Introduction Overview

Landslide 2022: The Olmsted Design Legacy is a capstone event in a year of programming by The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) honoring the bicentennial of the birth of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. (1822-1903), the father of landscape architecture. It features twelve North American entries representing landscapes planned and designed by Olmsted, Sr., and his successor firms that now face multiple threats including inappropriate change or even erasure.

From neighborhood parks, including Andrew Jackson Downing Park, Newburgh, N.Y. and Washington Park, Milwaukee, WI, to expansive park and boulevard systems, such as that in Seattle, WA, and the State Parks System in California, the diverse group of landscapes featured in this thematic report range in size, scale, typology, and location and collectively represent the versatility and enduring vision of the Olmsted firm.

Olmsted, Sr., was shaped by his early experiences as a journalist, a career which led him to travel through Europe, Asia, and the American South, and as a farmer. He developed and disseminated a philosophy on the societal benefits of equal public access to parks, natural scenery, and open space as well as the protection of natural resources and the civic duty of park stewardship.

Andrew Jackson Downing Memorial Park, Newburgh, New York, 2022. Photo by Barrett Doherty.

Andrew Jackson Downing Memorial Park, Newburgh, New York, 2022. Photo by Barrett Doherty.

Olmsted, Sr.’s, remarkable forty-year career as a landscape architect began with the innovative entry in 1857, together with architect Calvert Vaux, for the award-winning “Greensward” plan for New York City’s Central Park. In realizing this ambitious concept, with all its multifaceted political, social, and economic implications, Olmsted and Vaux evolved landscape architecture from it origins in landscape gardening to a profession specializing in comprehensive systems-based design, essential to the development of urban and suburban environments for living and working. In 1887, Olmsted and Vaux collaborated for their last time, to design Andrew Jackson Downing Memorial Park with the assistance of their sons – the only such undertaking for these two generations of designers.

Following the successful completion of his design for Central Park, between 1879 to 1892 Olmsted, Sr., designed an interconnected park and parkway system in Boston. Known as the “Emerald Necklace,” this park network and its constituent boulevards and parks, including the 526-acre Franklin Park. This grand civic gesture catalyzed the establishment of metropolitan park boards and park and parkway systems across the country—including in Milwaukee, WI, Rochester, N.Y., Providence, R.I., Seattle, WA, and elsewhere —with Olmsted, Sr., and his successor firms hired as consultants, often working for decades to truly shape cities.

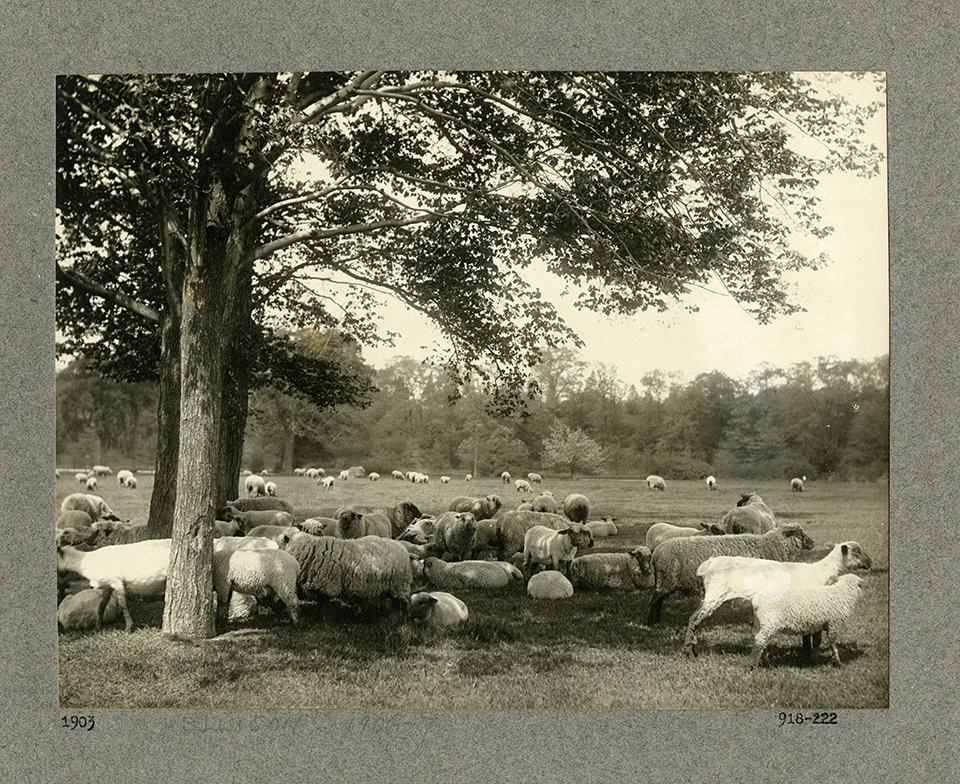

Franklin Park, Boston, Massachusetts, 1903. Image courtesy of Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Franklin Park, Boston, Massachusetts, 1903. Image courtesy of Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Olmsted, Sr.’s, experiences managing a gold mine in the Sierra Nevada motivated his efforts to preserve extraordinary natural features such as Yosemite and Niagara Falls by initiating the movement to create public scenic reservations. His firm also worked extensively in the private realm, creating residential communities, such as Druid Hills in Atlanta, GA, the only community on which all three Olmsteds – Olmsted, Sr., his son Olmsted, Jr. (1870-1957), and his nephew and stepson John Charles Olmsted (1852-1920) – worked. They also designed large and small estates, including the Coe Estate (Planting Fields), on Long Island. All their efforts were predicated on a sensitivity to natural conditions, with ample consideration given to greater community benefits while meeting clients’ needs.

Following Olmsted, Sr.’s, death in 1903, the firm he founded was led into the next half-century by John Charles Olmsted and Olmsted, Jr., with the appellation “Olmsted Brothers.” During this era, the firm was confronted with a different set of circumstances—including Westward expansion, the Great Depression, and the onset of two World Wars—than those encountered in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. With a talented roster of employees, Olmsted Brothers diversified its practice while maintaining loyalty to its founding principles. Olmsted, Jr., carried on the firm’s pioneering efforts to establish state parks around the country, playing a principal role in the creation of the nation’s first state parks system in California, and shaped the landscape of the nation's capital through his work on the McMillan Commission and beyond, including designs for the grounds of the Washington Monument and the Washington National Cathedral. Olmsted, Jr., and John Charles Olmsted expanded the firm’s practice to include the design of suburbs and regional plans, traveling constantly throughout the year to visit prospective developments across the United States and Canada, like Calgary, Alberta’s Sunalta Addition, and the City of Lake Wales, FL.

Sue-Meg State Park, California, 2022 © California State Parks, Brian Baer.

Sue-Meg State Park, California, 2022 © California State Parks, Brian Baer.

In the postwar era, confiscation of parkland for road construction, shifts in recreational trends, deferred maintenance, and an overall lack of appreciation for the historic design intent and Olmsted design legacy resulted in accrued neglect, partial loss and/or alteration of parkland, and even total erasure. A renaissance of Olmsted scholarship and advocacy followed in the 1960s, reviving interest in studying and protecting the firm’s body of work. While more than 200 Olmsted-designed landscapes are now listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and nearly three dozen are designated as National Historic Landmarks, countless others await rediscovery and revitalization. The threats today are varied and significant: a lack of valuation and protection; the impacts of climate change (drought, wildfires, invasive plants, pests, etc.); the loss of connectivity and porous edges with contiguous neighborhoods; and others. When taken together these threats pose additional challenges to stewards, including state and municipal governments, non-profit and grassroots group, and community stakeholders. As explored in this report, this matrix of threats reflects the current state of park and open space stewardship more broadly and invites a contemporary application of the philosophy and design intent of the Olmsted firm.

Although the Olmsted design legacy faces significant challenges, there is good news—the public’s love of Olmsted designed landscapes continues to grow, and there is time and opportunity to act. This year, the bicentennial of Olmsted’s birth, we echo the plea he made for Yosemite in 1865, that “this duty of preservation” is an imperative “because the millions who are hereafter to benefit . . . and the largest interest should be first and most strenuously guarded.” The intent of Landslide 2022 is to foster greater awareness and curiosity about the scope, scale, and richness of the Olmsted landscape legacy, and to encourage a stronger shared responsibility for its future.

Planting Fields Arboretum State Historic Park, Oyster Bay, New York, 2022. Photo by David Almeida.

Planting Fields Arboretum State Historic Park, Oyster Bay, New York, 2022. Photo by David Almeida.