The Italian Garden at Queset

Abandoned for generations, this ruined garden is a silent testament to Edwardian-era bon vivants and the Golden Age of American gardens.

The Italian Garden at Queset is much like a family heirloom found in the attic—magnificent but a bit tarnished. Abandoned for generations, this ruined garden is a silent testament to Edwardarian-era bon vivants and a golden age in American gardening. Though many historic designed landscapes of this era have been lost, this classically inspired garden has survived albeit largely forgotten under a choking tangle of vines and brambles. Preservation efforts are underway and it is now being restored, a Renaissance revival for a Renaissance garden.

Winthrop Ames (1870 -1937), scion of a wealthy manufacturing family, was the designer of the Italian Garden at his family’s country seat in North Easton, Massachusetts. The Queset estate – named for the stream that runs through the property – was established in 1852 by Winthrop’s father, Oakes Angier Ames. He built the original manse, a handsome Gothic Revival residence attributed to Andrew Jackson Downing. The Ames family had lived in this area since the late 18th century, earning their livelihood as blacksmiths and manufacturers. By the 19th century, they had made their first fortune manufacturing shovels, supplying nearly 60% of the shovels used worldwide by the late 19th century. Skillfully parlaying their newfound wealth, the Ames family capitalized the nation’s first transcontinental railroad, the Union Pacific, thus making their second fortune as railroad barons.

The Ames children pose with the family dog in

the Italian Garden.

Like the Medici of Renaissance Italy, the Ames became seminal figures in politics and the arts. In the political realm, Oakes Ames served in Congress. His brother, Oliver Ames, served as governor. As patrons of the arts, they commissioned the noted architect Henry Hobson Richardson and landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., for the numerous public buildings, monuments, and private estates that they built in North Easton.

Having little interest in the family business, Winthrop studied art and architecture at Harvard University and lived abroad for many years. He eventually established himself in New York’s theatre world, taking full advantage of family money and his theatrical talents. He financed and built two Broadway landmarks – the Little Theatre (renamed the Helen Hayes Theatre in 1983) and the rebuilt Booth Theatre (named for actor Edwin Booth, brother of John Wilkes Booth).

Despite his career in New York, Winthrop Ames made Queset his home. He began enhancing the property with projects reflecting the taste and wealth of his generation. Ames began laying out the Italian Garden in 1911. The choice of such a formal garden can be attributed to popular trends during this period. Known as the Country Place Era, America’s moneyed elite built grand estates modeled after those in Europe. Formal garden designs inspired by Renaissance and Baroque gardens were popularized by such noted designers and arbiters of taste as Edith Wharton, Beatrix Farrand, Charles Platt, Stanford White, and Guy Lowell.

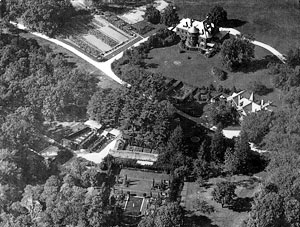

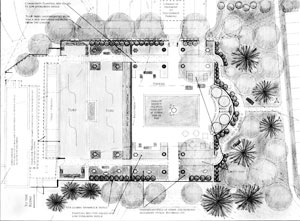

(top) Aerial view of the Queset estate with the Italian Gardens in lower

center of image. (bottom) Plan of the Italian Garden at Queset

(Courtesy: The Ames Free Library/Illustration: Kath Holland).

In an interview conducted by the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in 1930, Ames commented that Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., had once been involved with the estate and had “made some changes in the naturalistic planting about the lawns and elsewhere.” As for the design of the Italian Garden, he was rather self-deprecating:

The more formal features of the place – the [Italian] garden, the croquet lawn and the ‘yard’ – were designed (if proceeding largely by trial and error can be called design) by me; my wife supervises the flower planting, and we owe much to the interest of our superintendent, J. Fred Coles.

Winthrop deftly applied his talent for stagecraft to garden design by transforming a humble kitchen garden into a Renaissance-inspired vignette – a hortus conclusus – nestled into the woodlands and the surrounding vernal ponds. Taking advantage of a gentle slope, he designed a series of terraces and stone steps cascading from the brow of the hill to a stone columned pergola at its base. A reflecting pool featuring a cast stone Assyrian figure playing the pipes–with fountain sprays amongst iris–was a principal feature. Ames created a sense of mystery and allure – in the spirit of the Renaissance giardino segreto–by enveloping his garden with a hedge of native, Rosebay rhododendron. The verticality of columnar trees marching up the terraced hillside further emphasized the influence of Italian Renaissance gardens. Clipped bay trees in wooden caisses de Versailles tubs were strategically placed for additional dramatic effect.

Photographs of the Italian Garden from the 1920s illustrate a well-groomed and mature landscape. Posed among the clipped hedges and stone terraces, two young girls (presumably Ames’ daughters–Catherine and Joan) explore the wonders of the garden. Another image depicts the handsome, stone-columned pergola that also served as a stage for impromptu plays put on by Ames’ visiting theatre friends.

Upon retiring from the New York theater world in the early 1930s, Ames returned full-time to Queset, where he took an active interest in his gardens and played a role in the founding of the Cambridge School of Drama in 1932. It is unclear how long the garden was maintained following Winthrop Ames’ death in 1937. The Queset estate was eventually subdivided and some portions were sold by the family. Over the years, the property fell into disrepair and the Italian Garden was all but lost.

Threat

Although it is no longer threatened with obliteration, the garden still faces challenges. Appropriate restoration schemes and funding are still necessary if it is to be preserved and maintained as an historic designed landscape. Since 2006, the Ames Free Library Trustees have reclaimed “ownership” of the adjacent garden with a 99-year lease for the site. In order to expand and improve the library’s research capacity, the library will rehabilitate the outlaying historic buildings to create a campus for research and administrative facilities. With this proposed campus scenario, the Italian Garden has the potential to be an integral part of the library’s redevelopment plans. The restoration campaign for the buildings is underway, yet rehabilitation and funding plans for the garden have yet to be finalized. However, as the Italian Garden at Queset approaches its centennial in 2011, its significance as an historic designed landscape has at last been firmly established.

Get Involved

The community can get involved by joining the Friends of the Easton Public Gardens -- a grassroots group being organized to provide help with a number of public garden in the area. For membership information please contact Karen Cacciapuoti at Kcacciapuoti@gmail.com.