Entrepreneur and avid gardener William Robertson Coe hired Olmsted Brothers to revive the grounds of his estate on Long Island, Planting Fields, in 1918, beginning a fruitful collaboration that spanned decades and produced 395 plans. Now an arboretum and historic site open to the public, Planting Fields is confronting the significant challenges of maintaining the estate’s historic canopy as newly discovered diseases severely threaten its trees.

History

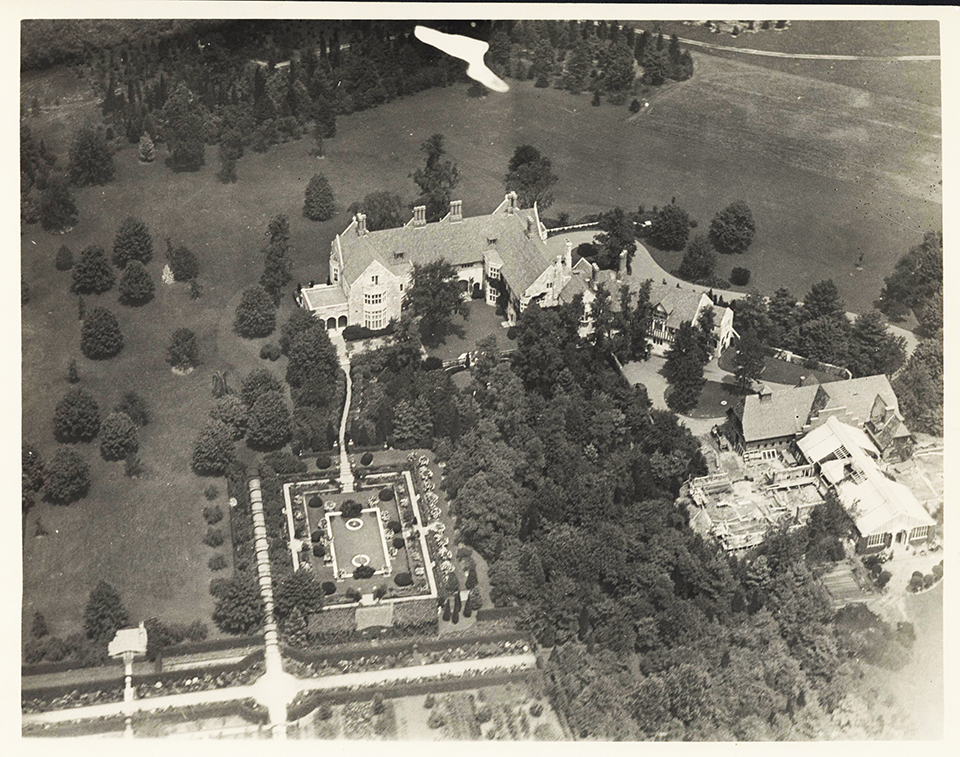

Coe Estate, Oyster Bay, New York, 1924. Photo courtesy of Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Coe Estate, Oyster Bay, New York, 1924. Photo courtesy of Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Originally cultivated by indigenous Matinecock tribes and then as a vernacular farmstead beginning in the seventeenth century, this landscape was transformed in the early twentieth century when Helen Byrne, wife of attorney James Byrne, purchased 350 acres to create a country retreat in 1904. Their residence designed by Grosvenor Atterbury (1908) and gardens designed by James Greenleaf were subsequently purchased, along with additional acreage, by English entrepreneur William Robertson Coe and his wife Mai in 1913. An ardent gardener himself, Coe commissioned Guy Lowell and Andrew Robeson Sargent to further embellish the estate with garden rooms and greenhouses for his extensive plant collection. Coe directed the transplanting of stately lindens and beeches to achieve the necessary design intent, augmenting the site’s existing trees and enriching borders and woodlands with additional plant materials, especially rhododendrons and azaleas, of which he was particularly fond, imported from his native England.

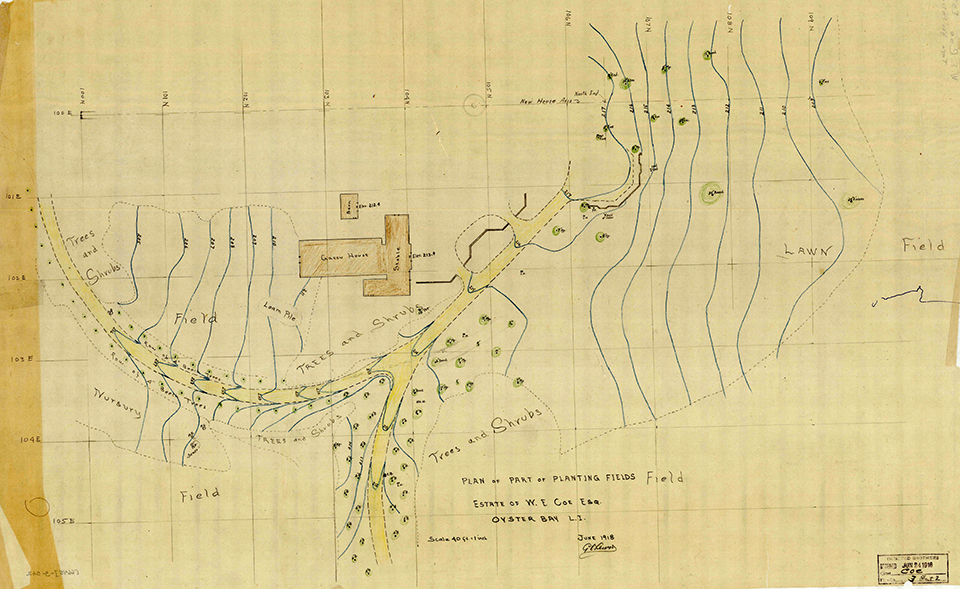

Plan of Part of Planting Fields, 1918. Photo courtesy of Planting Fields Foundation.

Plan of Part of Planting Fields, 1918. Photo courtesy of Planting Fields Foundation.

Following a devastating fire and the unexpected death of Sargent, in 1918 Coe hired architects Walker & Gillette and Olmsted Brothers with James Dawson as the design lead to construct a new, larger English Tudor Revival estate. For the next twenty years, Dawson and Olmsted Brothers (including Warren Manning, Percival Gallagher, and Percy Jones) worked closely with the Coe family to create formal and decorative gardens (such as the Italian Garden and Heather Garden) complemented by vast naturalistic woodlands and clearings. Across the lawn’s west slope, sweeping vistas are revealed by the strategic placement of oak trees. The Camellia House, first constructed under Lowell and Sargent, was enlarged by Olmsted Brothers and elevated from a utilitarian ancillary structure to a garden destination. Under the direction of Dawson, innovations in the use of heating pipes and ventilation allowed Coe’s collection of rare camellias, imported from the island of Guernsey in 1917, to be planted year-round. Olmsted Brothers also oversaw the reorganization of the site’s circulation system after the monumental, eighteenth-century iron Carshalton Gates, originally installed at London’s Carshalton Park and imported by Coe after World War I, were chosen for the site’s west entrance.

A 1921 Coe family visit to England, during which Coe noted the “very effective groups of English beeches,” likely inspired the planting of a beech copse on the property’s East Lawn. Though this stand was planted during the Olmsted firm’s involvement, its omission from their plans suggest that the feature was likely conceptualized by Coe himself.

Beech Copse, Planting Fields. Photo courtesy of Planting Fields Foundation.

Beech Copse, Planting Fields. Photo courtesy of Planting Fields Foundation.

After Coe deeded the 409-acre property to the State of New York in the 1940s, the estate was occupied by the State University of New York (SUNY) for nearly two decades before being reopened as a state arboretum in 1970. With 395 plans created and a record of correspondence spanning six decades, Olmsted Brothers’ work at Planting Fields represents one of the longest and most prolific extant commissions among the firm’s estate work, second only to Biltmore. Planting Fields was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

Planting Fields, 2022. Photo by David Almeida.

Planting Fields, 2022. Photo by David Almeida.

A 2019 Cultural Landscape Report for the estate, prepared by Heritage Landscapes, uncovered the full extent of the Olmsted firm’s involvement and spurred renewed investment in restoring and rehabilitating the firm’s significant design. In addition to recapturing the vista framed by the Carshalton Gates, rehabilitating the Heather Garden, and restoring the double allée of oak trees along the entrance drive, Planting Fields has started to confront the significant challenges of the decline of the estate’s beech copse, which has been severely affected by disease in recent years. The property contains both American and European beech, with the collection of the latter being among the largest on the East Coast.

Photo courtesy of Bartlett Tree Experts.

Threat

Two life-threatening diseases, Phytophthora bleeding canker and Beech Leaf Disease (BLD), pose an imminent threat to both species of beech at Planting Fields. The former can be treated effectively when detected early, but the volume of blighted beech trees on the property, combined with accessibility challenges posed by the site’s dense woodlands, make large scale treatments prohibitively expensive and impracticable. While most of the beech collection is at risk from the disease, only a very small portion is currently being actively treated by Planting Fields horticulture staff.

Beech Leaf Disease (BLD) was first identified in Ohio in 2012 and found at Planting Fields in 2021. It is a relatively newly discovered disease with several unknown factors that make it especially difficult to treat. Believed to be caused by microscopic nematodes (parasitic worms), BLD affects beech trees of any age. Infestations are identified by changes to the foliage, including striping, curling, texture changes, and leaf loss. At Planting Fields, this disease is progressing at a startling rate. Daily monitoring and image capturing reveals that more than half of the total number of beech trees, both natural and cultivated, have been affected. In the spring of 2022, a majority of beech trees failed to leaf out, and those that did had lost up to 80% of their leaf canopy. These majestic mature trees are among the site’s most significant living cultural landscape features and visitor attractions. In addition to their heritage value, beech trees provide habitat to numerous insects including pollinators, and the nuts produced by the trees are a key source of nutrients for wildlife.

In addressing this challenge, the Cornell University Research Center, located on Long Island, has collected samples of affected trees for pathological study. The Bartlett Tree Experts is also involved in experimental treatments of the disease. Their collective findings are regularly shared with Planting Fields staff, as well as with other arboreta and research facilities around the country.

This disease is not unique to Planting Fields. Beech Leaf Disease has so far been found to affect trees in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Rhode Island, Virginia, and Ontario, Canada, and is spreading rapidly throughout the continent. A signature element of the Picturesque landscape, beech trees were cultivated by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., at his farm in Staten Island, New York, and planted by his successor firms in estates, cemeteries, and parks across North America, including the U.S. Capitol Grounds, California’s Mountain Lake Cemetery, and the park systems of Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Baltimore, Maryland; Louisville, Kentucky; and Boston, Massachusetts. The rapid spread of this disease endangers a remarkable number of trees and forests across the continent.

What You Can Do to Help

For more information about Planting Fields, visit https://plantingfields.org/

Understand the extent and severity of Beech Leaf Disease to help prevent and limit its spread. In addition to reading about the disease, you can contact your regional forest service office, local arborists association, or agriculture extension office to acquire more localized information. As this disease was only identified a decade ago, and it continues to spread, online resources are constantly being updated.

Hear more about this disease from a pathologist and learn more about its spread from the National Park Service and Science journal.

Contribute to Scientific Research

Scientists are actively looking for research sites where they can perform work on this disease. If you own or manage a property with a beech forest, consider writing to the contact below to find out more about how to participate in vitally important research.

Andrew Loyd

Plant Pathologist, Bartlett Tree Experts

E: aloyd@Bartlett.com

Finding new infestations can help scientists investigate how Beech Leaf Disease is spreading. If you live in an affected region, look for and take photos of symptomatic trees. Close-up photos of leaves or photos of leaves held up against light (for example, taken through the canopy) are especially good for identification. Cleveland Metroparks, with support from the USDA, developed the Tree Health Survey app to allow for open-source tracking of BLD infestations across the region. Utilize the app if you’re in the area. Outside the Cleveland metro region, encourage your local park authority to implement a similar open-source tool.

In most affected states, you can also report your findings through the state forestry office.

If your property has been affected by an infestation of BLD, contact your legislative representatives to urge them to allocate more federal funds for research.

-

Photo courtesy of Bartlett Tree Experts.