Innisfree

Millbrook, NY

For Beck each cup garden was a framed picture, a composition created by the harmony, or tension, or those elements which he chose to impart. He created these pictures not to be looked at but to be looked into. The eye of the intellect must penetrate the picture for the message. — Lester Collins, Innisfree An American Garden

History

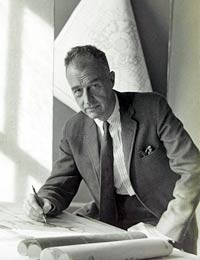

Lester Collins. Photo courtesy Innisfree

Foundation

In the 1920’s Walter and Marion Beck purchased several hundred acres in Millbrook, New York, for their summer residence. They built a Queen Anne Style house on the undulating and largely wooded property which sloped downwards towards a 40-acre glacial lake. Walter an artist and teacher, and Marion, an heiress, had a shared interest in horticulture which led them to begin a garden on the estate grounds. The Becks’ initially surrounded the house with traditional English terraced flower gardens and expansive sweeping lawns. Then, while in London in the 1930s, Walter discovered references to and images of the gardens of the eight-century Chinese poet and painter, Wang Wei. After extensive travel and research, he was prompted to experiment with a series of Asian-inspired gardens on the grounds at Innisfree, using Wei’s concept of distinct garden vignettes. Beck called these small, three-dimensional picture-like landscapes, “cup gardens” referencing their self-contained nature.

In 1938, the Becks met landscape architect, Lester Collins (1914-1993). His first visit to Innisfree was that spring, and the three were soon working together on the Becks’ landscape. At the time of their meeting, Collins, who had already completed his undergraduate degree at Harvard, was pursuing an M.L.A. at the Graduate School of Design. There he was influenced by the European Modernist ideas of Walter Gropius and Christopher Tunnard. Before starting his Master’s coursework, he had traveled through China, India, Japan and Tibet, finding many similarities to Modernist design in these ancient cultures.

Graduating from Harvard in 1942 during World War II, Collins traveled overseas to serve in the British Eighth Army. Returning from service in 1945, he joined the faculty at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and quickly became Dean of his department. In 1954, Collins left Harvard to spend a year in Japan as a Fulbright Scholar, studying traditional garden design and construction methods, and working with a native scholar of Medieval Japanese to translate the 1,000 year-old Sensai Hisho, or Sakuteiki, the seminal Secret Garden Book, into English.

Photo © Matthew Bensen

The Becks found a kindred spirit in Collins whose work on the Innisfree landscape became a lifelong passion. Embracing the Becks’ vision, Collins transformed their inspiration into a unified whole. Over five decades he experimented with, edited and refined his design, using Chinese, Japanese and Modernist principles to create new gardens, and tie Beck’s “cup gardens” into the broader landscape. Together, Walter and Lester selected stones from Innisfree’s rocky woodlands and set them into the landscape, individually, in groups, and as waterfalls, often inspired by the ideas and specific instructions found in the Sakuteiki. Linking such set pieces by carefully choreographing movement and experiential tone, Collins created a distinctly American stroll garden. In describing traditional Chinese gardens, Collins equally described his own work: “A view of the whole is impossible...The observer walks into a series of episodes, like Alice through the looking glass.” Collin’s vision for the site was dynamic; his work used key elements – like his yarimizu (the oxbow in Innisfree’s meadow stream) done in the 1950s; distinctive plantings; and major water features to gently draws visitors around the lake and through the undulating terrain.

Before Walter’s death, the Becks decided to endow a foundation (with Collins serving as its president) for the “study of garden art at Innisfree.” Much like Dumbarton Oaks, with which Collins was involved both while at Harvard and afterward, it was envisioned that scholars and students would live and work onsite, and that conferences, exhibitions, and publications would be produced. Plans changed when Marion died in 1959. Medical expenses from a lengthy illness consumed her financial resources. Instead of using an endowment to preserve the garden and create a study center, the newly formed nonprofit had to borrow money to settle the Becks’ debts to save the site from being sold. In the early 1970s, the Innisfree Foundation sold land surrounding the 185-acre core to Rockefeller University for use as a research station, allowing Innisfree a measure of financial security.

As President of the Innisfree Foundation, Collins shaped the nonprofit that exists today. He used his expertise to usher in the physical transition to accommodate public visitation, doubling the size of the garden and enhancing the breadth of experience it offered. And, as designer and steward, he continued to maintain the spirit that he and the Becks envisioned for Innisfree – a careful and contemplative union of nature and design expressed in rocks, water, sky, lawn and trees.

Patron

Walter and

Marion Beck

Threat

While Innisfree’s short-term legacy is secure, challenges remain in the transition from private estate to public garden. Innisfree Garden has been open to the public since 1960 and the design changes and low-cost, environmentally sensitive maintenance practices developed by Lester Collins have stood the test of time. The funding base, however, is limited primarily to the endowment and admissions, which simply is not enough. The garden is maintained, but some major maintenance projects have been deferred, new initiatives are rare, and the additional expense required to hire professional staff is out of reach. Despite exceptional investment performance and constrained expenditures, the foundation is spending down on its endowment more than they feel is prudent.

How You Can Help

The Innisfree Foundation’s endowment is currently being spent at a rate of approximately 7% each year. People who know and love Innisfree can help spread the word to expand and energize the garden’s community of admirers. People who are new to Innisfree, can visit the garden or explore the Web site and the many books and articles in which it is featured. Supporters can also help by providing financial assistance to secure the garden’s future, address deferred maintenance projects and foster the study and understanding of garden art at Innisfree. To make a donation and/or find out more about Innisfree, you can visit the Innisfree Garden Web site.

Learn More

Innisfree Garden

362 Tyrell Road

Millbrook, NY 12545