Founded in 1865, incorporated in 1867, and supported financially by the American Missionary Association, a New York-based Protestant-based abolitionist group, Fisk University, a prominent HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities), was designed, in part, by landscape architects Olmsted Brothers and David Williston. A significant event took place on June 21, 1924, when W.E.B. Du Bois, an alumnus and prominent civil rights activist, delivered a commencement address in which he challenged university president Fayette McKenzie’s autocratic administrative practices. That fall students protested and boycotted classes to force McKenzie out. When arbitration yielded no resolution, the students initiated a strike and departed the campus in protest. The board of trustees intervened, and McKenzie resigned in April 1925.

History

The Fisk Free Colored School was established in 1865, held its first classes on January 9, 1866, and was incorporated as Fisk University, an institution for higher learning, in 1867. The school was supported financially by the American Missionary Association, a New York-based Protestant-based abolitionist group, and named in honor of Union General Clinton B. Fisk of the Tennessee Freedmen's Bureau. Fisk provided the new institution with facilities in “government buildings, west of the Chattanooga depot, known at that time as the Railroad Hospital,” a former Union Army facility near the present site of Nashville's Union Station.

Fisk was one of several so-called freedmen’s colleges and schools established in Nashville during this period that were funded by mostly white religious organizations and philanthropists in the north. The influence of these financial supporters became a source of tension as African Americans sought to have greater control over their institutions’ administrations. Moreover, by the end of the century there was a growing divide about whether education for African Americans should be more trade-focused, as advocated by Fisk alumnus Booker T. Washington and northern funders, or liberal arts-oriented, the position of W.E.B. Du Bois, another Fisk alumnus and prominent civil rights activist.

By 1871 Fisk needed a new site because of the deteriorating condition of its existing facilities. Needing cash, the university created a chorus, the Jubilee Singers, which performed in the northern states and Europe generating enough income to fund the purchase the former site of Fort Gillem in 1873. The first two university buildings, Jubilee Hall (1874) and the music annex, were constructed, followed by the memorial chapel in 1892.

Fisk University Jubilee Singers, 1872. Photo by James Wallace Black, Courtesy Library of Congress.

Fisk University Jubilee Singers, 1872. Photo by James Wallace Black, Courtesy Library of Congress.

By 1915 the university was in dire financial straits and the board of trustees hired as president Dr. Fayette Avery McKenzie, a white professor with a PhD in American Indian studies who would focus on shoring up the university finances through an extensive fundraising campaign.

McKenzie also made administrative changes to appease donors. Along with enforcing “archaic” dress and social codes, McKenzie shut down or banned the student council, student newspaper, fraternities and sororities, baseball and track teams, campus concerts, and the formation of a campus chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Fisk students, including returning veterans of World War I, increasingly opposed his presidency.

View of Addison Avenue (now 17th Avenue South) towards Jubilee Hall, circa 1899, Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

View of Addison Avenue (now 17th Avenue South) towards Jubilee Hall, circa 1899, Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

On June 2, 1924, distinguished alumnus, W. E. B. Du Bois, delivered a commencement address to Fisk alumni, McKenzie, and other university officials. Du Bois excoriated McKenzie ‘s changes, which Du Bois understood as control of self-expression and therefore incompatible with education. Du Bois referenced events at Harvard University in which students publicly advocated for their right to invite speakers to the campus for the purpose of education. He “wonder[ed] what would happen if the students of Fisk University made a similar protest.” He continued, “Or rather I don’t wonder. The ring leaders would be expelled. And yet in years to come a list of the expelled students of Fisk University bids fair to become a roll of honor, of those who would not be crushed and who would not give up, who would be free.” Consequently, tension between the African American students and the white administrators and donors spilled into the divided community. Finally, Du Bois published an article in The Crisis, the NAACP’s magazine, that called for a boycott of the university until McKenzie resigned.

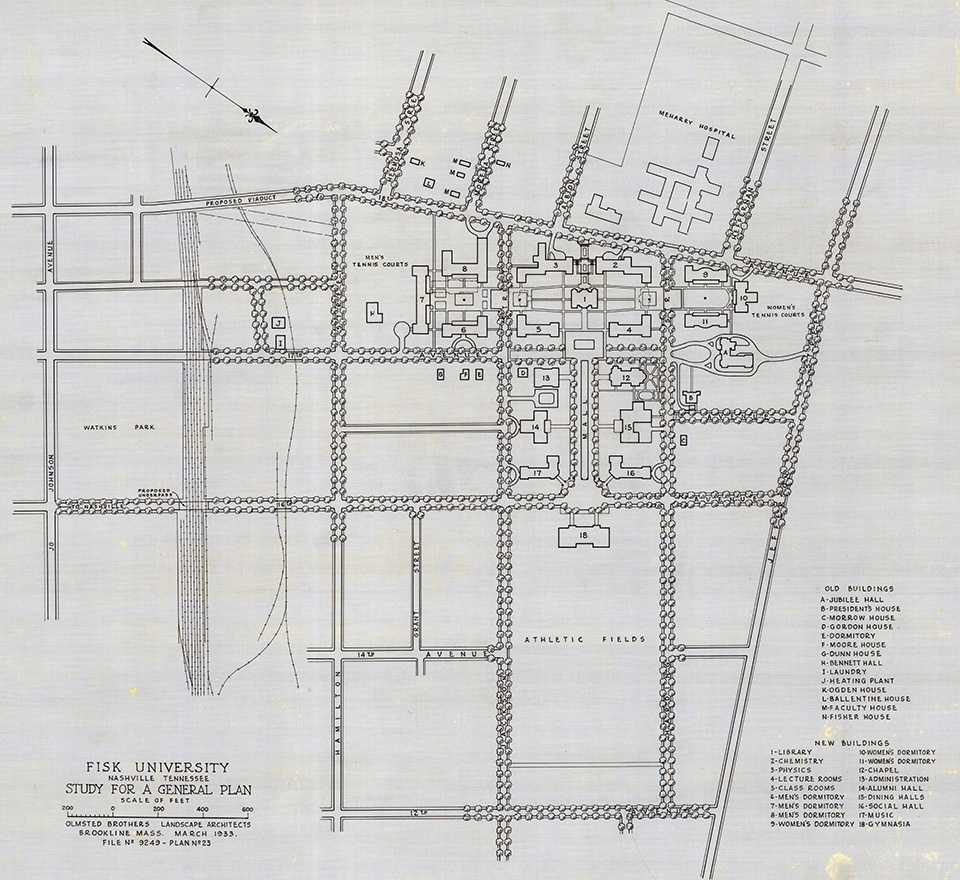

"Study for a General Plan," 1933 by Olmsted Brothers. Courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

"Study for a General Plan," 1933 by Olmsted Brothers. Courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

The following fall, students created a list of grievances, which the administration ignored. Many students boycotted classes or transferred to Howard University and other academic institutions. The breaking point finally occurred on February 4, 1925, when McKenzie delivered a chapel talk to students. Afterwards, male residents of Livingstone Hall marched through dormitories and across the grounds, singing “Before I’d be a slave, I’d be buried in my grave,” and shouting Du Bois’ name. McKenzie brought in the all-white Nashville police department, which sent nearly 80 officers to break up the “riot.” McKenzie had given the police the names of seven suspected participants who were arrested for inciting the riot - a felony in Tennessee. After it was revealed that two of those arrested had not been on campus the evening of the protest, and that the list provided by McKenzie contained the names of students who had signed a list of grievances one year prior, the judge overseeing the case dismissed the charges due to a lack of evidence. However, all the students – George Streator, R.R. Alexander, J. B. Crawford, E. L. Goodwin, Charles Lewis, Victor Perry, and Edward Taylor – were still expelled.

Fisk University Students, circa 1936. Photo by Kenneth F. Space, Courtesy National Archives.

Fisk University Students, circa 1936. Photo by Kenneth F. Space, Courtesy National Archives.

The arrest of the peacefully protesting students generated public support for the students. Five days later, more than 3,000 people attended a meeting at St. John AME Church to mediate the situation. After the meeting proved ineffective, donations to the university stagnated and the trustees stepped in. McKenzie resigned that April. Towards the end of his tenue as president, McKenzie came to an agreement with the expelled students, allowing them to receive their earned credits needed to graduate or matriculate to another institution.

The next president, Thomas Elsa Jones, rolled back McKenzie’s policies, completed the fundraising campaign, and hired several African American artists and faculty members, including landscape architect David Williston and Charles S. Johnson, who was inaugurated as the university’s first African American president in 1947.

The 1924-25 protests at Fisk University redefined the relationship between African American college students throughout the nation with paternalistic administrators who ran their respective universities. Within weeks, with similar situations, students protested at Howard University in Washington, D.C., and the following year at the Hampton Institute in Virginia. Thus, the Fisk protests had long-lasting effects on African American higher education and contributed to society’s perception of the “New Negro.”

Bronze sculpture of W. E. B. Du Bois. Photo courtesy Fisk University, 2024.

Visibility

The significance of Fisk in the history of African American education is well documented, and the campus was listed as a historic district in the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. Moreover, while the university hired landscape architect David Williston and Olmsted Brothers in the 1930s to develop a campus master plan, resulting in the present-day quadrangle design, the 40-acre campus is much as it was a century ago. Those buildings associated with the student protests are gone; Livingstone Hall burned in 1970, but its cornerstone is still located on Jackson Street in front of the northwest entrance of New Livingstone Hall. The dormitory is located across from the quadrangle, which includes a bronze sculpture of Du Bois, erected in 1982.

Although the history of these protests is captured in extensive online documentation, this information is disconnected from the physical campus landscape. No organization has taken responsibility for telling the story, and Fisk University does not mention the protests on its website.

What You Can Do to Help

While those who participated in the protests nearly a century ago are now deceased, their advocacy persists in the embodied history of the campus’ landscape and setting, and in the minds of kin keepers, from scholars to knowledgeable alum.

Contact Dr. Agenia Walker Clark, Fisk University President, and Adrienne Latham, Executive Director - Alumni Affairs, to recommend that the university organize public engagement events, and on-site and online interpretation in 2025 to commemorate the centennial anniversary of the expulsion of the students; establish a permanent commemorative feature on campus to honor the protesters and the students who were expelled (such a memorial could take the form of a “roll of honor,” as expressed by Du Bois in 1924, and might be sited on the quadrangle in view of the Du Bois sculpture), advocate for the protests to be conveyed during in-person, student led tours currently offered to prospective students, and recommend submitting an update to the 1978 National Register of Historic Places listing of the “Fisk University Historic District,” to include the protests in the statement of significance.

Dr. Agenia Walker Clark, President Fisk University

Erastus Milo Cravath Hall, 3rd Floor, 1000 17th Avenue North, Nashville, TN 37208

T: (615) 3290-8555

E: President@fisk.edu

Adrienne Latham, Executive Director Fisk University Alumni Affairs

1000 17th Avenue North, Nashville, TN 37208

T: (615) 329-8632

E: alatham@fisk.edu

-

Fisk University, Nashville, Tennessee. Photo by Robbie Jones, 2024.