This ten-acre public space located in the heart of Greenwich Village, New York City, has hosted numerous notable protests since it was designated a public park in 1827. Its first public use was as a military parade ground, and in 1911, a procession to commemorate the devastating Triangle Shirtwaist Fire (which had occurred just one block east of Washington Square Park) proceeded through the landscape, followed by a rally for better working conditions attended by 20,000 workers the following year. A proposed redesign of the park by Robert Moses in 1935 would have routed a major roadway through its center, forever altering the relationship between the public space and its value as a common green. Over 23 years, community members defeated every proposal Moses made in a grassroots movement that inspired historic preservation efforts throughout the city. Organizations like the Joint Emergency Committee to Close Washington Square Park to All But Emergency Traffic (JEC), led by famed civic advocate Jane Jacobs and others, successfully made the case for prioritizing the lived experience of the neighborhood residents over traffic flow, eventually leading to the redesign of the park by nine local architects and permanent removal of all vehicular traffic from the park.

History

Following the founding of New Amsterdam in 1624, Dutch settlers displaced the Lenape population residing near Minetta Creek, located in present day Greenwich Village. In 1629 the future Director of New Netherland, Wouter van Twiller, established a tobacco plantation on the island, which was dependent on enslaved Africans. In 1644 the company granted eleven enslaved men their freedom, provided that their children would remain enslaved. These “half-freed” men were afforded land grants in lower Manhattan and became independent farmers. They established a close-knit community that thrived until the late eighteenth century when, under English rule, their properties were seized and absorbed into surrounding estates.

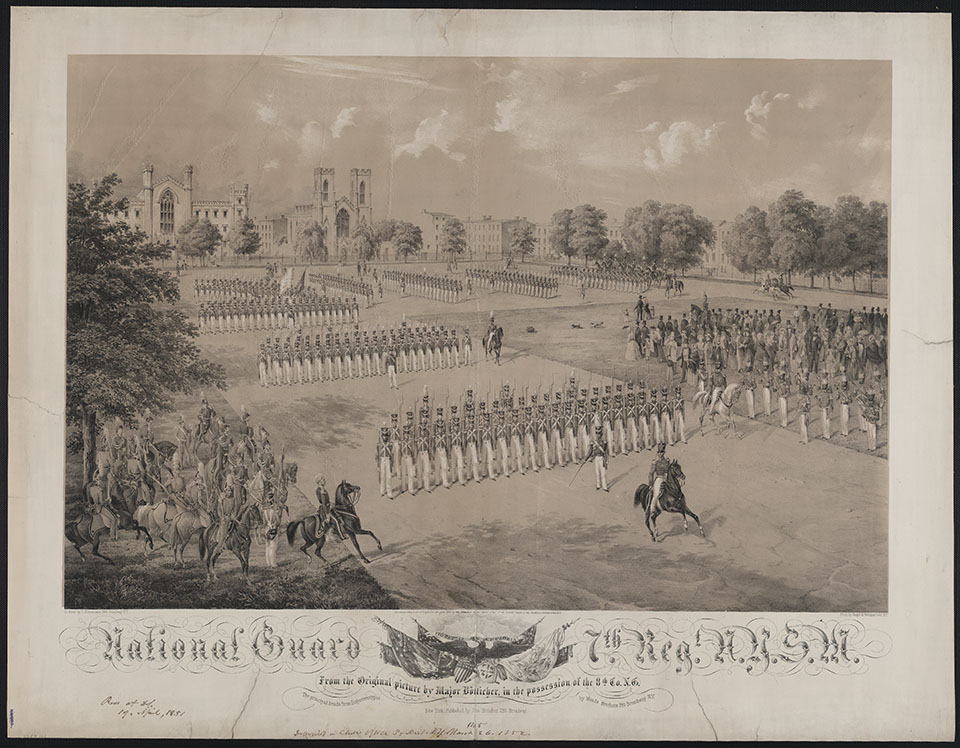

In 1797 the City’s Common Council acquired 9.75 acres of this land to establish a burial ground for unknown or indigent people. This “potter’s field” operated for nearly 30 years until it reached capacity due to the yellow fever pandemic. Shortly thereafter, Mayor Philip Hone planned to convert the space into a public park as part of an effort to raise surrounding property values. In 1826 the site served as the Washington Military Parade Ground, marking the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

Washington Military Parade Ground, ca. 1852. Charles Gildemeister. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Washington Military Parade Ground, ca. 1852. Charles Gildemeister. Courtesy Library of Congress.

The following year, now known as “Washington Square,” it was declared a “public space” and attracted prominent families to the area, specifically to the north side of the park, where rows of Greek Revival style homes had been built for people fleeing the unsanitary urban conditions further south as the city, previously concentrated in the southern tip of the island, began to develop northward.

After the establishment of the city’s Department of Public Parks in 1870, the site was redesigned by Montgomery Kellogg and Ignatz Pilat, (the latter formerly served as Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr.’s chief landscape gardener for Central Park). Their design featured curvilinear paths, lawns interspersed with shade trees, and a carriage drive that entering from Fifth Avenue, which aligns with the landscape’s center. In 1895 the Fifth Avenue entrance was distinguished by the addition of the marble Washington Square Arch, designed by architect Stanford White. White coordinated with Calvert Vaux and Samuel Parsons who at the time served with the city’s Department of Public Parks.

Washington Square Park, 1936. Courtesy New York Public Library.

Washington Square Park, 1936. Courtesy New York Public Library.

With the arch as its focal point, the park’s location at the terminus of Fifth Avenue, one of New York’s most important thoroughfares, has made it an ideal location for demonstrations. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century the park hosted a variety of protests, including several advocating for women’s and labor rights.

Even after sustaining heavy use and deferred maintenance during the Great Depression, the park remained a popular community gathering space, with many events related to federally funded programs designed to lift morale and employ artists. The election of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia in 1934 ushered in a new era for the N.Y.C. Parks Department with a surge in public investment. Appointed as the Parks Commissioner, Robert Moses planned from the onset to redesign the park. Three separate extreme proposals unveiled between 1935 and 1952 spurred residents to develop their protest tactics and perfect their strategy. The first proposal in 1935 aimed to reroute traffic from the park onto a one-way circular drive around it, necessitating widening the encircling streets and forcing pedestrians to cross a wide stream of vehicular traffic to access the park. The proposal also included a formal landscape plan, which meant removing many of the park’s significant trees. Although the proposal was accepted by the Washington Square Association, one of the city’s best-established neighborhood groups, by 1939 significant opposition led to the formation of a coalition, the Volunteer Committee for the Improvement for Washington Square. After the start of World War II, the press reported that the plan had been “postponed indefinitely.”

In 1947, Moses reemerged with a new plan which rerouted traffic around the park, removed the fountain, and added a “turn-out” area in the park’s center that would accommodate up to ten buses at a time. As community opposition strengthened, Moses continued to revise his plan, in 1952 announcing a redesign that would construct two 38-foot-wide roads through the park. Horrified, two Greenwich Village residents, Shirley Hayes and Edith Lyons, organized the Washington Square Park Committee. After they successfully gathered 4,000 signatures in a petition to stop the plan, the New York City Board of Estimate decided not to move forward.

Undeterred by the setback, Moses continued to press for his design. Motivated by increasing real estate values, he advanced for another of his roadway plans: the Lower Manhattan Expressway. As Moses continued to imagine new ways to leverage the park to accommodate ever-increasing traffic, Hayes and Lyons coordinated with other influential nearby residents, including Ray Rubinow, Jane Jacobs, Eleanor Roosevelt, Margaret Mead, and Lewis Mumford, and Ray Rubinow, to form the Joint Emergency Committee to Close Washington Square Park to All But Emergency Traffic (JEC), which became one of the earliest intentional historic preservation efforts in New York City, several years before the infamous demolition of Penn Station became the precipitating even that led to the establishment of the Landmarks Preservation Commission. As they discussed how to move forward, Jane Jacobs suggested that they request a temporary closure of the park to cars, to allow the city to test its impact before making any permanent decisions.

The Village Voice, 1956. Courtesy New York Public Library.

The Village Voice, 1956. Courtesy New York Public Library.

After one final presentation, the Board of Estimate voted to temporarily close the park to all but emergency traffic on October 23, 1958. In April of the following year, the Board of Estimate approved making the change permanent. By 1963, the positive impact of that decision was clear, as it had both improved traffic in the surrounding neighborhood, in direct contrast to the assertions of Moses, and provided a truly green space for residents of a neighborhood that was otherwise significantly lacking in such an amenity. The Board of Estimate proceeded with the legal process of permanently closing the park to all traffic. By advocating for the park over six years, the JEC had ensured it would remain intact, preserving it for future generations to use.

The Last Car Through Washington Square, 1958. Photo by Claire Tankel, Courtesy Village Preservation.

The Last Car Through Washington Square, 1958. Photo by Claire Tankel, Courtesy Village Preservation.

Today the park remains dedicated to pedestrian use and functions as the heart of protest culture in the city.

Photo by Barrett Doherty, 2024.

Visibility

After achieving their initial goal of temporarily closing the park to traffic, advocates immediately turned their attention to imagining how the park would look and function without vehicles. Even with the temporary closure, Gilmore Clarke, a prominent landscape architect who had been hired to work on the park and Newbold Morris, who had replaced Robert Moses as Parks Commissioner in 1960, proposed a design that centered around the construction of a road through the park. In response, nine members of JEC, who were also local architects, developed and proposed plans that were incorporated into a plan prepared by local Manhattan Community Board No. 2. Their vision offered an alternative future for the neighborhood and relied on the permanent closure of the road through the park to create an unbroken promenade around the perimeter and included the addition of new sculptures and plantings. The plan was also $250,000 less expensive than the plan proposed by Clarke and Morris, and on October 27, 1964, it was accepted by the mayor.

After the rehabilitation of the park in 1970, the JEC finally disbanded, but maintained ties within the community. In the oral history documented by Village Preservation, Edith Lyons (92 at the time of the recording), who Ray Rubinow once hailed as “The Mother of Washington Square,” stated, “It was one of the great privileges of my life to have led this wonderful preservation effort from beginning to end.”

For almost 50 years, the design of Washington Square Park was a testament to both the advocacy of the JEC and the investment of the community, including those nine village architects, who envisioned how closing Washington Square Park to cars would ensure that what they loved most about the space would still be there for future generations. Each rehabilitation of the park protected the arch and several trees, including a mature English elm, which remain as silent witnesses of the fight to remove cars from Washington Square Park. In 2014 the park underwent a controversial rehabilitation by Parks Department landscape architect George Vellonakis, which included a substantial layout change to move the fountain to align it with the arch. As the new focal point of the park, the fountain was rebuilt in a level central plaza, altering one of the most beloved versions of the 1970 design: a sunken plaza ringed by shade trees.

Enjoying the steps around the fountain, ca. 1980. Courtesy Village Preservation.

Enjoying the steps around the fountain, ca. 1980. Courtesy Village Preservation.

Like the Battle of Central Park, where a group of determined mothers had protested the destruction of a wooded glen where their children played for the construction of a parking lot, the community members who advocated for Washington Square Park eventually saw even better results than they had set out to achieve. In both cases, the increased attention they drew to what they considered the heart of their community eventually produced substantial improvements to the places they were fighting for and strengthened the ties throughout the community. Organizations, including Village Preservation and The New York Preservation Archive Project, feature extensive information about the movement to “Save the Square” on their websites, and the N.Y.C. Parks Department devotes a webpage outlining the movement. The information conveyed on the N.Y.C. Parks Department website is echoed by an on-site interpretive marker titled, “Shirley Hayes and the preservation of Washington Square Park.”

What You Can Do to Help

Become a member of Village Preservation, the non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the architectural heritage and cultural history of Greenwich Village, the East Village and NoHo, to support their efforts to document and illuminate the important history of Washington Square Park via oral histories, ongoing research and advocacy, and free public programming. For more information and ways to get involved with Village Preservation, contact them at info@villagepreservation.org. You can also email any member of their staff directly via this page: https://www.villagepreservation.org/about-us/our-team/

Volunteer for the Washington Square Park Conservancy, to “help keep Washington Square Park clean, safe and beautiful.” In addition to significant volunteering efforts that maintain the park as a vibrant community space, the Conservancy puts on numerous events to continue the landscape’s long history as a place of community gathering. You can also contact their staff at: hello@washingtonsqpark.org

Contact Jonathan Kuhn, Director of Art and Antiquities at N.Y.C. Department of Parks and Recreation, to recommend the installation of additional interpretive markers at Washington Square Park and increased interpretation online.

Jonathan Kuhn, Director of Art & Antiquities

New York City Department of Parks and Recreation

The Arsenal, Central Park

830 5th Ave. Room 203, New York, NY, 10065

T: (212) 360-3410

E: artandantiquities@parks.nyc.gov

-

Photo by Barrett Doherty, 2024.