“Simplicity of shape does not necessarily equate with simplicity of experience.”

History

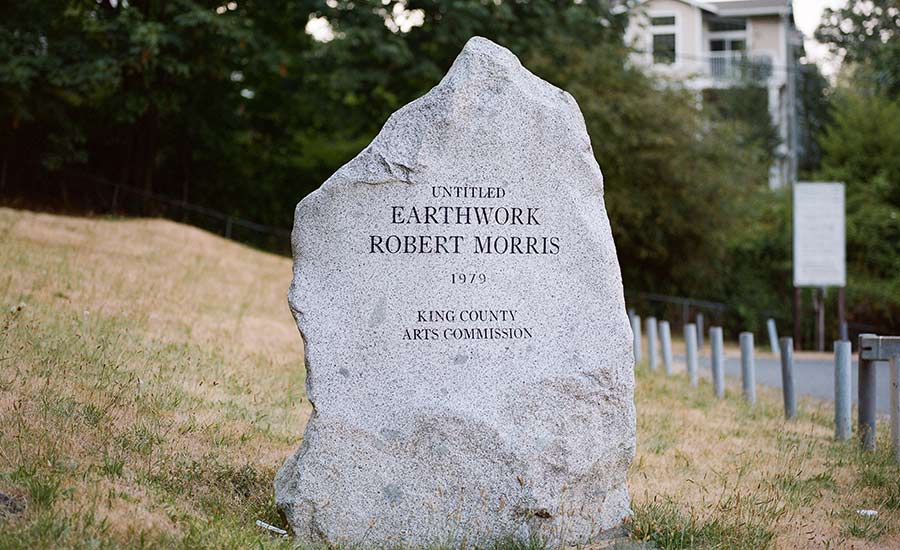

Starting in the 1960s, post-industrial and derelict landscapes including surface mines, pits, landfills, quarries, and others seen as visual and environmental blights, became in the hands of some artists provocative installations that reclaimed the land. Untitled Earthwork (Johnson Pit #30), an early monumental installation designed by the American artist, Robert Morris, is among the first land reclamation art projects in the country. Morris, an influential artist and writer, “played a central role in defining three principal artistic movements of the [1960s and 1970s]: Minimalist sculpture, Process Art, and Earthworks,”[1] according to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, which includes several of the artist’s works in its collection

Photo courtesy 4Culture

In 1978, the King County Arts Commission in Seattle, Washington engaged artists to find solutions for what the commission’s executive director Jerry Allen called the county’s “technologically abused land.” The commission held a symposium titled Earthworks: Land Reclamation as Sculpture in August 1979 that included a demonstration project.

The commission worked with the Department of Public Works (DPW), which oversaw more than 100 gravel pits, and selected the Johnson Pit (number 30 on the county’s list), declared surplus land in 1973, as a suitable site for the demonstration project. Of the 22 artists who were invited to submit proposals, eleven did so and a three-person jury selected Morris to work on Johnson Pit No. 30, which DPW donated to the county. The work was funded by a unique consortium of the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Endowment for the Arts, King County Department of Public Works, and the U.S. Bureau of Mines – the last of which had never before funded the creation of a piece of artwork. Construction of the piece began concurrent with the August 1979 symposium and was completed before year’s end. Proposals by six other artists – Iain Baxter, Richard Fleischner, Lawrence Hanson, Mary Miss, Dennis Oppenheim and Beverly Pepper – for different sites were also featured at the symposium, along with a design by Herbert Bayer, Mill Creek Canyon Earthworks, for a site in Kent, Washington.

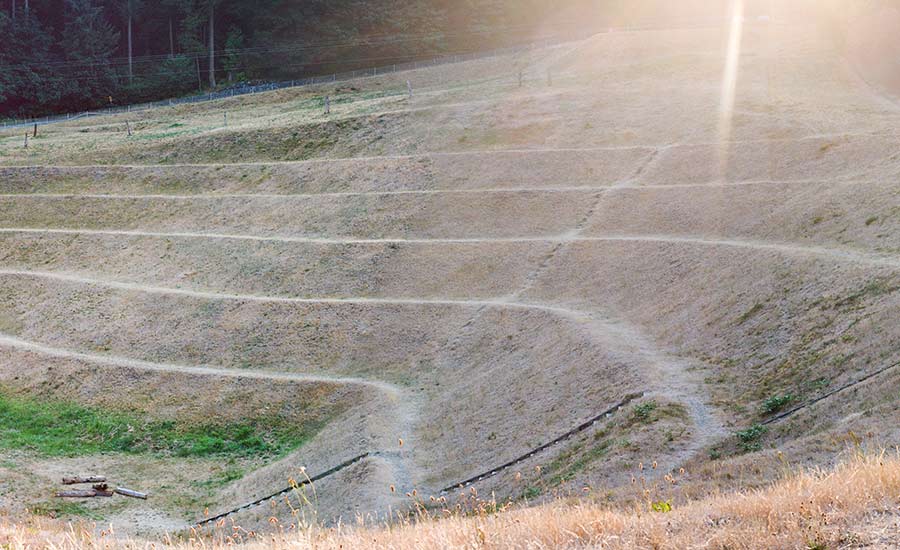

Completed in November 1979, Morris’s 3.7-acre earthwork, which is set into a hillside, consists of a series of concentric slopes planted with rye grass that descend into Johnson Pit No. 30, in the center of the site. Morris said of his proposal: “I have employed a method of terracing which has been used in ancient times as well as the present. Such a method has produced sites of such widely varying context and purpose as palaces and strip mines, highway embankments and mountainside cultivation. Persian and Mogul gardens were terraced as were the vast amphitheaters of Muyu-uray in Peru.”

To create the installation, Morris had the center of the site cleared of vegetation. Along the slope at the northwest edge of the pit, he left a line of blackened tree stumps – a symbolic “ghost forest” intended to act as a reminder of the once forested land that had been decimated by its use as a gravel pit. This became one of the most controversial and debated elements of the installation. Morris responded that it was not the artist’s job to “transform devastation into inspiration.” Morris elaborated: “It would seem that artists participating in art as land reclamation will be forced to make moral as well as aesthetic choices. There may be more choices available than either cooperative or critical stance for those who participate. But it would perhaps be a misguided assumption to suppose that artists hired to work in industrially blasted landscapes would necessarily and invariably choose to convert such sites into idyllic and reassuring places, thereby socially redeeming those who wasted the landscape in the first place.”[2]

Photo courtesy 4Culture

The premise of the Earthworks symposium and the two realized projects set a precedent, helping to redefine the country’s notion of public art at an early time in the development of government funded public art programs. At the time of the symposium, there was little legislation providing for the commissioning of public art – let alone a concept as new as land reclamation art. For those cities and counties that did have a public art program, the typical commissions were large-scale works sited in public locations, most often a plaza, city park, or government building. King County helped pioneer a new type of land-use policy through its Arts Commission by asserting that contemporary artists can and should be instrumental in envisioning solutions for civic issues, and involving them on project teams to design water, utility, infrastructure, and transit systems. This fundamental principle, that artists’ ideas can shape our built environment as well as our civic life and public policy decisions, set an early precedent for public-art programs nationally, and continues to this day through public art programs in the region.

THREAT

Photo courtesy 4Culture

The earthwork in its present form is largely as Morris created it in 1979; however, the surrounding landscape has changed considerably from agricultural land to commercial warehouses, then industrial parks, and now the site of multi-story condo and apartment developments. Throughout this time, conversations about the earthwork’s future have centered on surrendering the property to more condos and redesigning the site to include more recreational programming, such as a soccer field and picnic shelters. In 1994 the King County Arts Commission, following the recommendations of a study group it had impaneled a year earlier, began restoring the site. In consultation with Morris, a wooden pathway, constructed of reclaimed fir beams, was built leading to the basin, to direct visitors, and discourage erosion on the terraces. Wooden benches were also added and the blackened tree stumps from Morris’s “ghost forest” were replaced. Despite the restoration, ongoing maintenance remains challenging. The reclaimed fir beams chosen for the 1994 improvements have deteriorated rapidly in the Northwest climate, and are nearing the end of their life span.

The site is fenced and 4Culture, a cultural services agency created in 2003 to replace the King County Arts Commission and the County Office of Cultural Resources, hires staff to open and lock a gate to the parking area each day (at dawn and dusk). The public art program also pays for a landscaping crew to keep out invasive plants and to empty trashcans; unfortunately even with these precautions the site suffers from illegal dumping on a regular basis, and has also been a target for vandalism.

1 “Robert Morris,” Guggenheim (accessed August 21, 2014).

2 Robert Morris, Keynote address, Earthworks Symposium, University of Washington, Kane Hall, July 31, 1979.