Located in Chicago’s Grant Park the General John Alexander Logan Monument might be America’s only equestrian statue best known not for who sits aboard the bronze horse, but for the other men and women who boldly climbed atop. On August 28, 1968, during the Democratic National Convention, anti-Vietnam War protestors gathered in the park shouting from bullhorns at the base of the statue. The Chicago shores of Lake Michigan are remarkably flat, but the 30-foot-tall statue of Logan, raising a flag high, stands on a modest hillock, the perfect ad hoc stage for an iconic political moment. The ensuing clash with Chicago police turned a park, intended to honor Union Civil War heroes into a site of mixed legacy, now remembered as ground zero for anti-war discord.

History

U.S. Civil War historian Gary Ecelbarger once described Logan as "the most important person from the nineteenth century completely forgotten in [the twentieth]."

A native of Murphysboro, Illinois, Logan was elected to the statehouse while still in his twenties and pushed through a law preventing free African Americans from entering the state. Once elected to Congress, Logan remained pro-slavery, but he prioritized preserving the Union over his personal views. By the Civil War’s end, Logan was hailed as one of the few politicians to distinguish himself on the battlefield. His views on Civil Rights also evolved: as a Reconstruction-era U.S. senator, Logan made an early push for women’s suffrage and voted for Constitutional amendments that abolished slavery and granted citizenship and voting rights to African Americans. He also founded Memorial Day (originally called Decoration Day) with the goal of honoring fallen Union soldiers, so that those who fought for the North could be honored just as he saw Southerners begin to lionize their own dead.

Within months of his own death in 1886, the Illinois State legislature appropriated $50,000 for a Logan memorial in Chicago and commissioned leading late nineteenth-century designers: architect Stanford White (base and surroundings); sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens (Logan); and sculptor Alexander Phimister Proctor (Logan’s horse, Slasher).

As many as 500,000 people attended the July 1897 monument unveiling at what was then known as Lake Park. A Chicago Tribune reporter spared no melodrama describing the monument. Logan, he wrote, is depicted “with the hero’s courage that overrides all obstacles. … His head is bared, his hair tossed back, the silken folds of the heavy flag seem almost to rustle into actual sound and the snorting of the responsive steed to echo in your ears as you look upon the statue.”

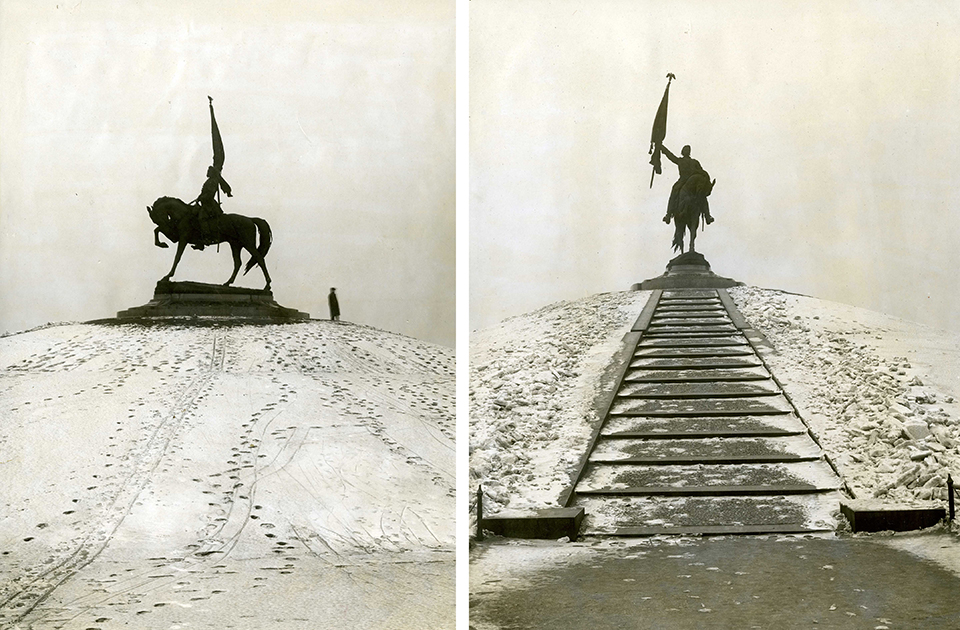

Photos of the Logan Monument Provided to Olmsted Brothers by Chicago park Commission, 1908. Courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Photos of the Logan Monument Provided to Olmsted Brothers by Chicago park Commission, 1908. Courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Perhaps in keeping with Ecelbarger’s assertion that Logan’s memory faded in the twentieth century, Lake Park was renamed for Ulysses S. Grant in 1901. It was around that time that the park’s formal, parterre landscape was redesigned by Edward H. Bennett. By the 1960s, the park numbered 319 acres near the lakefront, stretching from Randolph Drive and the Chicago River to the north, and to McFetridge Drive on the south. The Field Museum of Natural History, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Shedd Aquarium all became park landmarks and tourist attractions.

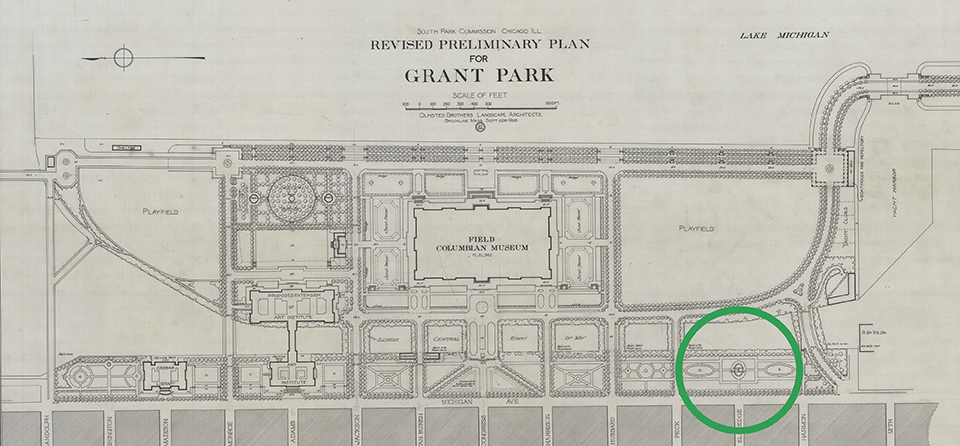

Revised Preliminary Plan for Grant Park Showing Location of Logan Monument, Olmsted Brothers, 1903. Courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Revised Preliminary Plan for Grant Park Showing Location of Logan Monument, Olmsted Brothers, 1903. Courtesy of the United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Grant Park was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1993. The nomination defines the period of significance as 1892 to 1942 and the monument as a contributing feature. Of note, the nomination’s narrative text states that the park “has been the site of a number of important public demonstrations through which people have demanded social change between the late 1960s and recent years."

Chicago was selected to host the 1968 Democratic National Convention (DNC) and the metropolis, like other cities across the nation at this time, was the site of considerable social unrest. Fires had burned on the West Side after the April assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the June murder of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., the leading anti-war candidate, set the stage for a contested convention. Activist groups including the Yippies (the Youth International Party), the Poor People’s Campaign, and the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam all converged on Chicago in hopes of pressuring the Democrats to support pulling out of Vietnam.

Grant Park during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Photo by Bea A Corson.

Grant Park during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Photo by Bea A Corson.

Mayor Richard J. Daley was determined to maintain order at all costs and would not allow the protestors to march. Instead, they were granted a permit to gather at Grant Park, two blocks south of the Conrad Hilton where many delegates and journalists were staying. Protestors had thrown stink bombs into hotel lobbies, and law enforcement took seriously a rumor that they also planned to contaminate Chicago’s water supply with LSD.

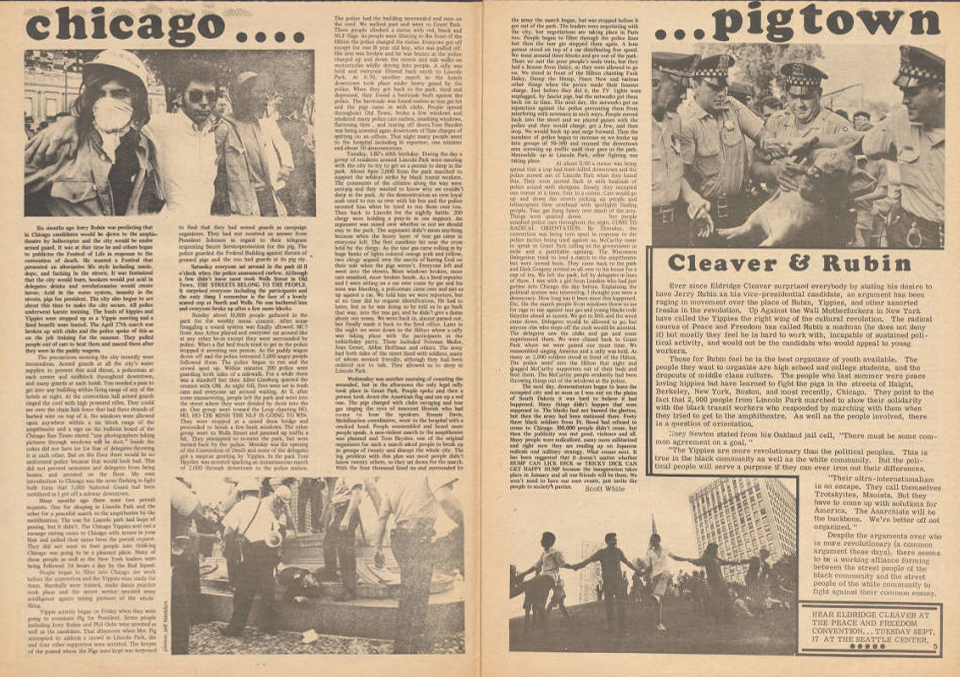

Article in Helix newspaper showing protestors at the Logan Monument (lower left), 1968, Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Article in Helix newspaper showing protestors at the Logan Monument (lower left), 1968, Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Minor skirmishes took place on August 26. Daley complained that protestors were sleeping in the parks and by August 28, national guardsman and Chicago police lined the park boundaries. Officers reported being hit with bottles and bags of human feces. Around three p.m., the Democrats voted against making opposing the war an official party position. Hours later, Daley followed-up with a resolution of his own to clear an estimated 15,000 protestors from Grant Park.

Canadian-American activist Judy Gumbo, an early member of the Yippies, recalled that, “the sight of the cops coming into Grant Park with their batons, slapping them against their sides and marching in, really roughing people up, doing terrible stuff to people, was an amazing sight. It was scary, but I don’t remember the scary as much as I remember the empowerment. The feeling of, ‘We are doing the right thing.’”

Nearly 8,000 protestors flowed north on Michigan Avenue towards the Hilton and became trapped by Chicago police officers. “The Battle of Michigan Avenue,” as the clash was called, left officers, protestors, journalists and trapped political aids injured. Eugene McCarthy, the failed Democratic anti-war candidate, set up an emergency medical station on the fifteenth floor of the Hilton. Among the countless injuries: One young man whose arm was broken when cops pried him from Slasher’s back.

Grant Park, Chicago, IL. Photo by Scott Shigley, 2024.

Visibility

The 1968 protests at Grant Park and its surroundings are well documented through photography, eyewitness accounts, news coverage, documentaries and narrative films. Hunter S. Thompson and Norman Mailer were among the writers who witnessed the Battle of Michigan Avenue. “The military spine of a great liberal party had finally separated itself from its skin,” Mailer would later write. “It opened the specter of what it might mean for the police to take over society.”

The memories and images of that convention have been on the minds of many during 2024, when a new generation gathered to protested America’s role in an overseas conflict. In advance of the 2024 DNC, The New York Times compiled an oral history of that inflammatory August in 1968.

Yet despite the preponderance of available documentation, no interpretive markers in the park today commemorates the 1968 protests and subsequent police violence. Similarly, the Chicago Park District’s website fails to mention the pivotal role the monument and hillock played during the protest.

In 2021, in the aftermath of Black Lives Matter protestors attempting to topple a Grant Park statue of Christopher Columbus, former Mayor Lori Lightfoot launched the Chicago Monuments Project, “to grapple with the often unacknowledged — or forgotten — history associated with the city’s various municipal art collections and provides a vehicle to address the hard truths of Chicago’s racial history, confront the ways in which that history has and has not been memorialized, and develop a framework for marking public space that elevates new ways to memorialize Chicago’s history more equitably and accurately.”

A preliminary report identified 41 murals, plaques and sculptural works, including the Logan Monument, that should have their place and purpose in the city re-evaluated. Subsequent recommendations placed the Logan Monument on a list of famous men whose memorials were “not prioritized for immediate artistic interventions,” but were in need of revised “accompanying texts.” The city says it will “continue to engage community members” in conversation about the monuments to Logan, Leif Ericson, Benjamin Franklin and other historic figures.

What You Can Do to Help

Contact Chicago Park District’s General Superintendent & Chief Executive Officer, Rosa Escareño, to recommend increasing the visibility of the 1968 protest through on-site and online interpretation; and updating the National Register of Historic Places nomination to expand the period of significance to include the protests.

Rosa Escareño

Chicago Park District

4830 S. Western Ave. Chicago, IL 60609

T: (312) 742-7529

E: Superintendent.Escareno@chicagoparkdistrict.com

Complete the Chicago Monuments Project online form to recommend increased visibility of the role the Logan Memorial played in the 1968 protest, through on-site interpretation or commemorative gestures.

-

Photo by Scott Shigley, 2024.