La Laguna Playground Threatened by Renovation

On May 16, 1965, La Laguna de San Gabriel playground opened to the public and 1,500 children swarmed over the life-size, concrete play-sculptures that Benjamin Dominguez, a concrete-artist from Mexico, had created.

On its opening day and for the past 45 years, La Laguna encapsulated the ideal in post-World War II playground design. La Laguna playground, located in what is now known as Vincent Lugo Park, fused fantasy, folk vernacular sculpture, imaginative play, and an aesthetic experience for park goers that was nearly lost in 2006. During the last three years, the Friends of La Laguna have worked to protect and preserve not just the playground but the unique and increasingly rare experience it affords children of all ages.

History

Benjamin Dominguez Following World War II, the population of San Gabriel boomed. As its neighborhoods expanded with tract homes, the city designated and planned for two municipal parks. Planning the Neighborhood, issued by the Federal Government in 1948, reads like a script for park planning in San Gabriel. The document encouraged that, “parks should be combined with school sites to save on land acquisition costs and avoid duplication of facilities.” In San Gabriel the plan for a city park originally contained playing fields and badminton courts. However, when it was determined that the park would be constructed next to an elementary school, components of the park design were changed in order to provide alternatives to the amenities already available. In piecemeal fashion, the city built two play areas for children and made plans for a Little League baseball field that would boast one of the few grass in-fields in the region. The 15-acre site was plainly known as “Municipal Park.” As Municipal Park began to take shape, the state of California published an interdisciplinary study titled, Guide for Planning Recreation Parks in California. The guide articulated a new vision for park design. Rather than simply providing a play lot for tots, the recommendations indicated that the park should provide a creative and imaginative experience for park goers.

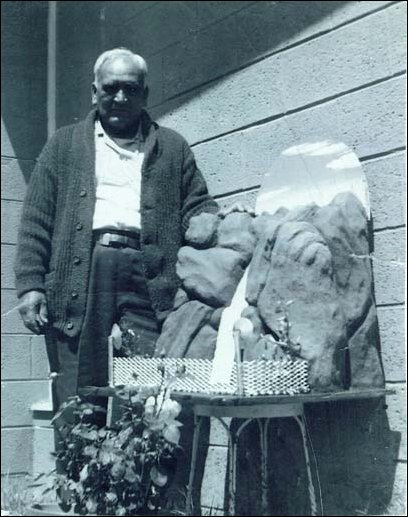

With one remaining parcel of land in Municipal Park, Parks and Recreation Director Frank Carpenter sought to create a playground that would draw new visitors and provide a new and unique landmark for the city. He stated that, “[up] to now, the success and popularity of Municipal Park has been our willingness to stretch the imagination a little and create an unusual atmosphere not found in most parks.” In November of 1963, Benjamin Dominguez presented his vision for the last remaining corner of Municipal Park to the Parks and Recreation Commission. Dominguez neither read nor spoke English. He relied on a San Gabriel resident, Vincent Lugo, to translate for him. At the end of Dominguez’s presentation, the Commission claimed that they had found the artist who would make Municipal Park an attraction for residents and the region alike.

Commissioned to create a “Fantasy Park,” Dominguez set about creating San Gabriel’s first Lagoon. Working with an amoeboid shaped space, Dominguez first designed small models in order to experiment with the manner in which the pieces would interact with each other and the space in which they were placed. He wanted to create a feeling of openness that would peak the curiosity and exploratory nature of children. He built the pieces on a “life-like” scale so that children could experience the largeness of sea creatures. At the same time, he provided places where parents could safely supervise their child’s play.

Opening Day, May 16, 1965

It took 18 months to complete the playground, and, at the age of 72, Benjamin Dominguez had created his masterpiece. He called the playground “his gift to the children of San Gabriel.” It may well be the best $12,000 the city ever spent. Three generations have now enjoyed and created memories at “Monster Park” – today, it is truly an icon for the city and has been a regional destination for families and schools alike.

Threat

Beginning in the 1970s, a heightened concern about playground injury-related lawsuits launched a new phase of playground design that advocated “no-risk” playground environments. In 1981, when the Consumer Products Safety Commission released its “Handbook for Public Playground Safety,” the fate of many mid-century playgrounds was sealed. Publically owned playgrounds and parks were remodeled, and fantasy and modernist playground elements were destroyed, making intact park playground groupings like Vincent Lugo Park’s La Laguna de San Gabriel quite rare.

In 2006, a larger park renovation called for the demolition of La Laguna Playground and its replacement with youth soccer fields. The explanation for demolition was two-fold: the playground did not conform to modern safety standards and the cost of rehabilitation was prohibitive. The community, however, refused to allow for the demolition of the iconic playground that had such deeply personal associations and provided such a unique play experience. Within three months, the city entered into a memorandum of understating with the Friends of La Laguna (FoLL) to preserve the playground.

Over the last three years, with preservation as the goal, the FoLL have commissioned an in-depth study of the playground and generated an award-winning Historic Structure Report and Preservation Plan. The playground was successfully nominated to the California Register of Historic Places and as a local landmark. Currently, FoLL is working to cross-reference the Playground Health and Safety Code with the California Historic Building Code. Playgrounds certainly fall within the category of a historic designed landscape, however, general awareness and knowledge of this attribution is lagging. Most communities do not consider a 1960s playground through the lens of historic and/or cultural value, rather it is simply a place where generations have played.

Referencing this possibility in the playground health and safety code is a first step toward broader awareness. In California, Assembly Member Mike Eng is currently introducing legislation to this effect with AB 2701. The hope of FoLL is that the bill, if successful, will provide direction on two matters: first, it will clarify that the jurisdiction of the Historic Building Code extends to playgrounds once they have achieved designation at the local, state or Federal level. Second, it will indicate that demolition is not the sole fate for playgrounds created prior to the advent of modern safety standards.

Get Involved

Supporters can send a letter to Assembly Member Mike Eng to express support for his legislative bill, AB 2701, which will exempt historic playgrounds from compliance with the Playground Health and Safety code, giving jurisdiction, instead, to the Historic Building Code.

|

Letters of support can be sent to: Assembly Member Mike Eng |

For more information, please contact: Senya Lubisich, |

Images courtesy Friends of La Laguna