The 1956 Battle of Central Park pitted New York City Park Commissioner Robert Moses against more than 50 mothers and their children on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. At issue was a half-acre wooded site on the edge of Central Park, next to the West 67th Street Playground, which Moses wanted to redevelop to include an 80-car parking lot for the restaurant Tavern on the Green. Skirting sit-downs and other protests, Moses surreptitiously began having trees felled; the ensuing furor led to State Supreme Court Justice Samuel Hofstadter issuing a temporary injunction. Following further legal action, including two lawsuits, Moses abandoned the plan. Instead, the West 67th Street Playground designed by Richard Dattner became the first free-standing Adventure Playground in 1967 and was followed by the adjacent space, now called the Tarr-Coyne Tots Playground, built on the site of the 1956 protest, in 1968.

History

Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., and Calvert Vaux’s “Greensward” plan was chosen for New York’s precedent-setting, publicly funded, urban park in 1857. Their proposal, with pastoral meadows and Picturesque woodlands, was designed as a place of respite for city residents. They were criticized in the press, while the park was under construction in 1858, for not including a play area for children, so Olmsted and Vaux added a “Children’s District” mid-park at 65th Street. It embodied nineteenth century ideas about children’s recreation and included: “the Dairy,” where children could buy milk and other refreshments; “the Kinderberg Shelter,” a large wooden structure that provided shade and seating; and a playground with a meadow with wooden swings, seesaws, and a small building with athletic equipment.

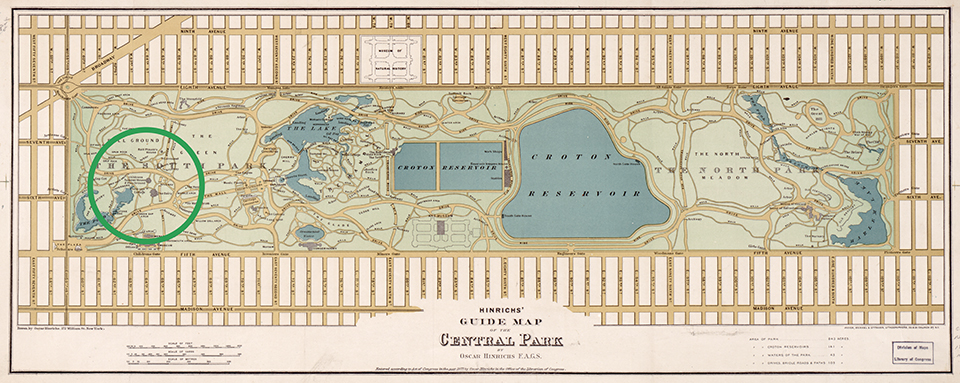

Map of Central Park with “Children’s District” Circled, 1875. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Map of Central Park with “Children’s District” Circled, 1875. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

By 1926, wear and tear on the playground created pressure for repairs. That year philanthropist August Heckscher funded the installation of a wading pool, play equipment, and open space. Now known as the Heckscher Playground, it is located mid-park between 61st and 63rd streets, on the periphery of the original “Children’s District.” Its placement, landscape architect Hermann Merkel noted in 1926, preserved park views and thus the overall feeling of Olmsted and Vaux’s original design.

View of “Boy’s Playground, Central Park,” circa 1900. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

View of “Boy’s Playground, Central Park,” circa 1900. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

During the pervasive financial hardship of the Great Depression, the election of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia in 1934 ushered in a new era of public investment that reshaped New York. One of the mayor’s first initiatives included equipping play areas in Central Park, which his appointed Park Commissioner, Robert Moses, and landscape architect Gilmore Clarke began planning with funds from the Works Progress Administration.

Seven years later, Moses had incorporated twenty new playgrounds, eighteen of which were located along the park’s perimeter to facilitate easy access for nearby residents, including one at West 67th Street. Though created as play spaces, an emphasis was placed on using durable materials to withstand heavy use, which resulted in playgrounds that were asphalt-paved and sparsely furnished. Each one was staffed with several full-time attendants who oversaw play activities. Despite evolving ideas about the importance of play to children’s psychological development, the playgrounds were never updated during Moses’ tenure at the Parks Department. Ultimately it would be a playground dispute that marked the beginning of the end for Moses’ career.

Mothers vs. Moses

In 1956, Moses planned to build a parking lot in a wooded area for the Tavern on the Green restaurant adjacent to the West 67th Street Playground. Many local mothers let their children play in the wooded lot because the neighboring playground had a set of stairs that prevented stroller access and limited equipment for older children.

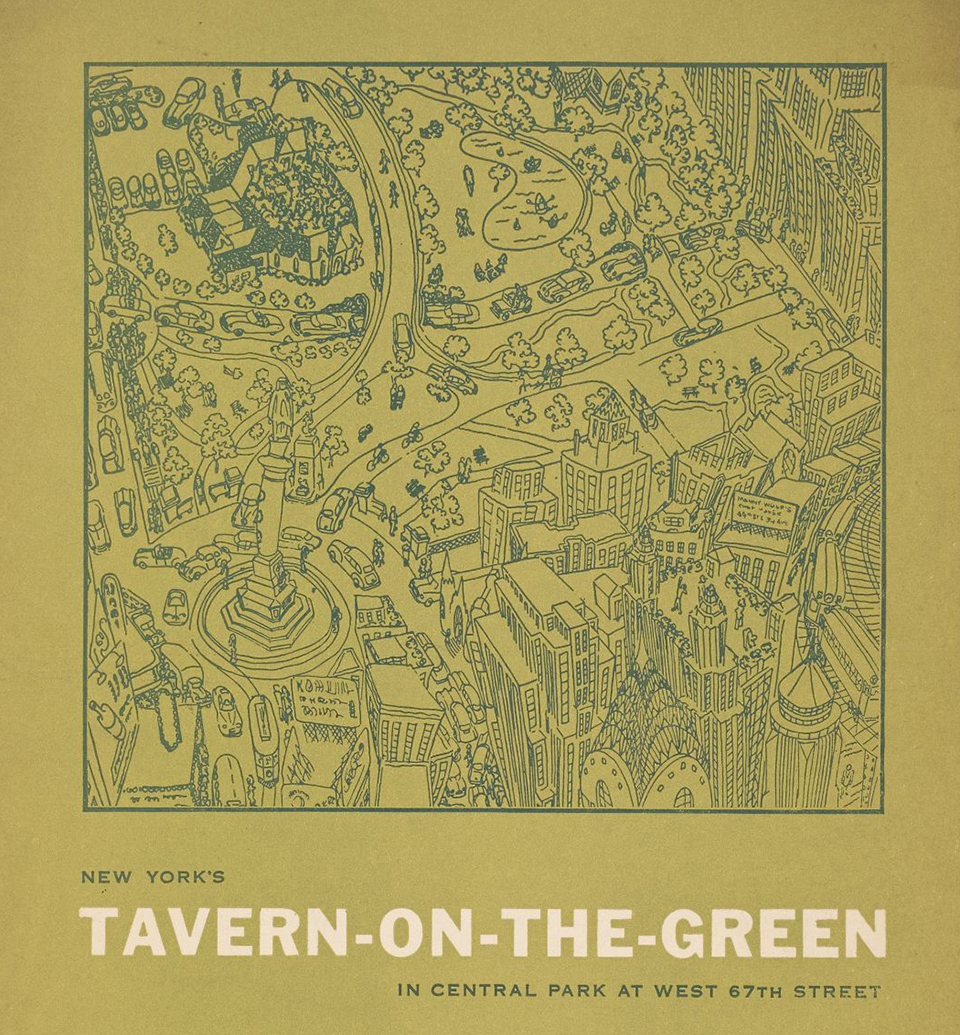

‘Tavern on the Green’ menu showing the restaurant (top left) within Central Park, 1956. Courtesy Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library.

‘Tavern on the Green’ menu showing the restaurant (top left) within Central Park, 1956. Courtesy Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library.

When the mothers learned that the lot would be cleared, they occupied the site along with their children and dogs; they set up chairs and refused to leave. Local newspapers dubbed the protest “The Battle of Central Park.” After a week of being thwarted by women the New York Times referred to as “six housewives,” one night Moses ordered that the site be fenced off and called in police to issue restraining orders as distraught protestors arrived. As a construction crew cut down trees, photographers documented the reactions of the mothers, which were published in newspapers the following day. In response to Moses’ intransigence, the women filed a taxpayer’s suit, arguing that the proposed parking lot (for a restaurant most park visitors couldn’t afford) was a questionable use of public parkland. As public opinion turned on Moses in favor of the mothers who had advocated for a space for their children, the city’s corporation counsel reached an arrangement with the lawyer engaged by the mothers to delay the case until the public outcry had dissipated so that Moses could announce he would build a playground in place of the parking lot.

Mothers and children protest during “The Battle of Central Park,” 1956. Photo by Tom Baffer, Courtesy New York Daily News Archive - New York Daily News via Getty Images.

Mothers and children protest during “The Battle of Central Park,” 1956. Photo by Tom Baffer, Courtesy New York Daily News Archive - New York Daily News via Getty Images.

Instead of restoring the wooded area, the Parks Department installed new play equipment atop the partially built parking lot, adjacent to the existing, little-used West 67th Street Playground. The Battle for Central Park represented a turning point in children’s recreation as the mothers successfully made their case for prioritizing children’s play areas over parking infrastructure, and their efforts laid the groundwork for further advocacy on behalf of the city’s children and the appropriate use of public parkland.

The same protest tactics were deployed again in October of the same year, when the Parks Department announced it could no longer fund full-time staff for Central Park playgrounds. A group of mothers who frequented a playground near West 110th Street gathered with signs highlighting their concerns but were prevented from picketing by police. While Moses’ tenure as commissioner expanded the city’s playgrounds from 119 to 777, his legacy was called into question by a growing number of people, including many who turned against him for defacing a beloved wooded glen, which one mother described as, “the center of our neighborhood.”

Photo by Charles A. Birnbaum, 2024.

Visibility

The Battle of Central Park initiated activism by mothers and park advocates for children’s play that forever reshaped community engagement in the design and stewardship of the city’s playgrounds. In 1963, a new generation of residents formed the Mother’s Committee to Improve the West 67th Street Playground in response to increasing injuries at Moses’ inhospitable, ill-maintained playgrounds off West 67th Street. After the Parks Department attempted to address safety concerns by adding rubber mats under play equipment, the mothers reorganized and changed their name to the Committee for a Creative Playground. As a result of their advocacy, Commissioner Thomas Hoving and the Estée and Joseph Lauder Foundation engaged architect Richard Dattner to redesign the Moses-era playgrounds. The West 67th Street Playground became the first Adventure Playground in 1967 and was followed by the adjacent Tots Playground, built on the site of the 1956 protest, in 1968.

In recent years, both playgrounds have undergone rehabilitation efforts to meet present-day safety standards and, importantly, to retain the Adventure Playground aesthetics. The Tots Playground was rebuilt in 1987, and rehabilitated in 2013 (when it was renamed, Tarr-Coyne Tots Playground). The West 67th Street Playground, whose historic design significance was acknowledged by the Central Park Conservancy (CPC) in response to the advocacy efforts of Landmark West! and others, was rehabilitated in 1997 and again in 2015.Today, the best reminder of the efforts by local mothers in 1956 to improve the city’s playgrounds is the design of the playgrounds themselves. While neither appears as they did at the time of the protest, both reflect the results of ongoing advocacy inspired by the initial protest. Additionally, the parkland areas surrounding the playgrounds still host several living witness trees to those events. The CPC does attribute the existence of the Tarr-Coyne Tots Playground to the 1956 Battle of Central Park on their website.

Central Park was designated a National Historic Landmark (NHL) in 1966, one year prior to the creation of the West 67th Street Playground and two years before the establishment of the Tots Playground. While the nomination indicates the park’s period of significance from 1857-1866, it notes that “the gradual growth and development of the park are considered part of the landmark. These include the Arsenal, the Zoo, Bethesda Fountain…and all of the arches and bridges created as part of the circulation system through the park.” The nomination explicitly calls out “modern tennis courts, skating rinks [and] cemented playgrounds,” writing that they “disrupt the landscape design…[and] do not contribute to the national significance of the landmark.”

In 2017, Central Park was added to the United States’s Tentative List for nomination to the World Heritage List of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). In preparing the nomination on behalf of the U.S. Department of the Interior, the Central Park Conservancy is revisiting earlier designation reports (i.e. National Historic Landmark and a Scenic Landmark of the City of New York) to present a more thorough and nuanced description of its cultural and design history (Battle of Central Park, adventure-style playgrounds etc.). The effort has informed the Conservancy’s ongoing work to incorporate more of the park’s rich cultural and social history into the online content and public programs offered by the organization.

What You Can Do to Help

As those protesters and advocates for children’s play space pass away and/or their plight is forgotten, the saga of how they made their voices heard and improved public playgrounds for generations is in danger of being lost and forgotten. While the presence of the West 67th Street and Tarr-Coyne Tots Adventure Playgrounds is a tribute to the efficacy of their engagement, there is an opportunity to make visible and commemorate their inspiring collective efforts.

April 2026 will mark the 70th anniversary of mothers squaring off with construction crews during “the Battle of Central Park.” Commemorative events could serve as a catalyst for a targeted effort to capture the oral histories of those who organized, participated in, chronicled or witnessed the protests.

Recently Landmark West! (which has secured landmark status for numerous buildings and historic districts in Manhattan’s Upper West Side since 1985) produced oral histories about the San Juan Hill community. The opportunity exists to produce additional oral histories focused on the Battle of Central Park.

Contact Landmark West! to recommend that the organization produce oral histories with those associated with the Battle of Central Park and donate to organization to support the potential oral history project.

Landmark West!

45 West 67th Street, Front 1, New York, NY 10023

T: (212) 496-8110

E: landmarkwest@landmarkwest.org

Following recent precedents in which New York City playgrounds and state parks have been renamed to commemorate activists, including Marsha P. Jonhson and Al Quiñones, Tarr-Coyne Tots Playground could be renamed to honor the mothers who protested on behalf of their children and Central Park. Additionally, interpretive materials could be introduced at the playground, including wayside signage depicting the standoff between the mothers with their children and pets, and the construction crews and large machinery surrounded by police.

Contact the Central Park Conservancy to recommend increasing the visibility of the Battle of Central Park through onsite interpretation and renaming Tarr-Coyne Tots Playground to honor the mothers.

Central Park Conservancy

717 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY, 10022

T: (212) 310-6672

E: https://www.centralparknyc.org/contact-us

-

Photo by Barrett Doherty, 2024.