The only project in the United States for which two generations of both the Olmsted and Vaux families collaborated, Downing Park honors the influential designer, horticulturalist, and author Andrew Jackson Downing. Underfunded for decades, the park is now under consideration to become the home of reinterred remains from a nearby nineteenth century African American burial ground. The convergence of the park’s diminished condition and the proposed commemorative landscape offers an extraordinary opportunity for stakeholders to come together to honor the reinterred individuals, while also advancing the park’s long overdue revitalization.

History

Born in Newburgh, New York, in 1815, influential designer, horticulturalist, and author Andrew Jackson Downing advocated for the creation of public parks in America and popularized landscape gardening among the nation’s growing middle and upper-middle classes. Downing’s writings greatly influenced both Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., and Calvert Vaux, who ultimately immigrated to the United States in 1850 to join Downing’s practice. The two collaborated until 1852, when, at the age of 36, Downing perished in a steamboat accident on the Hudson River.

Five years later, in 1857, Vaux invited Olmsted to join him in preparing what would eventually be the winning plan for the Central Park Competition. The two worked together until dissolving their partnership in 1879, though they later reunited to collaborate on Niagara Falls in 1885 and, lastly, in Newburgh, where they worked pro-bono beginning in 1887 on a commission to honor Downing.

Despite Downing’s prodigious impact, his home city had neglected, in the opinion of his family and friends, to adequately commemorate his legacy. In 1887 when Newburgh mayor Benjamin Odell proposed the creation of a public park, Downing’s widow, Caroline Downing Monell, and others, suggested naming it in Andrew Jackson Downing’s honor. She enlisted Vaux and Olmsted, Sr., to advocate on behalf of her suggestion.

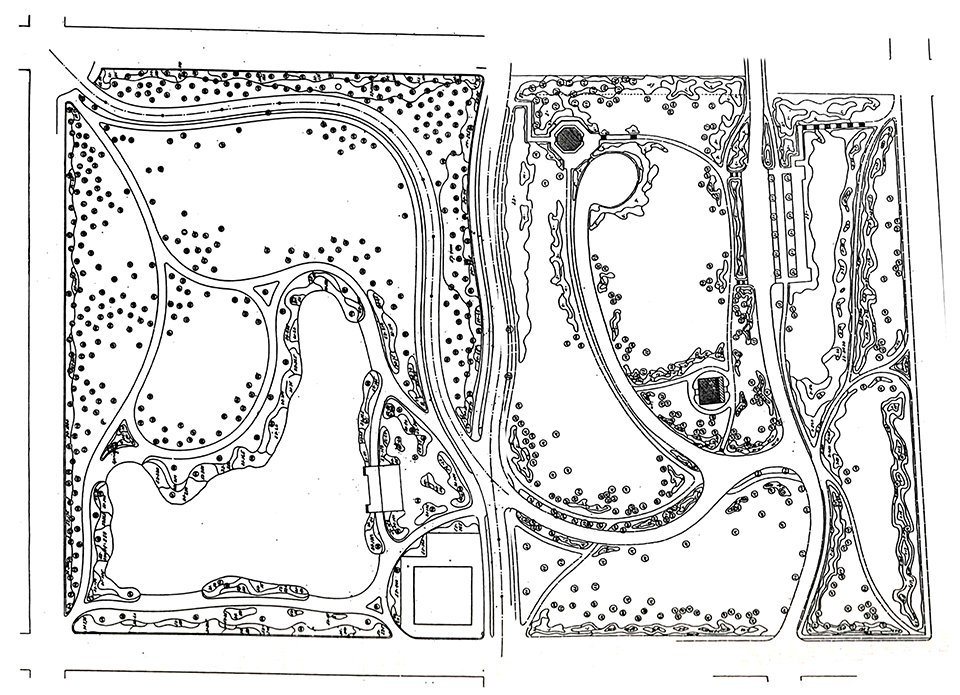

Downing Park Planting Plan, No. 23 and No. 18, 1895. Images courtesy of Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Downing Park Planting Plan, No. 23 and No. 18, 1895. Images courtesy of Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

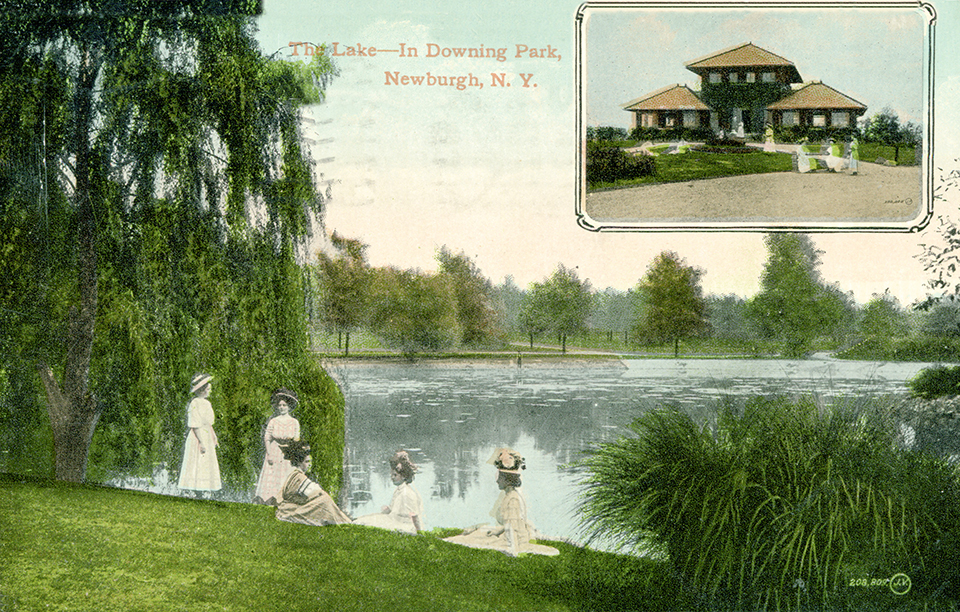

The city of Newburgh set aside a 25-acre, centrally located site for the park, which Olmsted, Sr., and Vaux visited in 1889. While the parcel offered broad, sweeping views of the Hudson River and the neighboring Hudson Highlands, the land was, as Olmsted, Sr., argued, too steep to accommodate pastoral features. The designers noted that the adjacent western plot, owned by the Water Board, was “of precisely the character needed” and inquired if they could incorporate it. Awaiting a response, Olmsted, Sr., and Vaux proceeded with preliminary studies of the site. Calvert Vaux and his son Downing Vaux (named, like the planned park, after his father’s mentor) planned the hilly eastern section while Olmsted, Sr., and his stepson, John Charles Olmsted, tackled the gentler area still owned by the Water Board. The designers integrated their respective designs, with Olmsted, Sr.’s, firm drafting the preliminary plan. The city, initially slow to advance the project, was hastened by the economic panic of 1893 and the need to create jobs. In early 1894 the Water Board surrendered land to the Park Commission and the designers were able to continue. With the elder landscape architects unable to work, John Charles Olmsted and Downing Vaux finalized the plans and superintended construction, which began in July of 1894. The 35-acre park opened on July 4, 1897, with many Picturesque elements: a great lawn, a significant water feature (Polly Pond), scenic woodlands, meandering walks, meadows, and a brick observatory. Designed by Downing Vaux, the observatory crowned the highest point in the park, affording visitors views of A.J. Downing’s beloved Hudson River. While neither the observatory nor the bandshell erected in 1905 survive, many of the original trees, the planting of which were guided by Warren Manning, superintendent of planting in the Olmsted office, still stand.

Postcard of Andrew Jackson Downing Memorial Park, Newburgh, New York. Image courtesy of Newburgh History Blog.

Postcard of Andrew Jackson Downing Memorial Park, Newburgh, New York. Image courtesy of Newburgh History Blog.

During the first half of the twentieth century, several structures and monuments were erected within the park. In 1908 a concrete pergola, designed by Frank Estabrook, was built on the foundation of a former farmhouse. A Volunteer Fireman’s Memorial was added to the park in 1910 and by 1920 a flagpole was inserted near the former site of Vaux’s observatory. In 1934 a shelter house was constructed on the eastern shore of Polly Pond. Designed by local architect Gordon Marvel, the structure was placed at the approximate location where Olmsted, Sr., and Calvert Vaux had hoped to situate a boathouse. A Civil War monument was dedicated that same year, and in 1946 an amphitheater was installed.

Postcard of Andrew Jackson Downing Memorial Park, Newburgh, New York. Image courtesy of Newburgh History Blog.

Postcard of Andrew Jackson Downing Memorial Park, Newburgh, New York. Image courtesy of Newburgh History Blog.

In the 1960s the construction of the South Street artery along the northern edge of the park altered topography and portions of the path system laid out by the original designers. The City Parks Department was eliminated by budget cuts leaving only the Department of Public Works to maintain the park. Additionally, expenditures for much-needed social services led to a lack of funding for park staff and maintenance. In 1987 a grassroots community group, The Downing Park Planning Committee (DPPC), was established to revitalize the park and contracted Landscapes, Inc. (now Heritage Landscapes) to create a Comprehensive Master Plan in 1989. The plan was accompanied by a document outlining the history of the park prepared by scholar and Newburgh native, David Schuyler. The well-received master plan was funded by the New York State Council for the Arts and resulted in more than $300,000 for park planning and improvements in the late 1990s, including the dredging of Poly Pond, revitalization of paths, installation of new benches and lighting, and renovation of the Shelter House, which was converted into a visitor center. A café opened in the Shelter House in 2018.

Photo by Barrett Doherty.

Threat

Downing Park is the only collaboration between two generations of Olmsteds (Frederick, Sr., and stepson John Charles) and Vauxs (Calvert and son Downing) as well as the final collaborative project of the two elder designers. Despite its national significance, the neighborhood park suffers from longstanding neglect. The City of Newburgh has not reinstated a Parks Department and only provides bare-minimum maintenance services, including trash removal and mowing, leaving the DPPC as primary steward. Despite their efforts, the organization has been unable to adequately address the myriad problems that plague the park. Accrued neglect has led to the deterioration of park structures and infrastructure: light fixtures are broken; paths are cracked and heaved from tree roots; and the pavilion is crumbling and riddled with graffiti. Aged trees pose a safety threat and need to be maintained, and the park overall is in need of greater vegetation management and renewal. More recently, it appears that the city is dumping building material in the upper, northeastern section of the park at the terminus of the park drive. The park, habitually used for illicit activities, has drawn comparisons to the conditions of Olmsted and Vaux’s Central Park in the 1960s and ‘70s.

In the early 21st century, the remains of more than 100 African American individuals were uncovered at the site of a public building project less than a mile from the park. The remains were excavated and transferred to a facility at SUNY New Paltz, where they have been stored ever since. In May 2022, the Newburgh City Council approved a resolution to reinter the remains in Downing Park, southeast of the highest point of the park, near the location once occupied by Downing Vaux’s observatory. The city issued a Request For Proposals (RFP) for a “memorial park and reinterment area.” The proposals were due in July 2022 and the name of the selected consultant is forthcoming.

It appears that there is limited communication between myriad public and private groups, and with the New York State Historic Preservation Office. The convergence of the park’s diminished condition and the proposed commemorative landscape offers an extraordinary opportunity for stakeholders to come together to consider how to best honor those originally interred at the historic African American cemetery, while also advancing the park’s long overdue revitalization. Such considerations should be informed by a careful analysis of the park’s significant visual and spatial constructs to ensure that the most appropriate location to situate the reinterment and memorial site is selected, and will not adversely impact the integrity of the park.

(above) Proposed Internment Area South of Former Observatory Site. Image courtesy of City of Newburgh RFP #18.22, July 15, 2022.

What You Can Do to Help

Downing Park is likely eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (as more than 200 other Olmsted-designed landscapes have been) and may even be a potential National Historic Landmark candidate (the highest honor that can be bestowed on a historic property in the U.S.). Recognizing this exceptional significance, any new commemorative landscape feature or memorial should respect the park’s visual and spatial organization as recommended in “The Secretary of the Interior’s Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes,” which prescribes: “Identifying, retaining, and preserving the existing spatial organization and land patterns of the landscape as they have evolved over time.” The city’s recent RFP recommended the reinterment site in the upper, northeastern section of the park at the terminus of the park drive. Much like the recently stockpiled building materials, the proposed reinterment site appears to have been arbitrarily plopped in the historic designed landscape in what is being interpreted as “open space.” Alternatively, the park's pergola, constructed after the elder Olmsted and Vaux’s involvement and built on the foundation of a former farmhouse, could be rehabilitated and adapted as a focal point for commemoration and healing.

This year marks not only the bicentennial of Fredrick Law Olmsted, Sr.’s, birth, but the 125th anniversary of the opening of Downing Park. What better way to mark these significant milestones than by advancing an agenda that can heal both the community and the nationally significant park?

Newburgh Mayor, Torrance Harvey, and the Newburgh City Council, asking:

1. For improved funding of Downing Park;

2. For the city to conduct an analysis of Downing Park, exploring more appropriate locations for a reinterment area/memorial that will not adversely impact the historic design intent of the park;

3. To establish guidelines stipulating the appearance of the planned memorial and whether future memorials/burial areas will be permitted in the park.

Contact the Deputy Commissioner of NY Division for Historic Preservation, Daniel Mackay, asking to pursue National Register designation for Downing Park.

The Downing Park Planning Committee habitually welcomes donations to assist in the care and upkeep of the space. Please consider making a monetary contribution to help rejuvenate this long-neglected park.

The Downing Park Planning Committee seeks dedicated volunteers to help with park projects, from planting to pruning. Recently, the park was assisted by the Garden Club of Orange and Dutchess Counties, as well as school groups who helped to plant over 1,000 daffodils. The committee welcomes assistance from diverse community groups, including schools, churches, and scout organizations.

-

Photo by Barrett Doherty.