“I hope my work provides inspiration for a person to do today what they couldn’t do yesterday, no matter what it is. That’s art ... That's the fundamental creative process and it's something that changes people and empowers them. ”

History

The Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum of Assemblage Sculpture sits on ten-acres in the Mojave Desert foothills near the Mojave National Preserve, an austere expanse of scrubby desert and jagged mountains established in 1994 as part of the California Desert Protection Act. The site holds the home, studio, and sculpture park of renowned assemblage artist Noah Purifoy (1917-2004) who lived there from 1989 until his death.

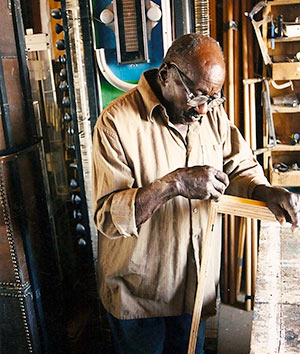

Noah Purifoy working in his studio, photo by Sue A. Welsh

Purifoy first gained acclaim for his participation in the 1966 traveling group exhibition 66 Signs of Neon, which he organized with fellow artist Judson Powell. The groundbreaking show with work by eight artists was organized in response to the August 1965 racial riots in Los Angeles’ Watts neighborhood. Purifoy, a cofounder and first director of the city’s Watts Towers Arts Center, had watched the riots from the Center’s doors and the work that he created for the show was constructed out of rubble that he salvaged in the aftermath. The experience had a profound influence on him, which he recounted in the exhibition catalogue: “Judson and I, while teaching at the Watts Towers Art Center, watched aghast the rioting, looting and burning during the August happening. And while the debris was still smoldering, we ventured into the rubble like other junkers of the community, digging and searching, but unlike others, obsessed without quite knowing why.”[1] The event marked a turning point in Purifoy’s work and fundamentally shaped his career. He viewed art as a vehicle for transformation, stating that he simply wanted to be known as an artist who made art for the sake of change and who strove to understand art and its role in the world.[2]

Originally from Alabama, Purifoy studied social work before receiving his B.F.A. at Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts) in 1956. He worked as an artist in Los Angeles for the next 30 years and was a leading figure in the Los Angeles Black Arts Movement, which began in the 1960s. In addition to his involvement in the Watts Towers Art Center, beginning in 1976, he was a founding member of the California Arts Council to which Governor Jerry Brown appointed him. In 1989 at the urging of his friend, artist Debby Brewer, whose family home and studio was in Joshua Tree, he moved his practice from Los Angeles to Brewer’s two-and-a-half-acre property in the high desert. At first the setting felt foreign to him: “I wasn’t sure I’d like the desert ... Because of the vast space and the Joshua trees, it just gives the impression of desolation and sheer poverty, actually. The earth is poor. It won’t bring forth green stuff. That’s what I miss most of all being here, since everything is brown here or beige or purple, as the case might be. But having lived here for a while … I’ve come to like it.”[3] Ultimately, Purifoy found that the desert had its advantages: “I look up less often in anticipation. What that means is that when I was in L.A. as an artist, there were a lot of comings and goings, so every little noise I’d hear – As you know, most artists are extremely sensitive to noise, because they spend quite times in their head … Here in the desert, the rabbits, the birds, the scorpions, the lizards all run quiet.”[4]

The White House (restored), photo by John Cordic

Purifoy’s work with found objects, refuse and junk was inspired by the early twentieth century French artist Marcel Duchamp, a pioneer in the use of used objects as art who created a sensation in 1917 when he submitted Fountain, a urinal he had signed, to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition (it was rejected). Duchamp was part of the Dada artistic movement, which emerged in Europe in response to the horrors of World War I, much as Purifoy’s work took shape a half-century later in response to the Watts riots.

Of found materials he said: “[W]hen new things come into being, people throw away the old things, and these are things that are oftentimes well designed. Duchamp recognized this and created the concept of ‘as is.’ … That also appealed to me in terms of junk art. It kind of trickles down from ‘as is’ to junk art, because in assemblage I try to enable the article to remain identifiable, although it’s intertwined with other objects. The more it becomes identifiable, the more interest I believe is created around the object, the complete object d’art.”[5] At his death, Purifoy had created 77 artworks and installations on the desert floor over the course of fifteen years and a total of 120 artworks were housed on the site, some made with tires, bowling balls, railroad ties, vacuum cleaners, charred wood, and old car parts.

Purifoy first began to see his property as an outdoor museum in the early 1990s, inspired by his neighbors’ interest in his work. Today the Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum of Assemblage Sculpture is overseen by the non-profit, all-volunteer Noah Purifoy Foundation, which the artist formed in 1998 with Sue Welsh, his representative and colleague for more than four decades. Each year people travel to Joshua Tree from all over the world to visit Purifoy’s home and experience his work in person. While alive the artist enjoyed meeting and interacting with visitors, especially students, and often conducted tours of the site himself and held assemblage workshops with local artists. He offered little information or explanation regarding his work, advising visitors not to look for hidden meanings, symbols, or signals.

Bessemer Steel, photo courtesy Bridget Cooks

Purifoy’s work continues to garner attention and interest from a broad array of university and independent scholars, critics and artists such as the New York-based sculptor and installation artist Andrea Zittel who created High Desert Test Sites in Joshua Tree, inspired by Purifoy’s philosophy and work, and the Los Angeles-based painter Ed Ruscha, who observed: “I’m impressed because I can see that Noah is making art that will have its own unique future. It’s not going to be packed away in warehouses; it’s going to be as he shows it.” In addition to Joshua Tree, his work is in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., among others.

William Tronzo, of the University of California, San Diego cited the Purifoy Museum in The Fragment, An Incomplete History[6] and Richard Candida Smith, an intellectual historian and Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley included extensive commentary on the Museum in The Modern Moves West: California Artists and Democratic Culture in the Twentieth Century.[7] In addition the international art publishers, Phaidon and Taschen have featured photography of the museum in their books. The recent compilation Art & Place: Site-Specific Art of the Americas noted of the artist: “The Environment, as it is commonly known, is a total work of art that fulfilled Purifoy’s lifelong mission to explore the human experience and the communicative power of art … Despite the secluded location this harsh environment does not suggest escapism or isolation, but rather the potential freedom in self-expression.”[8]

Threat

While Joshua Tree was an ideal place for Purifoy to create his work, the desert environment itself poses an ongoing threat to the sculptures. While Purifoy enjoyed how nature weathered and patinated his pieces, wind and weathering have also degraded many of the works so that they necessitate perpetual maintenance. In recent years the Foundation has undertaken sensitive refurbishment of several major works and organized annual events with community volunteers and fine artists.

Along with natural threats, the area is also home to illegal activities such as methamphetamine labs, poaching of protected animals and dumping of household trash and industrial waste. The site is ungated and there have also been incidents of vandalism and racist graffiti. While the frequency of these incidents subsided as the community embraced Purifoy’s concept, threats remain ever-present due to the openness of the site.

1 Purifoy, Noah. 66 Signs of Neon Catalogue. (Los Angeles: 66 Signs of Neon, c. 1966).

2 Noah Purifoy, informal interview with Sue Welsh, n.d.

3 African American Artists of Los Angeles: Noah Purifoy,” interview by Karen Anne Mason, 1992, transcript, 163-164, Oral History Program, Special Collections, University Library, UCLA.

4 Ibid., 164.

5 Ibid., 78-79.

6 William Tronzo, ed., The Fragment, An Incomplete History (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2009), 124.

7 Richard Candida Smith, The Modern Moves West: California Artists and Democratic Culture in the Twentieth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009).

8 Phaidon, Art & Place: Site-specific Art of the Americas (New York: Phaidon Press Inc., 2014), 50.