Lindsay Heights, a historic African American neighborhood in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, has been a center of the city’s Black community for more than 150 years. The era of urban renewal in Milwaukee eviscerated the community, and demolition was followed by decades of disinvestment. Yet community members have employed grassroots strategies to turn vacant lots and buildings into urban gardens and green business incubators. Resident-led initiatives continue to draw on the history of this neighborhood to transform a post-urban renewal landscape of blight and neglect into a vibrant, verdant, resilient community anchored by gardens, public green space, and rich cultural traditions.

History

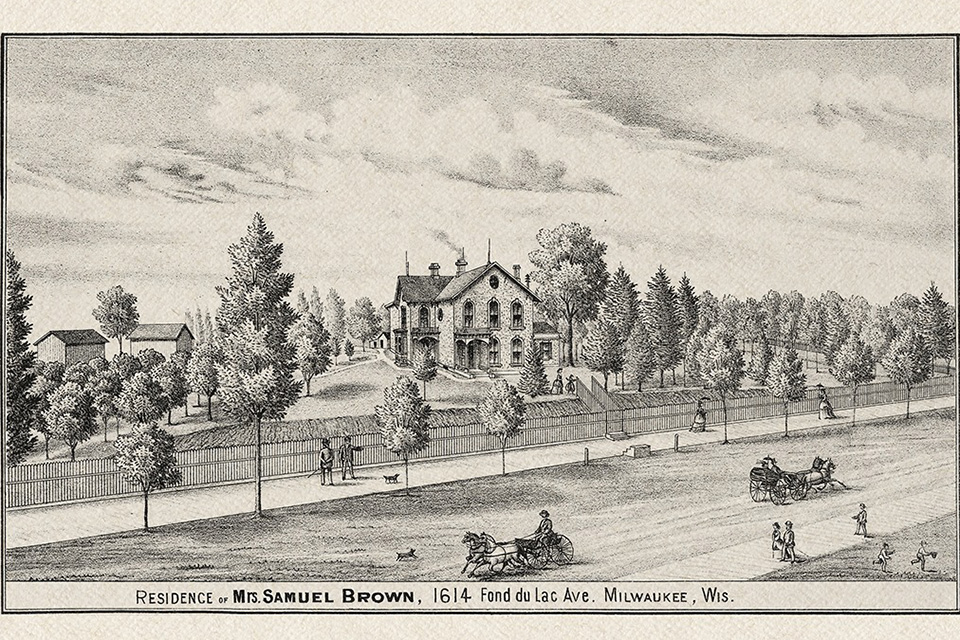

Lindsay Heights, a historic African American neighborhood in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, has been a center of the city’s Black community for more than 150 years. The area was first an agrarian settlement populated by several large farms, including one owned by politician and abolitionist Samuel Brown. In 1842, sixteen-year-old Caroline Quarlls escaped enslavement on a plantation in St. Louis and sought shelter at Samuel Brown’s farm before venturing to freedom in Canada, becoming the first documented person to pass through this stop on what would become known as the Underground Railroad. Between 1842 and 1861, more than 100 enslaved people travelled to Canada through Wisconsin.

Residence of Mrs. Samuel Brown, 1876. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society.

Residence of Mrs. Samuel Brown, 1876. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, this area was mostly home to Russian, Polish, and Jewish immigrants, and the culinary culture of this community remains influenced by this chapter of its history. The demographics of the region changed, however, as African Americans began to move into northern cities during the Great Migration. The area where they settled became known as “Bronzeville.” First used in the 1930s by an editor of the Chicago Bee to describe that city’s African American neighborhoods, the term was later popularized by the Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper with national readership. Milwaukee’s Bronzeville quickly became a hub of African American culture, with a bustling commercial corridor and a vibrant entertainment sector which produced and attracted musicians, artists, and writers. Nationally known artists including Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Billie Holiday drew large crowds of both Black and white Milwaukee residents to Bronzeville’s jazz clubs on the weekends.

Walnut Street, Bronzeville, 1950s. Photo courtesy Urban Milwaukee.

Walnut Street, Bronzeville, 1950s. Photo courtesy Urban Milwaukee.

As Bronzeville prospered and grew, many Black professionals and business owners settled in an adjacent area that would later be known as Lindsay Heights. The community, comprising about 30 blocks just west of Bronzeville, bordered by Locust and Walnut Streets to the north and south and 12th and 20th Streets to the east and west, was an idyllic residential enclave with tight-knit neighbors, thriving businesses, and spacious homes in Victorian, Queen Anne, and American Foursquare styles.

In the mid-1960s, the construction of Interstate 43 and the planned Park West Freeway dissected the community, destroying numerous homes and businesses in and west of Bronzeville and dramatically transforming this urban landscape. Around the same time Milwaukee’s urban renewal program, ostensibly designed to improve housing in the city center, forced many residents to vacate or sell their property. On or near Walnut Street, more than 8,000 homes and businesses were lost. In 1969, plans for the Park West Freeway were abandoned, even after hundreds of homes had been destroyed to pave its way. In the decades following, remaining residents continued to foster a strong community identity despite civic negligence. Several vacant lots were transformed into parks and garden spaces, reinvigorating the landscape with open community green space and urban agriculture programs.

Alice’s Garden Urban Farm, Lindsay Heights. Photo by Pat Robinson (2021).

Alice’s Garden Urban Farm, Lindsay Heights. Photo by Pat Robinson (2021).

In 1972, a garden was established at 21st Street and Garfield Street and later named for Alice Meade-Taylor, a longtime community development advocate in Milwaukee. Alice’s Garden celebrates the community’s roots in agriculture and Black enterprise, offering education on regenerative farming, and preserving the neighborhood’s culinary, artistic, and cultural traditions. In the 2.2-acre garden, urban farmers and community members care for abundant rows of seasonal vegetables and cut flowers, while maintaining part of the site as open green space for community gathering. In the 1980s, a vacant space of slightly more than eleven acres near the historic Underground Railroad site and adjacent to Alice’s Garden, where several homes had been razed, was converted into a park named for Clarence and Cleopatra Johnson, prominent African American community members of the early twentieth century. In 1995, a historic marker was added by the Milwaukee County Historical Society signifying the site’s history as a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Johnsons Park, an open green space with multiuse athletic fields bisected by accessible walking paths, owned and managed by Milwaukee County Parks, was listed in a 2002 report by Milwaukee-based policy research group Public Policy Forum as one of the most-neglected parks in Wisconsin. Following the publishing of this report, the Johnsons Park Initiative was formed in partnership with the City of Milwaukee, Preserve Our Parks, Walnut Way Conservation Corps, and others to revitalize the park and surrounding community and maintain Alice’s Garden, the adjacent Brown Street Academy playground, and Johnsons Park.

In the 1990s, the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority began rebuilding homes in the neighborhood west of Bronzeville, which was officially designated Lindsay Heights in honor of community activist Bernice Lindsay in 1997. Since then, efforts to create and cultivate public green space and increase home ownership opportunities in Lindsay Heights have been led by its residents. Walnut Way Conservation Corporation was founded in the late 1990s by community residents Sharon and Larry Adams with goals of improving food security and revitalizing vacant lots by planting orchards and vegetable gardens, restoring dilapidated homes and creating pathways to home ownership, and providing community wellness programs for residents of all ages. In 2020, the Adamses opened Adams Garden Park, a multi-use office and convening space and community garden, to cultivate economic opportunities within the community, centered on deepening connections to craftsmanship, environmental stewardship, and preservation of cultural heritage.

Neighborhood fest, Lindsay Heights, 1982. Photo courtesy Milwaukee Public Library.

Neighborhood fest, Lindsay Heights, 1982. Photo courtesy Milwaukee Public Library.

Resident-led initiatives continue to draw on the history of this neighborhood to transform a post-urban renewal landscape of blight and neglect into a vibrant, verdant, resilient community anchored by communal gardens, public green space, and rich cultural traditions.

Milwaukee Fair Housing Demonstration, 1967. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society.

Threat

The Lindsay Heights neighborhood is at a turning point. The era of urban renewal in Milwaukee eviscerated the community. The demolition was followed by decades of disinvestment. Yet community residents have employed grassroots strategies to turn vacant lots and buildings into urban gardens and green business incubators. This community understands the economic and cultural value of maintaining tangible ties to its history but has not historically had the financial capacity to consider long-term preservation strategies.

At the same time, economic developed rooted in downtown Milwaukee - as seen in the 2018 opening of the Fiserv Forum sporting arena - is beginning to push north to neighborhoods like Lindsay Heights. There is real concern that the tangible legacy of Black prosperity, creativity, and community in this neighborhood will be further erased.

In November 2021, the Milwaukee Common Council adopted a new Fond du Lac and North Area Plan to address long-term development needs and opportunities in several neighborhoods including Lindsay Heights. Milwaukee’s Department of City Development consulted with community groups, including Walnut Way Conservation Corps, to devise the land-use policy recommendations and provisions for redevelopment outlined in the plan. As the plan is implemented in the coming years, it is essential that residents continue to remain involved in decision-making.

(Left Photo ) Milwaukee Fair Housing Demonstration, 1967. Photo courtesy Wisconsin Historical Society.

What You Can Do to Help

Write to Milwaukee County Parks and encourage sustained support for Johnsons Park and increased public information about the history of Lindsay Heights and the Underground Railroad in Milwaukee.

Milwaukee County Parks HQ

9480 W Watertown Plank Rd, Wauwatosa, WI 53226

Phone: (414) 257-7275

Contact Milwaukee Alderman Russell W. Stamper and encourage him to engage with Lindsay Heights residents as the Fond du Lac and North Area Plan is implemented and to discourage future developments pushing into the neighborhood’s historic cultural landscape.

District 15 Alderman Russell W. Stamper

City Hall

200 E. Wells Street, Room 205, Milwaukee, WI 53202

Phone: (414) 286-2221

E: Russell.stamper@milwaukee.gov

Donate to support the work of the Walnut Way Conservation Corps, Alice’s Garden, and Adams Garden Park.

Walnut Way Conservation Corps

2240 N. 17th Street, Milwaukee, WI 53205

Phone: (414) 264-2326

E: info@walnutway.org

Alice’s Garden

4000 N. 40th Street, Milwaukee, WI 53216

Venice R. Williams, Executive Director

Phone: (414) 687-0122

E: venicewb@gmail.com

Adams Garden Park

1836 West Fond du Lac Avenue, Milwaukee, WI 53205

E: sharon@hn-dev.com

Visit Lindsay Heights and the nearby Wisconsin Black Historical Society to more deeply engage with the Milwaukee’s African American history.

Wisconsin Black Historical Society/ Museum

2620 West Center Street, Milwaukee, WI 53206

Phone: (414) 372-7677