This small 22.5-acre island in San Francisco Bay, site of the first lighthouse on the West Coast (1854), was once a fort, a military prison, and a federal penitentiary. In 1963, the prison closed and the island was left vacant. On March 9, 1964, five Lakota Sioux landed on the island and briefly claimed it as “Indian Land.” A more protracted occupation of Alcatraz by the “Indians of All Tribes” lasted nineteen months, from November 20, 1969, to June 11, 1971, and at its peak, involved more than 400 Native Americans. The protest was significant as it galvanized the Native American “Red Power” tribal and treaty rights movement, drawing national and international attention to Native American struggle for sovereignty and self-determination.

History

The word "Alcatraz" is an English corruption of "Alcatraces," the Spanish word for the seabirds known as "gannets" (though some sources say “pelicans” or “cormorants”). The Spanish naval lieutenant Don Juan Manuel de Ayala gave this name in 1775 to the island in San Francisco Bay. By the time the first Europeans arrived in 1769, the Bay Area was home to a thriving network of Ohlone and Coastal Miwok communities who had developed land management techniques to assist with their hunting, fishing, and harvesting. While there is no evidence that Alcatraz ever hosted a long-term settlement, surviving oral histories indicate the island was used for camping, foraging, and to temporarily isolate community members who broke tribal laws and taboos.

The establishment of Franciscan missions soon after the arrival of the Spanish transformed the nearby communities. During this time, Alcatraz itself was used as a hiding place for people looking to escape the mission system. Estimates suggest that a population of over 20,000 at the time of the first encounter had fallen to less than 2000 by 1810. Descendants of the original communities continued to live at the missions until the system was abolished in 1834.

Following its American acquisition in 1848, Alcatraz was turned into a fortress beginning in 1853 and a military prison was established in 1861. Throughout the nineteenth century its buildings were constructed of masonry and brick (the fortifications, citadel, etc.) or wood frame (living quarters, warehouses, and other support structures).

View of Eastern Side of Alcatraz Island, 1934-1963. Courtesy McPherson/ Weed Family Alcatraz Collection, National Park Service.

View of Eastern Side of Alcatraz Island, 1934-1963. Courtesy McPherson/ Weed Family Alcatraz Collection, National Park Service.

As the island's value as a prison eclipsed its import as a fortification, a complex of a newer prison and support buildings was erected beginning in 1909 and continuing after 1934 by the Federal Bureau of Prisons. During this time the old fortifications and their support buildings were either wholly or partially obliterated, or altered, and replaced with buildings of steel-reinforced concrete. Alcatraz closed as a prison in 1963 at which time the island was largely abandoned. Since 1972, Alcatraz Island has been part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, a unit of the National Park Service.

The Occupation

There were three occupations of Alcatraz Island by Native Americans in the 1960s: the first two, on March 9, 1964, and November 9, 1969, were extremely brief. The third, beginning November 20, 1969, lasted nineteen months. The March 1964 event occurred when five Sicangu Lakota Indians, led by Belva Cottier and her cousin Richard McKenzie, landed on Alcatraz and declared it as Indian Land. They cited the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty that said deserted federal land could be returned to the Sioux.

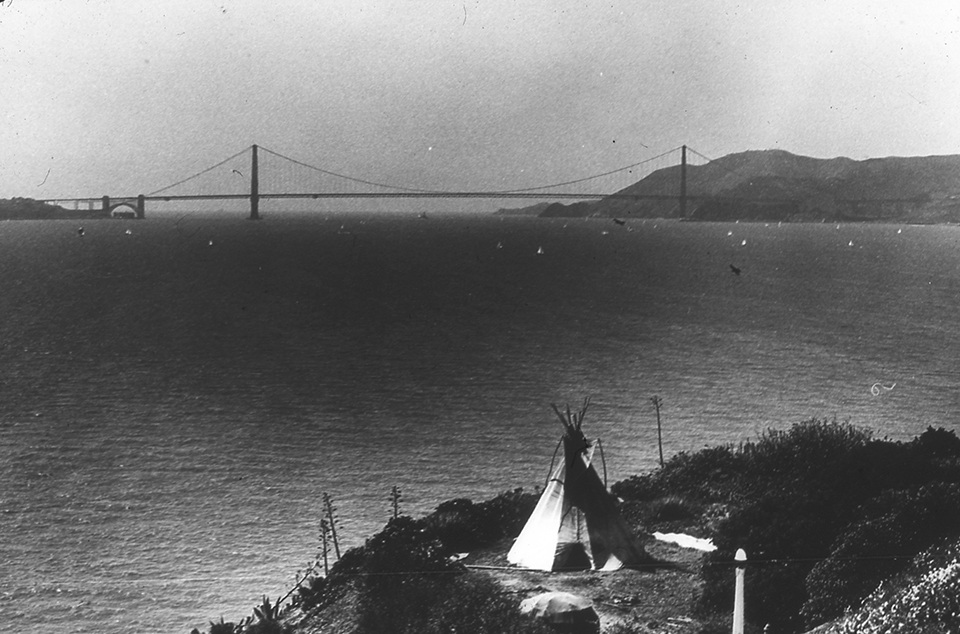

Tipi on Alcatraz Island During Occupation, Courtesy Don DeNevi Alcatraz Photograph Collection, National Park Service.

Tipi on Alcatraz Island During Occupation, Courtesy Don DeNevi Alcatraz Photograph Collection, National Park Service.

The protests focused on centuries of colonial and U.S. policies that had forcibly displaced tens of thousands from their land, wrested control over their livelihood, culture, government, and resources, and resulted economic marginalization and political repression. This also came against the backdrop of nationwide activism concerning the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, gender equality, the environment, and numerous other issues.

Some of the federal level policies that contributed to the protests included those of termination (1953) and relocation (1956); collectively these policies aimed to eliminate more than 100 tribes as sovereign nations and sell their land, and assimilate more than 200,000 Native Americans by moving them to numerous cities including San Francisco. In fact, by 1970 some 40,000 Native Americans lived in the Bay Area, some had been there for decades, while others arrived as part of termination and relocation policies. An important gathering place in San Francisco was the Indian Center located on 16th Street in the heart of the Mission District, which offered housing and job placement assistance and tutoring by students from San Francisco State University.

Along with the federal level policies, beginning in 1968 local university students who were part of the Third World Liberation Front were agitating for curricula at S.F. State and the University of California at Berkeley that represented African American history, Chicano history, Native American history, and that of other minority groups and people of color. Strikes by students over several months were met with violence, which attracted national media attention. Eventually, S.F. State and U.C. Berkeley established ethnic studies programs.

One month before the nineteen-month-long occupation began on November 20, the Indian Center burned down; this proved to be a final catalyst for the occupation. Following a brief one-day landing on November 9, eleven days later nearly 100 people arrived, including dozens of Native American students from the University of California at Los Angeles. They chose the name “Indians of All Tribes” to represent the group. They wanted the deed to the island and to establish an Indian university, a cultural center, and a museum.

Thanksgiving Celebration in Alcatraz Island Recreation Yard, 1969. Courtesy National Park Service.

Thanksgiving Celebration in Alcatraz Island Recreation Yard, 1969. Courtesy National Park Service.

The occupation was led by: Richard Oakes, the first coordinator of Native American Studies at S.F. State and a Mohawk originally from the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation in Upstate New York known as Akwesasne, on the U.S./Canadian border; and LaNada Means (now Dr. LaNada War Jack), who came to San Francisco as part of the federal relocation policy and was the first Native American admitted to U.C. Berkeley in 1968. She was a member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in Idaho. Telegenic and outgoing, Oakes became the spokesperson and when asked by a reporter “why Alcatraz?” he replied: “On one end of the country you have the Statue of Liberty. This is just the opposite. You have a true reality of liberty.”

Children on Alcatraz Island, 1970. Photo by Bengt af Geijerstam/Studio 8-10. Courtesy National Park Service.

Children on Alcatraz Island, 1970. Photo by Bengt af Geijerstam/Studio 8-10. Courtesy National Park Service.

At its peak, some 400 people occupied the island. They established supply routes that evaded the Coast Guard and even set up Radio Free Alcatraz, broadcasting from Berkeley, Los Angeles, and New York. Oakes and his family left the island after the accidental death in January 1970 of one of his five stepchildren, twelve-year-old Yvonne. Non-Native Americans including those from the San Francisco hippies and drug culture and others joined the protest; drugs and alcohol, which had been initially banned, became common place. Because of public support, the federal government chose to wait the occupation out rather than attempt an invasion and removal by force. Moreover, President Richard Nixon, who had pledged to end termination, didn’t want bloodshed (the Kent State Massacre on May 4, 1970, both horrified the nation and created further county-wide unrest). However, following waning public support amid press reports of violence among the occupiers, federal agents and others arrived on June 10, 1971, and removed the last occupants.

Photo by Marion Brenner, 2024.

Visibility

While the Alcatraz occupation was unsuccessful in claiming deed to the island, it did spur similar protests and occupations during that nineteen-month period and many more afterwards. According to Dr. Troy Johnson, an expert on Native American activism: “Many of the approximately seventy-four occupations that followed Alcatraz were either planned by or included people who had been involved in the Alcatraz occupation or certainly gained their strength from the new 'Indianness' that grew out of that movement.” In addition, the U.S. Congressional passed legislation to “support tribal self-rule, foster cultural survival as a distinct people, and to encourage and support economic development on Indian reservations.” According to the National Park Service: “The underlying goals of the Indians on Alcatraz were to awaken the American public to the reality of the plight of the first Americans and to assert the need for Indian self-determination. As a result of the occupation, either directly or indirectly, the official government policy of termination of Indian tribes was ended and a policy of Indian self-determination became the official U.S. government policy.” The National Park Service has done much to integrate the occupation of Alcatraz into the park’s core mission and vision. The park’s website opens, “Alcatraz reveals stories of American incarceration, justice, and our common humanity. This small island was once a fort, a military prison, and a maximum-security federal penitentiary. In 1969, the Indians of All Tribes occupied Alcatraz for 19 months in the name of freedom and Native American civil rights. We invite you to explore Alcatraz's complex history and natural beauty.” This expansion and broader inclusion of the significant events sets that took place at Alcatraz sets the stage for park management, stewardship and interpretation – a holistic approach that embraces the full palimpsest of activities that took place at the historic site.

In 2017 the International Coalition of Sites of Consciousness, a global network of historic sites, museums and memory initiatives that connects past struggles to today's movements for human rights, designated the Golden Gate National Recreation Area an International Site of Conscience. The aim is to recognize “centuries of overlapping history from California’s indigenous cultures, Spanish colonialism, the Mexican Republic, U.S. military expansion and the growth of San Francisco.

Today on Alcatraz visitors can see the political messages painted onto various walls, including at the island’s ferry landing site, and the side of the water tower. A 50th anniversary commemoration was held in 2019, which coincided with the opening of the exhibition “Red Power on Alcatraz: Perspectives 50 Years Later” that ran for nineteen months. Annually in late November events are held to remember the occupation.

For those unable to visit the island, the National Park Service website includes an essay by Dr. Johnson about the occupation among the "Stories" embedded within in the Alcatraz Island Cultural Landscape. Moreover, both the listing in the National Register of Historic Places and the designation as a National Historic Landmark include the occupation within the site’s period of significance.

Additionally, the website for Dr. LaNada War Jack, one of the first occupiers to arrive on Alcatraz in 1969 and one of the last to leave in 1971, contains compelling resources, including video interviews with Dr. War Jack and footage of the occupation.

What You Can Do to Help

The National Park Service recommends supporting the work of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, their non-profit partner, through donations and/or volunteer work to help maintain the site's historical integrity. They also want to hear from those individuals who have personal family ties to the occupation, as they are working on preserving any archival records and/or potentially recording oral histories of the events surrounding the occupation.

Alcatraz Island

Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy

201 Fort Mason, San Francisco, CA 94123

T: (415) 561-3044

https://www.nps.gov/alca/getinvolved/supportyourpark/partners.htm

In addition, the public can raise awareness of the Red Power movement and the ongoing struggles for tribal sovereignty and self-determination through social media, attending commemorative events, and engaging with educational resources about the Red Power movement.

-

Photo by Marion Brenner, 2024.