A three-acre site in Boston’s South End was the center of a major four-day protest in April 1968 against the urban renewal plans of the Boston Redevelopment Authority, which had forcibly displaced residents and demolished 68 homes, a community center, and two parks in the area. Civil rights leader Melvin H. “Mel” King and other activists established a “tent city” that was briefly home to more than 400 protesters. Twenty years after the protest in 1988, an alliance of non-profit developers, the Tent City Corporation, opened the 269-unit mixed-income housing development called Tent City, named for the historic demonstration.

History

April 1968 was a time of turmoil in America. The assassination of Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4 unleashed a torrent of emotions across the country. Feelings of anger, disillusionment, and grief prompted thousands to take to the streets in American cities, rioting and protesting in response to Dr. King’s death. In Boston, where Martin Luther King, Jr., had spent many years as a doctoral student at Boston University, James Brown staged a concert the day following the assassination to help avert widespread violence. Brown, Mayor Kevin White, and Councilor Tom Atkins addressed the crowd together, calling for peace. Regardless, tensions simmered.

Even before Dr. King’s death, Boston was amid a transformation. In the early twentieth century, a growing industrial economy and the Second Great Migration attracted African American, Latino, and Caribbean families to the city’s South End neighborhood. Originally an expanse of uninhabitable tidal marsh surrounding the urbanized peninsula of Boston, the South End was progressively infilled and developed through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The community became typified by broad commercial avenues and gridded residential streets lined by brick rowhouses in the Queen Anne, Renaissance Revival, Greek Revival, and Italianate styles. Wealthy residents quickly acquired the finest homes, organized around leafy green squares, while middle class families moved into subdivided rowhouse apartments. Tenements and lodging houses sited furthest from the neighborhood’s parks welcomed the city’s rapidly growing industrial workforce. As the neighborhood grew and diversified in the twentieth century, a community of middle-class African American residents flourished. African American businesses, churches, and entertainment venues prospered in South End, and the Boston Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sited its first headquarters at the corner of Massachusetts and Columbus Avenues. But following the 1934 passage of the National Housing Act, legally-enforced social and economic redlining diverted resources from this diverse corner of the city.

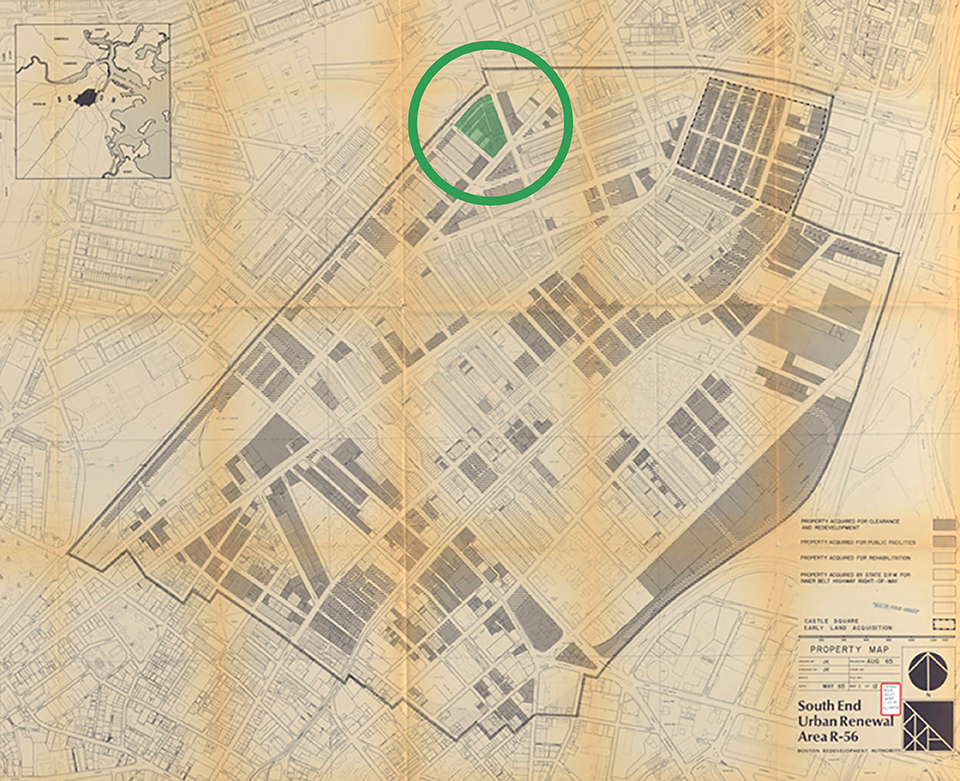

In 1957, the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) was established to oversee all city planning and development, and the South End became one of its first areas of focus. Two years later, they announced the first of a series of plans for sweeping demolitions across the South End, a process nominally intended to rid the city of blight and make way for new commercial development, but which effectively displaced thousands of families, primarily African American. Community backlash was immediate, but the BRA proved to be a powerful opponent. Melvin H. “Mel” King, a local activist, founded the Community Alliance for a Unified South End (CAUSE) in 1967 to organize residents facing displacement.

"South End Urban Renewal Area" showing "Property Acquired for Redevelopment" by Boston Redevelopment Authority, August 1965. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center.

"South End Urban Renewal Area" showing "Property Acquired for Redevelopment" by Boston Redevelopment Authority, August 1965. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center.

Against this backdrop of national unrest and local opposition, in April of 1968 the BRA carried out the demolition of a block at the corner of Columbus and Dartmouth Avenues containing 68 single- and multi-family rowhouses, a community center, and two parks, and announced that a parking garage would be developed on the site. As was the case with previous BRA projects, numerous families were displaced without relocation. On Thursday, April 25, CAUSE organized a sit-in at the offices of the BRA, and over the next 24 hours, staged a plan to peacefully occupy the lot at Columbus and Dartmouth to raise awareness about the need for affordable housing.

Tent City: A Place for People

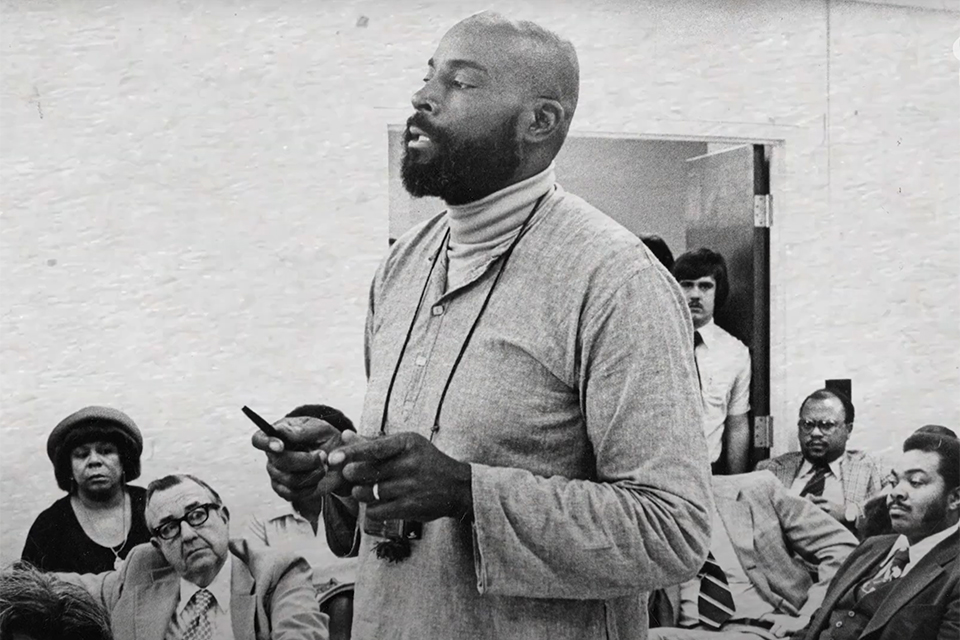

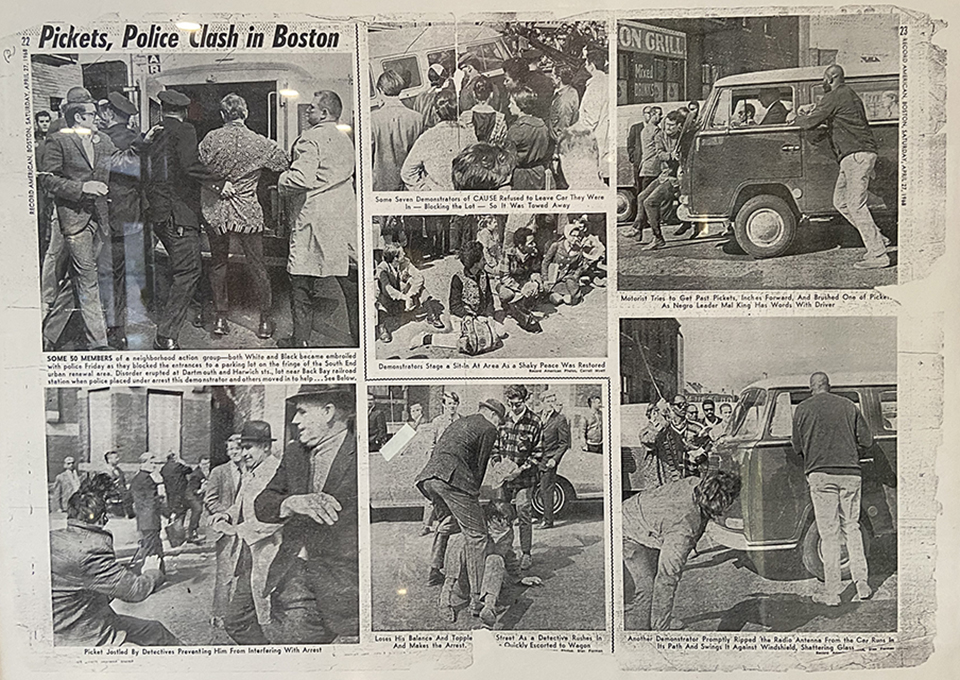

By the morning of Friday, April 26, King and a group of activists reclaimed the lot as “a place for people.” Resistance was swift: King was struck by a counter-protestor driving a Volkswagen bus, which led to an outbreak of fighting. Law enforcement arrested 23 protestors, but soon released them on their own recognizance, with some officers even expressing support for King’s efforts. Undaunted, the demonstrators returned to the site and were soon joined by crowds of supporters.

Tent City, 1968. Photo by Bill Chaplis. Courtesy of Associated Press.

Tent City, 1968. Photo by Bill Chaplis. Courtesy of Associated Press.

Over the next three days, hundreds of people gathered at what came to be called, “Tent City,” so named for the tented and wooden shanty houses erected on site. Design and engineering students from Boston’s many research institutions, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard University, and Tufts University, helped organize and build the encampment’s makeshift houses, gathering spaces, and community kitchens. Occupants embraced the title and installed signs welcoming members of the media to their “city.” The atmosphere was festive and peaceful. Musicians played and the noted Boston Celtic, Bill Russell, supplied protestors food from his nearby restaurant, Slade’s Bar & Grill. The energy, tenacity, and unity of the protest attracted national media coverage and drew attention to the racially discriminatory redevelopment practices in Boston. Police continuously ordered the protestors to vacate the site, and on April 30th, the demonstrators complied. Public support engendered by the protestors pressured the BRA to reconsider their plans. Additionally, the Episcopal Diocese donated $10,000 to CAUSE, empowering King to continue his advocacy efforts.

Newspaper clippings displayed in the lobby of Tent City Apartments. Photo by Charles A. Birnbaum, 2024.

Visibility

Armed with public, institutional, and financial support, King formed the Tent City Task Force in 1969, which over the next decade became a community-led development organization focused on providing affordable housing and protecting the diverse, multi-racial, character of Boston’s South End. The Task Force ultimately became a non-profit development alliance known as Tent City Corporation, and in 1988, twenty years following the protests, the group opened a 269-unit mixed-income housing development designed by architects, Goody Clancy & Associates and landscape architects, Halvorson Company. Its name, Tent City, honors the historic demonstration.

Mel King has been the focus of several oral histories and his activism has been noted by many. Civil rights leader and activist Jane Edmonds cites King as setting the paradigm for place-based activism. Edmonds discusses King’s influence, and the importance of the Tent City protests in her inspiring and deeply personal keynote address (above) at TCLF’s Oberlander Prize Forum II: “Landscape Activism” in 2022 (see 7:18-15:20). She acknowledges that while “Mel’s movement was not successful, not in the way that he immediately wished, that black people would retain their homes…he was successful in other ways; one that directly benefited ‘yours truly’ in a gesture of what we now call allyship.” In November 2021 the city honored King, renaming the intersection immediately south of Tent City (Yarmouth Street and Columbus Avenue), Melvin H. “Mel” King Square.

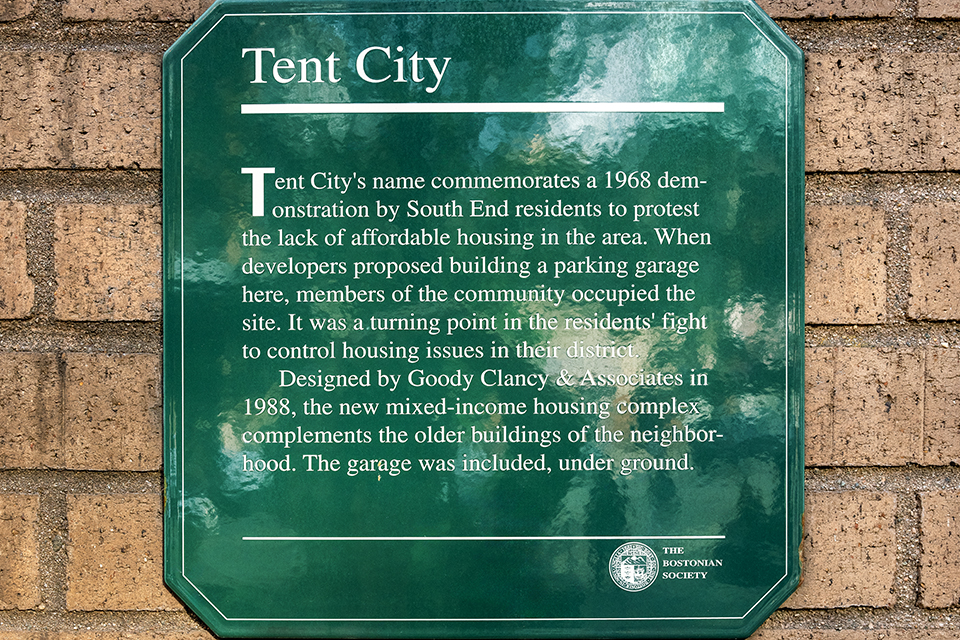

Despite King’s import and Tent City’s historic, cultural, and geographic significance, public interpretation on or near the site is scant. While a small plaque prepared by the Bostonian Society hangs at the community’s western entrance, its text downplays the political and social context of the demonstration. Similarly, a panel located in a plaza immediately north of the complex explains the area’s history of expansion and economic development but does not acknowledge urban renewal plans and the subsequent advocacy efforts.

Tent City’s common areas reflect a shared appreciation for the people and events that led to its creation. In the lobby, Mel King and Tent City Corporation founder Ena Harris are memorialized in framed interpretive panels and newspaper clippings, and the prevailing spirit of community participation is evidenced by the ubiquity of noticeboards sharing events, celebrations, and activities by and for residents. Nonetheless, the ‘Tent City Apartments’ website fails to recognize the history of the complex, including the advocacy efforts that led to its creation.

Layers of local and national significance overlay the cultural landscape of Tent City. The apartment complex is located within the boundaries of the 238-acre South End Historic District, which was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. The nomination, which focuses on the district’s architectural significance, considers only the district’s nineteenth century period, ignoring its early and mid-twentieth century development and historically significant events.

What You Can Do to Help

There is an opportunity to further amplify King’s significance through on-site interpretation and physical commemorative gestures, which could include a sculpture or permanent streetscape mural, following the precedent of Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington, D.C.

Complete the Boston Arts Commission online form to recommend the addition of a sculpture or streetscape mural in commemoration of the 1968 protest.

While organized by King, Tent City represents the efforts and voices of “hundreds of black Bostonians and thousands of supporters,” as Edmonds notes. These voices, and the recollections of Tent City associated with each, could be preserved through oral histories, just as King’s have. As such knowledge keepers pass on, their stories are at risk from fading from public memory.

The South End Historical Society is currently producing an oral history project intended to capture the “history of Boston’s South End during a period of rapid social and cultural change, often characterized as ‘gentrification,’ from the 1960s through the 1980s.

Contact the South End Historical Society, to share personal stories of the Tent City protests and recommend updating the National Register of Historic Places nomination to expand the period of significance of the South End Historic District beyond 1900 to include significant twentieth-century historic events (including the 1968 demonstration).

South End Historical Society

532 Massachusetts Avenue, Boston, MA, 02118

T: (617)-536-4445

E: Admin@SouthEndHistoricalSociety.org

-

Photo by Millicent Harvey, 2024.