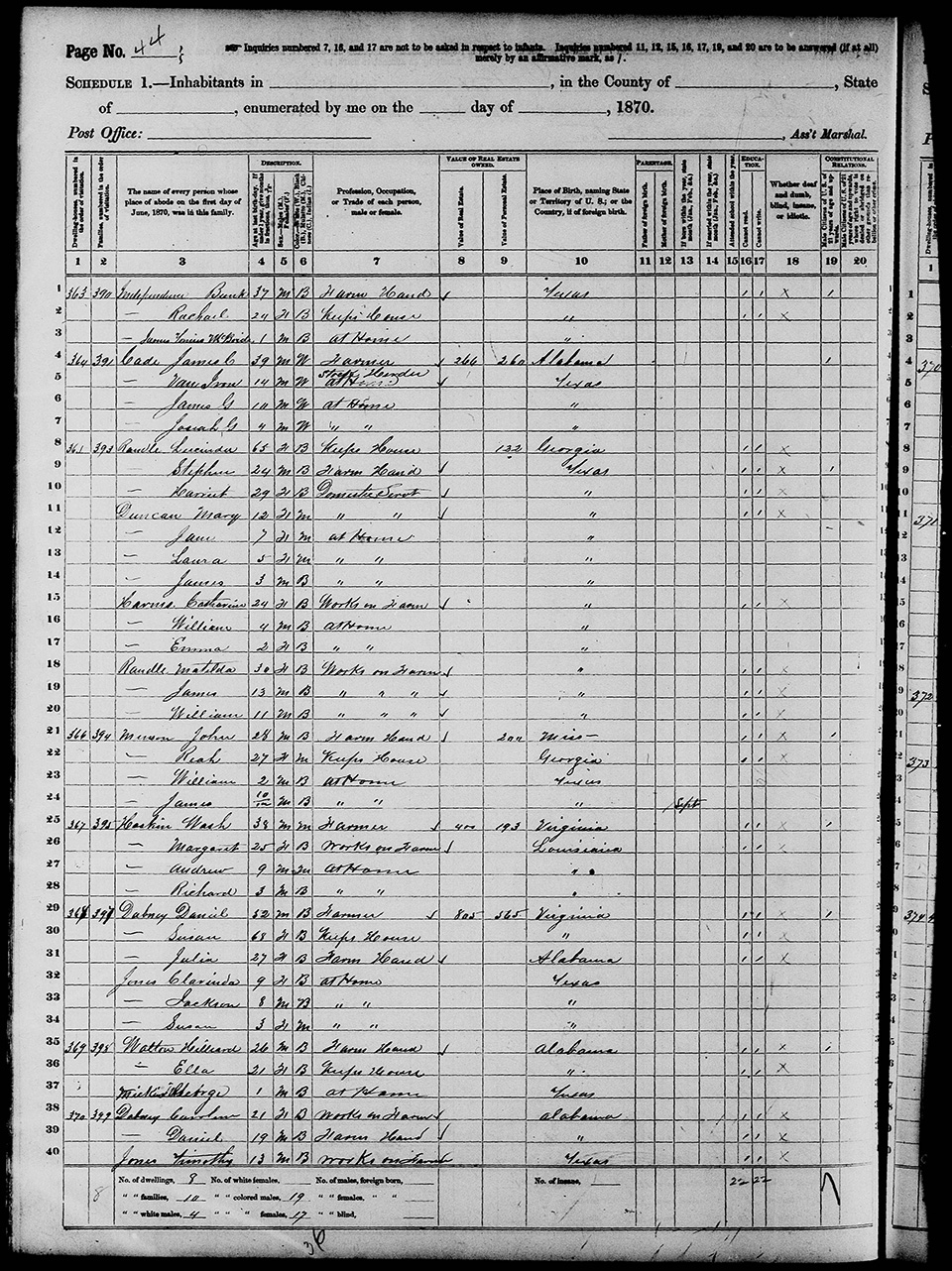

1870 Census document showing Daniel Dabney landholdings. Photo courtesy Gloria Smith.

1870 Census document showing Daniel Dabney landholdings. Photo courtesy Gloria Smith.

Dabney Hill, a Freedom Colony in Burleson County, was named for community founder Daniel Dabney, who owned the land on which the Dabney Hill Missionary Baptist Church was established in 1887. Covering approximately 50 acres, Dabney Hill is an outstanding example of a Freedom Colony that still has an active church congregation and whose historic vernacular landscape retains a legible community core of extant structures. The cultural landscape of Dabney Hill is representative of most Freedom Colonies: a rural, agrarian cluster of homesteads anchored by a church and cemetery, a Masonic Hall and a school (in Dabney Hill, the Jones School). The segregated Jones School drew Black students from Dabney Hill and from several nearby Freedom Colonies but was shuttered at the onset of integration and later demolished, though the ruins of the school gymnasium remain on the property. The area surrounding Dabney Hill features vegetation typical of central Texas, including mature oaks, sumac, milkweed, honeysuckle, clover, and Texas bluebonnet, and is home to many species of wild birds, including mourning doves and quail, and endangered species, including falcons.

The half-acre property of the Dabney Hill Missionary Baptist Church was host to many gatherings, formal and informal, serving the spiritual and social needs of the community. The Masonic Hall, Ethiopian Star Lodge #308 (also called Prince Hall), provided a gathering place and offered rest and shelter to visiting preachers and other Black travelers who were prevented from staying in area hotels by segregation and restrictive Jim Crow laws. Dabney Hill Missionary Baptist Church and the Masonic Hall remain in situ within this cultural landscape, though they have suffered damage and neglect in recent years. Some descendants maintain homes nearby, and the church is still home to an active congregation.

Dabney Hill Freedom Colony, Burleson County, TX. Photo by Owen Schwartzbard.

Dabney Hill Freedom Colony, Burleson County, TX. Photo by Owen Schwartzbard.

Many Freedom Colonies declined in population following World War II, when economic, social, and structural forces led to attrition and migration from rural Black communities. As Texas urbanized and densified, many major cities and suburbs absorbed or developed atop Freedom Colonies, erasing or obscuring their tangible legacy. Many Freedom Colonies’ descendants continue to sustain strong familial and social ties through dispersed but interconnected communities, reinforced by gatherings and reunions. Because many Freedom Colonies have been physically neglected, destroyed, or left behind, they have seldom been seen as whole cultural landscapes but rather as insignificant groupings of neglected buildings. It is exceptional that Dabney Hill and its institutions have endured, a living testament to the resilience of its founders and their descendants.

Threat

On March 18, 2018, a fierce storm hit Burleson County with winds gusting at 80mph and hail larger than baseballs. This storm collapsed the roof of the church sanctuary and endangered the bell tower, which was put in storage for potential reconstruction or reuse on-site. Further deterioration of the buildings that anchor the landscape, including the historic Masonic Hall, is easily foreseeable, especially the remains of the church, which continue to be open to the elements. Reforestation of the open spaces of the landscape is possible if maintenance slows or stops.

The Dabney Hill landscape now faces the threats of neglect and encroachment. The congregation is still active, but as it has lost members by attrition over the years, fewer dedicated people are left to care for the church and Masonic Hall property. The Masonic Hall has not been occupied in some time. Due to both limited funds and dwindling congregant numbers, consistent maintenance for the church and school grounds has become a challenge.

The threats of future hazardous climate events and development encroachment also pose risks to the site. Burleson County is prone to severe weather, including both draught and flooding (flash flooding and El Niño), and a large portion of the county is within the 100-year floodplain area. Snook, the incorporated town nearest to Dabney Hill, is located a mere twelve miles from the rapidly expanding twin cities of Bryan and College Station. A new subdivision has been built with the potential for expansion, and there are signs that developers are looking at acquiring land in Dabney Hill. Issues of Black land loss, especially in situations of heir property or unclear title, pose potential threats to the Dabney Hill landscape. Development pressure may not bring physical changes to the Dabney Hill landscape for a decade, but the potential for land ownership changes sealing that fate are foreseeable.

What You Can Do to Help

Donate to Preservation Texas with earmarked funds to support the repair of the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge in Dabney Hill. Supporters of Dabney Hill are in the process of applying for the Texas Rural African American Heritage Grant program, which awards up to $75,000 for projects such as the repair of the lodge. In order to be eligible, the applicants must provide a cash match of 25% of the total project cost up to $25,000. Any funds donated to Preservation Texas earmarked for the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge go directly toward the match of 25%.

Preservation Texas

c/o Dabney Hill Masonic Lodge Fund

P.O. Box 12832, Austin, TX 78711

Phone: (512) 472-0102

E: thompson@preservationtexas.org

Learn More about Dabney Hill by watching Discovering My Roots Down Home, a documentary featuring the story of Gloria Smith produced by The Texas Story Project and the Bullock Texas State History Museum.

Support the Texas Freedom Colonies Project to promote the work of mapping, archiving, and sustaining the living and remembered legacy of Freedom Colonies.