“The sculptor no longer works the land. But Harvey Fite’s vision, the singular work of his hands, will last as long as there is stone upon stone, sweeping up from bedrock almost to meet the eternity of sky.”

History

In 1938 artist Harvey Fite purchased 12-acres of land in High Woods, Saugerties, New York. Set within the foothills of the Catskills Escarpment with Overlook Mountain, the southernmost peak of the range as a backdrop, the site would become the setting for Opus 40, a monumental abstract environmental sculpture in bluestone. The piece, which Fite worked on from 1939 until his death in 1976, has received critical acclaim. In a 1989 issue of Architectural Digest critic Brendan Gill described Opus 40 as "one of the largest and most beguiling works of art on the entire continent ... a cousin of Stonehenge and the long since vanished Hanging Gardens of Babylon." [2] Even more significantly the piece, a monumental work of environmental art, would predate the land art movement of the 1960s. In June 1980 Art in America gave a description of the work, saying “Opus 40 is a kind of unintended precursor to Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty and to earthworks such as the ones recently proposed as land reclamation projects in King County, Washington. It is a rare example of monumental outdoor sculpture on the east coast … ” [3]

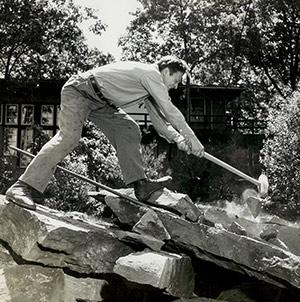

Harvey Fite, photo courtesy of Opus 40

Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Fite spent the majority of his youth in Texas, where his family moved when he was three. According to his memoirs, Fite “entered The Houston Law School, a night school conducted in the Court House by local practitioners for the benefit of aggressive underlings." He dropped out in his third year, returning to the east coast to study the Episcopal ministry at St. Stephen’s college in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. There he discovered a passion for theater, abandoning his studies to join an acting troupe. Fite made a name for himself in the theater, but had yet to discover his true calling in the fine arts. As Fite’s stepson Tad Richards recalls “Backstage one day he picked up a seamstress’s discarded spool and began whittling it. Not long afterward he left the theater, and set about becoming a sculptor.” Fite quickly established a reputation in the field, and that led his alma mater, St. Stephen’s, which had since become Bard College, to hire him to work in its Fine Arts department in 1933.

Shortly after purchasing his property, Fite received funding from the Carnegie Institute to spend several months in Copan, Honduras working with an archaeological team to restore Mayan sculpture. Inspired by the art and stone construction methods he saw on his trip, upon returning to New York he began work on a series of sculptures and an outdoor gallery to hold them. Working alone, and largely self-taught, he built the gallery of rubble from an abandoned bluestone quarry on the property, using an adaptation of dry key stone masonry, a traditional technique which involves the mortarless careful fitting of stone upon stone. The terraced site, which at Fite’s death would span 6.5-acres, would come to be known as Opus 40. Fite conceived of the varied terraces of Opus 40 as pedestals for his sculptural works and he built ramps, walkways, and stairs connecting the spaces to each other. He incorporated the natural landscape, building around trees and pools of water so that they became a part of the piece. He worked without a plan, letting his artist's eye and the shapes of nature combine to form the lines, curves and masses that make up the site. The sprawling piece of environmental art fits intimately into the larger landscape which incorporates a house, and its surrounding woodland.

Photo courtesy of Opus 40

Photo courtesy of Opus 40

Work on the piece was a monumental task. Fite, a lover of history, used antiquated methods of lifting and positioning the stones, often involving traditional tools such as a gin pole and boom, which he later collected into his Quarryman’s Museum. According to Fite’s friend, the novelist Henry Morton Robinson who is best known for his books A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake and The Cardinal, “In his own words he [Fite] wanted ‘to create a sculptural landscape at the foot of Mount Overlook.’ To accomplish this he lifted with his own hands thousands of tons of bluestone rubble—not only lifted the jagged pieces, but carried them distances up to 100 yards to fit them into his scheme. Pieces too big to be lifted were either mounted on homemade wooden rollers or laboriously broken by sledge hammer. It was a titanic operation that a traveling crane might well have quailed at; Fite lost 30 pounds that first summer, but developed, incidentally, the finest pair of shoulders in Ulster County. And in the meantime he had transformed the chaos of rubble into a series of level terraces which were to be the pedestals for individual pieces of sculpture; his own, as well as the work of others.”[4] When in 1962 he installed the 9-ton bluestone monolith at the center of the site using ancient Egyptian methods to maneuver it into place, Fite realized that the site had become too large to hold the series of stone sculptures for which it was originally intended. It only served to overpower them -- Opus 40 had become a work of art in its own right. He gradually began moving his other works of sculpture to other parts of his property.

Fite retired from his work at Bard in 1969, but continued to work on Opus 40 until he passed away during an accidental fall in the quarry in 1976. His widow opened the site to the public in 1977 and in 1978 placed it under the management of the newly created non-profit foundation Opus 40, Inc. In recent years the site has served as a venue for concerts and performances.

Opus 40 is internationally recognized. The site was included in a 1978 exhibition titled Probing the Earth: Contemporary Land Projects at the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden on the National Mall in Washington D.C. The exhibition was curated by John Beardsley and included works by some of the most significant figures in the contemporary Land art movement: Richard Fleischner, Michael Heizer, Nancy Holt, Richard Long, Robert Morris, James Pierce, Charles Ross, Charles Simonds, and Robert Smithson. England's Phaidon Press which bills itself as the “premier publisher of books on the visual arts” included Opus 40 in its 2013 book Art & Place: Site-specific Art of the Americas, as one of the most important American works of site-specific art. According to the publisher, more than 3,000 sites were considered for the publication, out of which only 170 were selected. The site was named a National Historic Landmark in 2000 and a local landmark by the Saugerties Historic Preservation Commission in 2004.

Photo courtesy of Opus 40

Threat

Any piece of environmental art is at the mercy of nature and requires ongoing maintenance. Hurricane Irene in 2011 and Hurricane Sandy in 2012 caused damage to several portions of the site. In the fall of 2012, water buildup exacerbated by both these storms caused a 14-foot high vertical wall in one of the oldest parts of the site to collapse. Since that time expert stonemasons have been enlisted to consult on the damage and restore the site.

In the summer of 2012, master stonewaller Sean Adcock of North Wales, United Kingdom and Tomas Lipps of the Stone Foundation, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, led a team in taking down and rebuilding a portion of Opus 40's 11-foot-high central ramp to demonstrate the feasibility of restoring the collapsed wall. More recently, during the summer of 2014 a team led by stonemason Timothy Smith of Clermont, New York, completed prep work for the restoration, removing and stacking the loose stone. The final phase of the restoration, which will be headed by Adcock, is scheduled for the spring of 2015.

1 Ann Gibbons, “Opus 40’s magnificence set in stone,” The Daily Freeman,August 25, 2013.

2 Brendan Gill, “A Sculptor’s Obsession in Upstate New York,”Architectural Digest, March 1989, 46-54.

3 Sarah McFadden, “Going Places, Part II: The Outside Story,” Art in America, June 1980, 51.

4 Tad Richards, “Harvey Fite and Opus 40, circa 1945,” Tad’s Night with the Language Thieves Blog, March 23, 2014.