Since its founding nearly one hundred years before the Revolutionary War, New Rochelle, New York has undergone several transformations. Variously a colony for Huguenot refugees, a hotbed for abolitionist movements, a hub of European immigration, and a classic American suburb, New Rochelle’s diversity and proximity to New York City have induced physical as well as social changes. Urban renewal projects in the mid-twentieth century tore apart the community’s historic African American neighborhoods. Today, visionary residents and ambitious urban planning projects offer opportunities for equitably rebuilding this cultural landscape.

History

Often perceived as a classic American suburb, the historic town of New Rochelle in Westchester County, New York, pre-dates the Revolutionary War by a hundred years and has borne witness to great social, political, environmental, and developmental changes in the three centuries following. New Rochelle was unique among New York colonies for its founding by French Huguenot refugee families, alongside a relatively large population of enslaved African Americans. Thirty-three Protestant Huguenot families fleeing Catholic pogroms in La Rochelle, France, arrived in this region in 1688, purchasing land from John Pell, whose ancestor Thomas Pell had forcibly overtaken the land from the ownership of the Siwanoy Indians a few decades earlier.

Through the mid-eighteenth century, New Rochelle remained largely populated by French refugees. The first national census, conducted six years after the Revolutionary War in 1790, records a population in New Rochelle of 693 residents, of whom 136 were African American. Thomas Paine, the essayist and abolitionist (and perhaps the town’s most famous resident), settled in New Rochelle after the Revolutionary War, joining an existing population of abolitionist Quakers and one of the earliest and largest populations of free African Americans. By the 1820 census, the African American population in New Rochelle had increased slightly to 150. Though slavery was not abolished in New York State until 1820, notably, only six people were counted as being enslaved.

Following the Civil War, in which both Black and white soldiers from New Rochelle served the Union cause, the town completed its transition from a rural farming community into a sophisticated suburb and resort community with several glamorous hotels, gardens, and attractions luring wealthy white families to this and other neighboring New York City suburbs. Glen Island Resort, which featured bathing beaches, an exotic animal zoo, a natural history museum, and a miniature steam train, was considered America’s first summer resort, with annual attendance of nearly one million people by the turn of the twentieth century.

Over the next several decades, New Rochelle experienced large waves of immigration, especially of Jewish, Italian, and African American families seeking economic opportunities. Redlining and other forms of restrictive building and development codes excluded African Americans and some non-Protestant immigrant populations from living in New Rochelle’s luxurious waterfront villas or fashionable new suburban developments, but this did not prevent their communities from thriving.

Huguenot Street between Cedar and River streets, New Rochelle, 1960. Photo courtesy Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Huguenot Street between Cedar and River streets, New Rochelle, 1960. Photo courtesy Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Lincoln Avenue became the vibrant center of African American life in New Rochelle, supporting a lively commercial corridor of successful small businesses, surrounding residential streets of single-family homes, and the segregated Lincoln Elementary School. Several prominent African Americans, including Presidential Medal of Freedom recipient Whitney Young, Jr., actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, jazz musician Branford Marsalis, and Olympic athletes John Woodruff and Lou Jones, hailed from or settled in New Rochelle. In a landmark 1961 desegregation case, the first school desegregation case outside of the American South, the United States Supreme Court ruled that Lincoln Avenue School was unlawfully segregated, and it was subsequently closed and finally demolished in 1965.

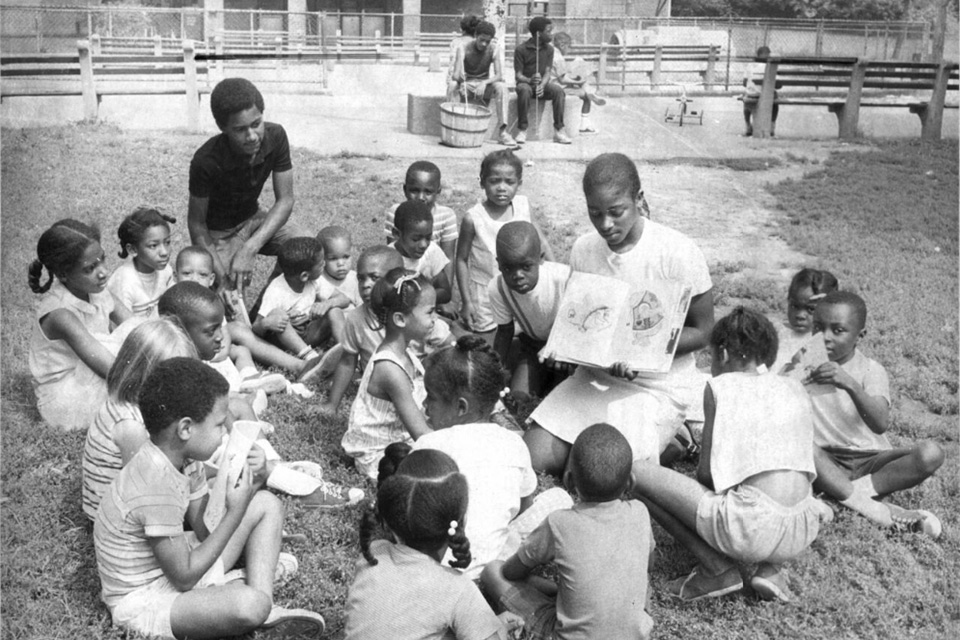

Children at New Rochelle Public Library storytime, 1960. Photo courtesy New Rochelle Public Library.

Children at New Rochelle Public Library storytime, 1960. Photo courtesy New Rochelle Public Library.

In the mid-twentieth century, urban renewal efforts swept through urban centers like New York and extended into smaller communities like New Rochelle. Robert Moses’ ambitious pursuit of constructing a massive New England thru-highway began in earnest in 1951, with Interstate 95 built in 1957 to connect New York City with surrounding towns. As was the case with many American cities, the construction plan for Interstate 95 tore through the African American neighborhoods of New Rochelle, leading to the displacement of families, many of whom had roots in the community for several generations, and the closure of many businesses within the Lincoln Avenue corridor.

Site cleared for new construction, New Rochelle, 1963. Photo courtesy Dominic Bruzzes Collection and Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Site cleared for new construction, New Rochelle, 1963. Photo courtesy Dominic Bruzzes Collection and Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Memorial Highway, originally designed to connect Interstate 95 with two other regional parkways, was only partially completed, necessitating a complex matrix of roadway solutions to be built to direct its intended traffic. The tangle of resulting roadways disconnected the historic Lincoln Avenue community and created unsafe conditions for pedestrians. By the 1960s, desegregation and urban renewal efforts had already spurred many white residents to leave New Rochelle for some of the nearby wealthier, whiter towns of Westchester County, creating a geographic, demographic, and economic divide that has persisted for decades.

Interstate construction, New Rochelle, 1960s. Photo courtesy Dominic Bruzzes Collection and Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Interstate construction, New Rochelle, 1960s. Photo courtesy Dominic Bruzzes Collection and Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Today, Black neighborhoods that were splintered around Memorial Highway are urban palimpsests with layers of erasure, resettlement, and redevelopment. Understanding, recording, and visualizing these invisible layers of cultural history and heritage—both spatially and temporally—fortifies residents, city leaders, and designers in efforts to chart an equitable vision for new developments. New Rochelle is the recipient of a large New York State grant under its Downtown Revitalization Initiative (DRI) to fund traffic studies and planning and development projects to connect the Lincoln Avenue Corridor to the massive re-development occurring downtown, on the other side of Memorial Highway. In addition, the city is engaging community participation in its plans to re-route traffic and convert sections of Memorial Highway to public space in the form of a linear park, called The LINC, which would showcase African American culture, art, and history. However, the re-zoning of the area and private development incentives will also have a profound effect on the community, and community engagement on re-zoning initiatives is superficial.

Threat

New Rochelle is growing and changing in significant ways: there are currently more than 30 downtown development projects and a large transportation improvement planning initiative underway. Accelerated urban change initiated without meaningful community input brings unintended consequences to historically disadvantaged populations that have already disproportionately experienced its long term negative and traumatic effects. In New Rochelle, these populations are concentrated in the West End, the Hollow, and the Lincoln Avenue Corridor, which will be directly affected by impending zoning and land use developments in conjunction with the LINC project. Many residents of these communities are renters, and they rely on affordable small businesses and shared low-cost community resources (like laundromats). The DRI is a transit-oriented scheme that envisions the future of New Rochelle as a community of commuters to New York City aims to attract young, high-earning urban dwellers to the suburbs. Five years into the scheme, several luxury rental development projects are under construction. New, more expensive housing developments drive up rent prices and encourage higher-cost grocery stores, shops, and restaurants to move into the community to meet the demands of high-earning residents.

This new vision for the city is negatively impacting the African American community (20% of New Rochelle’s population of 78,000) through endangerment of the local economy that circulates Black dollars within the Black community; disruption of local, regional, and national food distribution networks; displacement and gentrification of neighborhoods; inequitable access to schools and educational systems; and lack of focused consideration and acknowledgement of the cultural history of the community. In order to ensure native residents receive the full benefits of the city’s vision for development, community members must be integrated into the planning process.

In 2021, a group of students from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design collaborated with New Rochelle community members to explore ways of integrating cultural heritage in future public infrastructure schemes. Their work highlighted the depth of knowledge and expertise within the community and the ability of planning practitioners to utilize and foreground community insight.

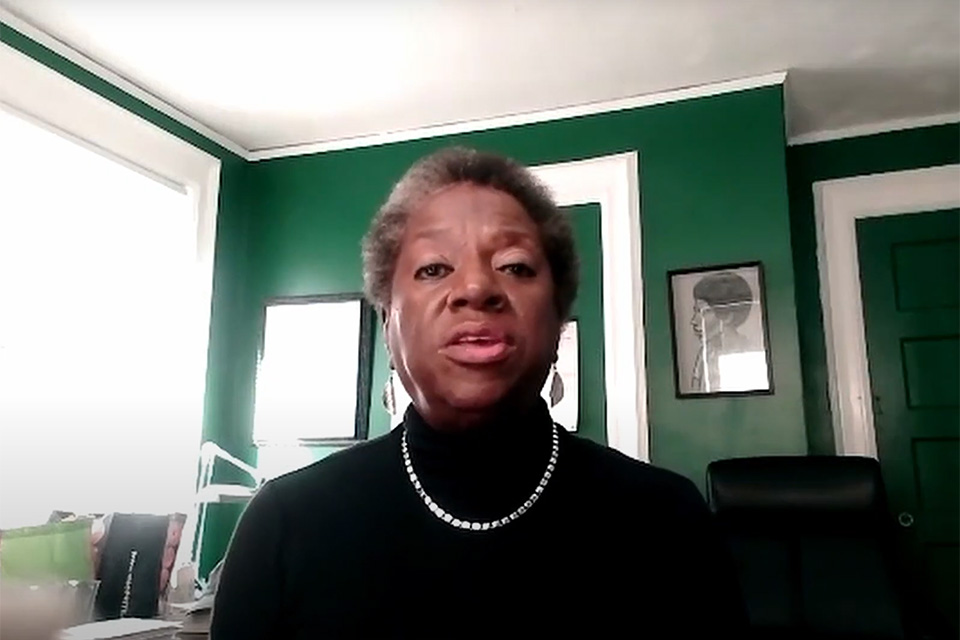

(left) Photo courtesy Lincoln Park Conservancy.

What You Can Do to Help

In November 2021, Senator Charles Schumer and Representative Jamaal Bowman worked with Lincoln Avenue community members and organizations to secure $11,960,000 for the City of New Rochelle LINC: Safety, Mobility, and Economic Opportunity project. With this funding, the city hopes to redirect roadways to be safer, more accessible, and more friendly to pedestrian and cyclists. In addition, the city intends to create new public green space with historic interpretation honoring the historic Lincoln Avenue Corridor community.

Write to Senator Schumer and Representative Bowman and urge them to responsibly allocate funding to ensure that New Rochelle’s local residents are not driven out by new urban development. Encourage them to continue collaborating with Lincoln Avenue residents to implement community-based solutions.

322 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510

Phone: (202) 224-6542

E: https://www.schumer.senate.gov/contact/email-chuck

1605 Longworth House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515

Phone: (202) 225-2464

E: https://bowman.house.gov/send-an-email

Support local community organizations working to preserve and promote sustainable, equitable infrastructure, public space, and cultural enrichment and education including: Grow! Lincoln Park Community Garden, The Lincoln Park Conservancy, Inc., New Rochelle Municipal Housing Authority, and New Rochelle Community Action Program.

Grow! Lincoln Park Community Garden

Phone: (919) 224-4243

E: growlpcg@gmail.com

T: @growlincolnpark

F: http://www.facebook.com/growlincolnpark

The Lincoln Park Conservancy, Inc.

177A East Main Street #341, New Rochelle, NY 10801

Phone: (914) 224-4243

E: thelincolnparkconservancy@gmail.com

T: @the_conservancy

F: www.facebook.com/thelincolnparkconservancy

GoFundMe: https://gofund.me/d032d716

New Rochelle Municipal Housing Authority

50 Sickles Avenue, New Rochelle, NY 10801

Phone: (914) 636-7050

E: afarrish@nrmha.org

New Rochelle Community Action Program

95 Lincoln Avenue, New Rochelle, NY 10801

Phone: (914) 636-3050

E: http://www.westcopny.org/community-action-partnerships-2/

Provide Feedback to the city of New Rochelle about the proposed downtown revitalization and LINC projects through their virtual reality visualizer tool. This tool allows members of the public to envision proposed changes to the landscape around Memorial Highway—including proposals for increased green space and improved pedestrian links—by exploring the area using virtual reality technology. Offer feedback to support the proposed Lincoln Community Connector, which interprets the history of Lincoln Avenue and Memorial Highway through its urban fabric.

-

Photo courtesy Lincoln Park Conservancy.