Incorporated in 1896 Miami’s population of several hundred grew steadily over the subsequent decades to nearly 30,000 people in 1920, approximately 31 percent of whom were African American; by 1930 the population had soared to more than 110,000. During this time of growth, the city’s beaches were developed in earnest, but because of the “separate but equal” doctrine established by the landmark 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson, African Americans were denied entry to all the city’s oceanfront beaches.

History

In the 1920s African Americans began to visit Virginia Key, an isolated, undeveloped and relatively uninhabited barrier island located approximately one mile southwest of the tip of Miami Beach. The island, accessible only by boat, attracted church groups, who gathered for sunrise services and ocean baptisms, as well as bathers who would swim at Bears Cut (also known as Beers Cut), a narrow body of water at the southern edge of the key.

Swimmers at Virginia Key Beach. Photo by Richard B. Hoit. Courtesy of Virginia Key Beach Park Trust.

Swimmers at Virginia Key Beach. Photo by Richard B. Hoit. Courtesy of Virginia Key Beach Park Trust.

In 1938 the city adopted a plan to establish a seaport on Virginia Key and in 1940 County Commissioner Charles Crandon secured 808 acres of Key Biscayne, located immediately south of Virginia Key, for a “whites-only” public park, named in his honor. Crandon advocated for a causeway to connect the mainland and two islands, which was begun in 1941 and completed in 1947.

During World War II the Navy trained African American seamen at Virginia Key Beach and in 1945 Crandon announced plans to establish a “half mile negro bathing beach” on the island adjacent to a proposed airport-seaport project. Authorities argued over the location of the new airport and plans to develop a segregated African American beach languished for months. Ultimately, it was a collective act of civil disobedience, organized by attorney Lawson E. Thomas and others, that turned the promise of an officially recognized and designated African American beach into a reality.

On May 9, 1945, one day after VE Day (Victory in Europe Day), six African American men and women, clad in bathing suits, defiantly waded into the Atlantic Ocean at the “whites-only” Baker’s Haulover Beach (now Haulover Park) northeast of downtown Miami. The goal was to challenge racial segregation at public beaches. Thomas waited on the shore (with $500 for possible bail money), anticipating that the police would arrest and jail the protestors, thus creating public controversy. When the police arrived the protestors (including Otis Mundy, May Dell Braynon, Annie Coleman) were ordered out of the water but were not arrested. Sheriff D.C. Coleman contacted Commissioner Crandon who asked Thomas to meet the next morning to “work something out.” As professor, historian, and activist Gregory W. Bush notes, “In a city that depended on upon tourism for its economic livelihood, the white power structure needed to avoid ugly racial confrontations.”

As a direct result of the “wade-in” Virginia Key Beach was dedicated approximately three months later, on August 1, as a “colored only” park. The creation of Virgina Key Beach was a symbolic victory for Miami’s African American community and, immediately became a popular destination. Nonetheless, Miami’s beaches remained segregated for another fourteen years.

Visitors at Virginia Key Beach, 1956. Courtesy of Virginia Key Beach Park Trust.

Visitors at Virginia Key Beach, 1956. Courtesy of Virginia Key Beach Park Trust.

During the Civil Rights Movement, the city’s African American leaders strove to integrate public facilities and again looked to the city’s public beaches. In November 1959, Rev. Theodore Gibson and other members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) called for the county to “open all tax supported county facilities to all citizens,” according to a contemporaneous Miami Times report. County Attorney Darrey Davis recommended County Manager O.W. Campbell not to comply, but suggested “an impartial board be named to gather facts as the first step toward setting up a program to integrate county parks, beaches, and hospitals.”

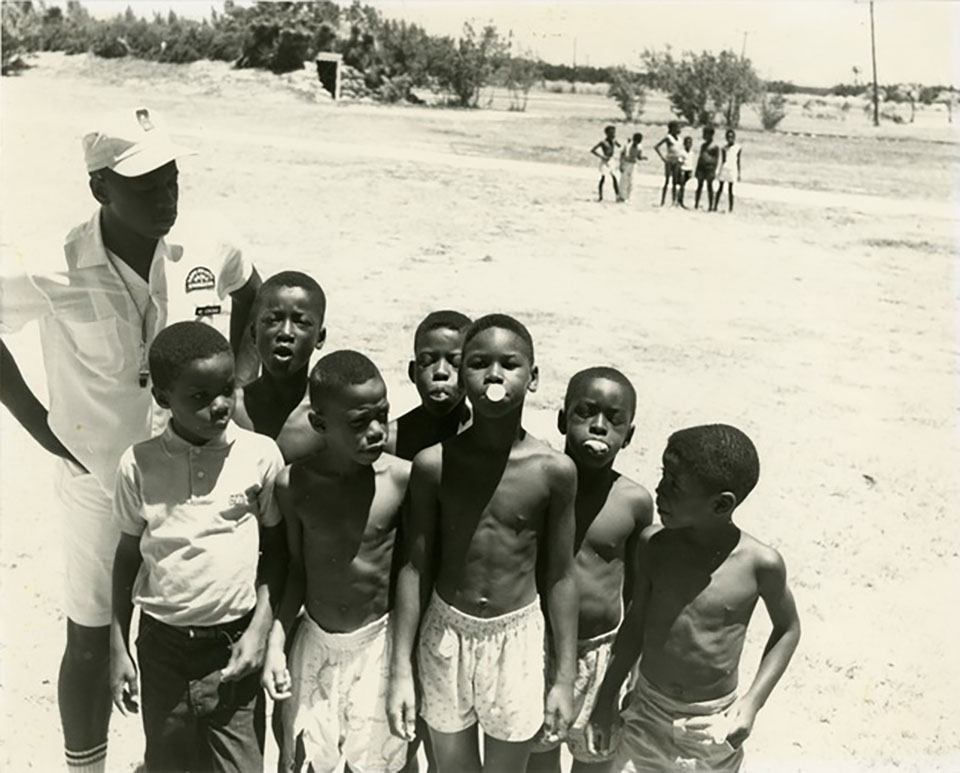

Children enjoying the beach. Courtesy of Virginia Key Beach Park Trust.

Children enjoying the beach. Courtesy of Virginia Key Beach Park Trust.

One member of Gibson’s group that met with Campbell was attorney G. E. Graves. When Campbell rebuffed the group’s request, Graves pointed out that since County Attorney Davis had already “admitted there is no law to ban Negroes from county tax supported parks,” they would begin to use previously segregated parks. In late November 1959, Rev. Gibson and a group of African American women and men went to the segregated beach at Crandon Park. As with the event at Haulover Beach fourteen years earlier, the gathering was peaceful. The Miami Times reported that “[c]urious whites gathered to watch the group as a horde of TV cameramen and reports took pictures and interviewed leaders of the group. A Metro patrol made its usual tour,” but otherwise took no action. This effectively marked the desegregation of the county’s facilities.

Photo by Rodrigo Gaya, 2024.

Visibility

In 1982 the beach was transferred from the county to the city of Miami with the stipulation that the site remain open and maintained as a public park. Soon after, however, the city closed the park, citing the high cost of maintenance and operations. In 1999 the Virginia Key Beach Park Civil Rights Task Force was established in response to plans to privately develop the site and later that year the Miami City Commission established the Virginia Key Beach Park Trust to oversee the park’s rehabilitation. In 2001 county commissioners allocated five million dollars to establish a museum on site to commemorate the park’s African American history and the following year, 77 acres of park were listed in the National Register of Historic Places for its association “with the history of the African American population of the City of Miami and surrounding areas.”

Following this recognition, a commemorative marker was installed at the park in 2006, noting the site’s significance to the local African American community. The sign credits the park’s creation to “a bold protest led by Attorney Lawson E. Thomas and others to demand an officially designated beach” (Baker’s Haulover Beach “wade-in”) and notes “another courageous protest” that “brought segregation to an end” (Crandon Park “wade-in”). In February 2008 the city reopened the park, renamed Historic Virginia Key Beach Park, and in September that year the National Park Service published a “Special Resource Study” to “assess the potential of the site for inclusion as a unit of the National Park System.” The report notes that the 1945 “wade-in” demonstration was an “early instance of a successful planned nonviolent act of civil disobedience” and served as a catalyst for the official creation of Virginia Key Beach Park. The study ultimately concludes that “although the [Virginia Key Beach] park does not meet all the criteria, it is an important historical and cultural site” that “deserves recognition for its role in the history of civil rights in Miami.”

Virginia Key Beach Park and its history is documented extensively by online and on-site interpretation. In addition to the 2006 commemorative marker the park includes a “Timeline Garden” that conveys the history of the site. Incorporating a restored coastal dune undertaken by the Army Corps of Engineers in 2013, the “garden” features interpretive signs set among naturalized vegetation. Additionally, the Virginia Key Beach Park Trust offers free weekly interpretive tours of the park in which educators discuss the “wade-in” protests. The welcome center includes a permanent exhibition that presents photographs and materials outlining the park’s history.

On-site interpretation is complemented by online resources on the Trust’s website, including videos and a virtual tour. The website details the 1945 “wade-in” on multiple pages, and it links to a digital resource, “Virginia Key Beach and South Florida’s Wade-Ins,” which discusses the 1945 and 1959 protests. Additionally, the Trust’s website links to The Virginia Key Beach Park Trust archive, held by Florida International University, which features a trove of historic and contemporary images documents and ”rough cut” oral history, video interviews.

Other organizations, including the Bridge Initiative, have raised the visibility of the “wade-in” protests and of Virginia Key Beach in several ways. The Bridge Initiative’s “Connect the Bay” program reveals the significance of Virginia Key Beach Park, Haulover Park, and Crandon Park, and the organization is currently exploring the listing of the area as a National Heritage Area.

In 2020 the Florida House of Representatives and the Florida Senate passed a resolution proclaiming August 1 of that year and each August 1 thereafter as, “Historic Virginia Key Beach Park Day,” commemorating the official creation of the park. Numerous events have been held at Historic Virgina Key Beach park commemorating its creation and history, including a symbolic “wade-in” on November 12, 2022.

Aside from a 2015 gathering and “wade-in” at Haulover Park to commemorate the 70-year anniversary of the historic event, commemorative gestures have been focused on Virginia Key Beach Park. While Haulover and Crandon Parks witnessed the courageous protests that engendered change for the city’s African American community, they are not interpreted through tours or with permanent on-site interpretive markers as at Historic Virginia Key Beach Park. While the Greater Miami Convention & Visitors Bureau includes information about the 1945 protest at Haulover Beach on the webpage for Historic Virginia Key Beach Park, corresponding information on their Haulover Beach Park webpage is absent, as is information about the 1959 “wade-in” on their Crandon Park Beach webpage. Moreover, information about the respective “wade-ins” is not included on the Miami-Dade County webpages for Haulover Park and Crandon Park.

What You Can Do to Help

Contact the Historic Virginia Key Beach Park Trust to learn how to support their work through volunteer activities, donations, and other ways; and to recommend that they apply to be listed in the National Park Service’s African American Civil Rights Network.

Historic Virginia Key Beach Park

4020 Virginia Beach Drive, Miami, FL 33149

T: (305) 960-4600

E: Info@VirginiaKeyBeachPark.net

Contact Miami-Dade County Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces about putting interpretive markers at Haulover and Crandon Parks to commemorate the “wade-ins”; and recommend adding information about the “wade-in” protests on the websites for Haulover Park and Crandon Park.

Maria I. Nardi, Director

Miami-Dade County Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces

275 NW 2nd Street, Miami, FL, 33128

T: (305)755-7800

E: maria.nardi@miamidade.gov

Contact the Bridge Initiative and learn how to support their efforts to create a feasibility study to have the U.S. Congress declare the region a National Heritage Area:

Kate Fleming

E: kate@bridgeinitiative.org

-

Photo by Rodrigo Gaya, 2024.