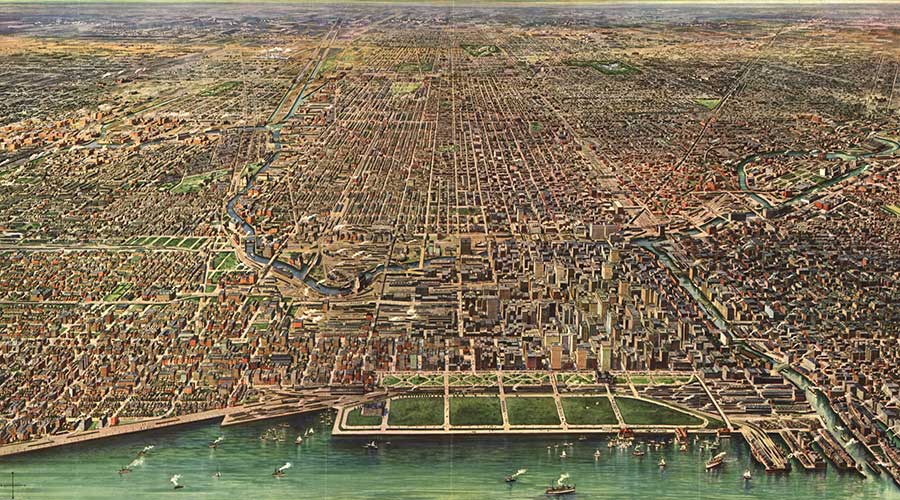

View of Chicago. Image © Arno B. Reincke, 1916.

View of Chicago. Image © Arno B. Reincke, 1916.

“The advantages of improved Nature are obvious. A Saturday in Lincoln Park alone is sufficient to establish its superiority over wild and uncultivated Nature. You have hills which are not too high to climb, sheets of water whereon your boats may float with the security, if not the grace, of a swan; banks to recline on without being haunted by the terror of snakes or black bugs; good roads to drive on that are never dusty or too muddy; rustic bridges to cross without the danger of breaking through… the delusion of bucolic pleasures without the stern reality of bucolic fatigue, monotony, and stupidity.”

Before the Blaze

Derived from the Central Algonquian language of the Miami and Illinois tribes, the word “chicago” referred to wild leeks that grew in the watershed of a river that emptied into Lake Michigan. The river, like most in the region, was a sluggish, meandering watercourse that drained the wet prairie, dry grasslands, and dense forests of the mid-continent. A remnant of glacial retreat, the flat landscape was pocked with lakes, swamps, and bogs. In the wake of the glaciers, rocky, poorly-drained soils and moraines spread across the limestone bedrock that lay close to the surface. The grasslands and oak/hickory forests attracted large mammals such as bison and elk, which in turn attracted humans. Game trails along ridges and sandy beaches became routes navigated by Native Americans, followed by French traders who arrived in the Great Lakes region in the 1670s. From 1682 to 1763, the French laid claim to the region.

In 1795, the American government acquired a parcel of land at the mouth of the Chicago River. By 1808, Fort Dearborn was established on a hill to protect the portage where the river flowed into Lake Michigan. The palisaded fort was burned by Native Americans in 1812 and rebuilt four years later, remaining a military outpost until the 1830s. In 1837, the 54-acre military reservation was decommissioned and a 20-acre section of the land was designated a public park (the precursor to today’s 319-acre Grant Park). In 1836, officials had declared that the lakefront would be maintained as “Public Ground – A Common to Remain Open, Clear, And Free of Any Building, or Other Obstruction Whatever.” A year later, the City of Chicago was incorporated with the motto Urbs in Horto, a Latin phrase that translated to “City in a Garden.”

In the 1830s, the first streets in Chicago were laid out by James Thompson. His grid extended into Chicago Thomas Jefferson’s nationwide Land Ordinance of 1785, which ignored topography, natural landscape features, and cultural precedents in favor of straight lines running in the cardinal directions, forming blocks of one square mile. As the grid expanded with Chicago’s growth, standardized lot sizes and road widths were adopted, leading to spatial homogeneity. Land speculators, attempting to attract people to their development projects, often reserved small parcels in residential areas for use as privately owned, publicly accessible parks. Washington and Vernon Squares (the former no longer exists) were early examples of this practice. In 1847, the Chicago Horticultural Society was established by William Ogden, the city’s first mayor. Hosting exhibitions and disseminating information on botany and gardening, the Society comprised Chicago’s elite doctors, real estate developers, and businessmen. It wasn’t until 1854 that the first municipal park was established, the eleven-acre Union Square Park.

In 1836, work commenced on the construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal, which would eventually stretch 96 miles to connect the Great Lakes with the Mississippi River. Opened in 1848, the 60-foot-wide canal, dug primarily by Irish, German, and Dutch immigrants who then settled in Chicago, traversed the center of the city. Although it accommodated passenger service in its early days (displaced by the Chicago & Rock Island Railroad, completed in 1854), the canal was primarily used for trade. Lumberyards, meatpacking plants, and stockyards were established in Bridgeport, where the canal met the Chicago River. In 1865, the 475-acre Union Stock Yard opened south of Bridgeport.

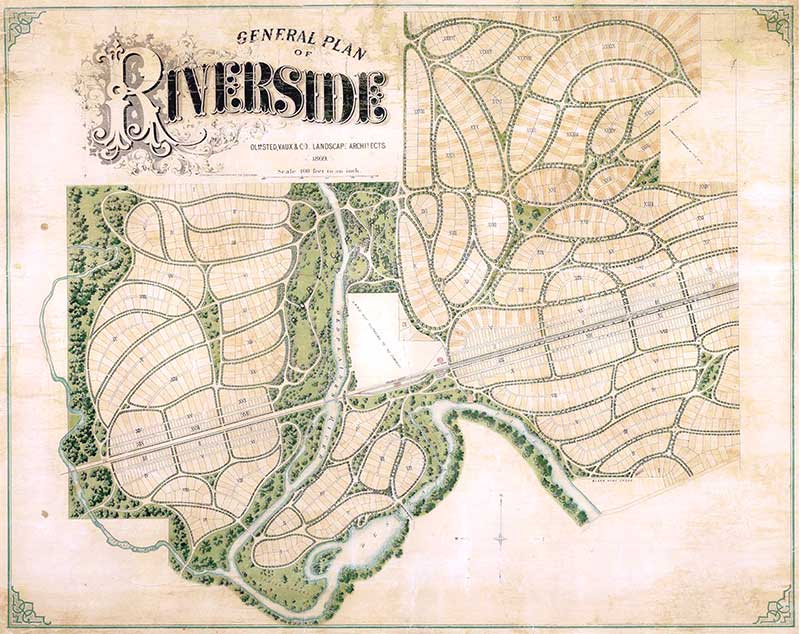

Throughout the second half of the century, railroads linked Chicago to the rest of the country. The city—a frontier metropolis of almost 300,000 residents in the 1870s—established itself as a hub for freight and passenger rail; headquarters for several railroads were established in Chicago and it became a manufacturing center for locomotives and freight cars. So-called “suburban utopias” emerged along the railroads, while heavy industry and agricultural centers took advantage of the freight lines to move raw and processed goods. Horse-drawn streetcars appeared in the 1850s and, within a decade, streetcars simplified commuting, first to the outer neighborhoods and then to the hinterlands. In 1857, the Lake Forest suburb, 28 miles south of Chicago, was designed by Almerin Hotchkiss with a plan that was sensitive to the site’s topography and scenic qualities. By the 1880s, railroad suburbs such as Franklin Park, Kenilworth, and Evanston made it possible for people to work in Chicago but live in the idyllic countryside, escaping noise and pollution. In 1863, the Riverside Improvement Company was founded by the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad ten miles west of downtown. Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., and Calvert Vaux designed the 1,600-acre parcel, which included large lots, hotels, and curvilinear streets that followed the site’s natural topography. Sixteen miles south of the city, railroad magnate George Pullman established his 3,500-acre company town, designed by architect Solon Beman and landscape architect Nathan Barrett in 1879. Riverside was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1970 and Pullman’s development was designated a National Monument in 2015.

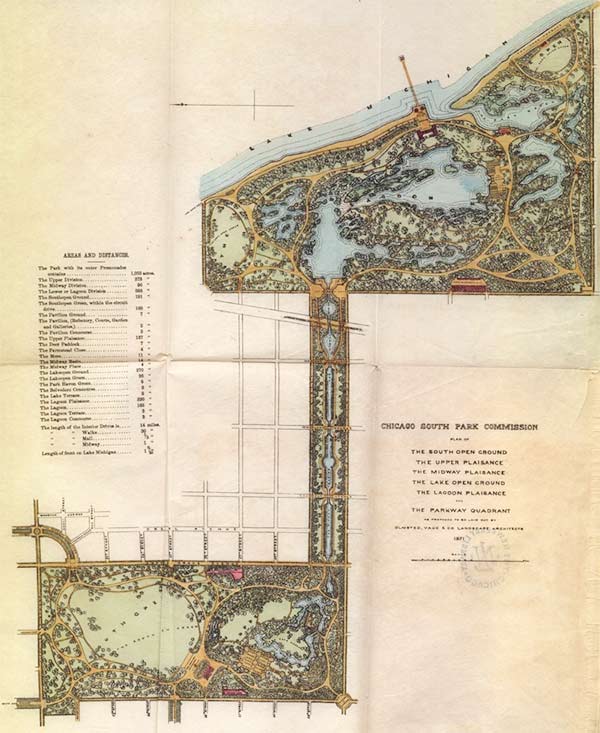

In 1866, the Chicago Times published a plan that promoted a 2,240-acre system of interconnected parks and boulevards. As the plan (reduced to 1,800 acres) was being implemented three years later, voters passed legislation to create the Lincoln, South, and West Park Commissions in the city’s three districts. In 1867, Dr. John Rauch was appointed the superintendent of the Board of Health. Addressing the cholera epidemic, Rauch recommended the removal of City Cemetery, which was laid out in 1836 near the shore of Lake Michigan. Bodies were reinterred at Calvary, Rose Hill, and Graceland cemeteries and the 60-acre lakefront property became Lincoln Park, designed by Swain Nelson and Olof Benson. The designers capitalized on the former cemetery’s inherent qualities to lay out formal and informal areas with lawns, pavilions, lakes, walks, and carriage roads. Zoological gardens, memorials, and a conservatory came later.In the West Park System, architect William Le Baron Jenney developed plans for three parks: Each park—the 200-acre Humboldt, the 180-acre Douglas, and the 185-acre Central (renamed Garfield in 1881)—included a dominant water feature, broad greenswards, masses of informal tree plantings, and curvilinear carriage roads and pedestrian paths. The parks were connected by a system of axial, tree-lined boulevards, which terminated within the parks at fountains and memorials after passing through formal gates. For the South Park System, Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., and Calvert Vaux developed designs for Washington and Jackson Parks, united by the Midway Plaisance. Their plans, which called for a pastoral collection of greenswards, water features, and meandering carriage drives, were destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. That conflagration, originating in a barn on DeKoven Street and blazing for almost two days, destroyed three-and-a-half square miles, leaving a third of Chicago’s population homeless and approximately 300 people dead.

Memories of the Chicago Fire, 1871. Image © Julia Lemos, 1912.

Memories of the Chicago Fire, 1871. Image © Julia Lemos, 1912.

From the Ashes

In the aftermath of the fire, Chicago was quickly rebuilt, expanding its boundaries in all directions. Debris from the fire was dumped into a lagoon near Lake Michigan, providing the land for the construction of the 319-acre Grant Park designed by Edward Bennett. In 1872, H.W.S. Cleveland was hired by the South Parks Commission to develop the earlier plans created by Olmsted and Vaux, although these were scaled back due to financial constraints. Cleveland also made recommendations about Chicago’s boulevards: Hoping to break the rigid homogeneity of the city grid, he suggested that radiating, tree-lined avenues be laid out on the diagonal of the grid, with commercial, cultural, and residential blocks created.

In the 1880s, plans for the commemoration of Christopher Columbus’ discovery of America were underway. Although New York, St. Louis, and Washington, D.C., were under consideration, the U.S. Congress eventually selected Chicago as the location of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Architect Daniel Burnham was selected to manage the creation of the fairgrounds and its buildings. Burnham, who worked with a number of noted architects to design the palatial buildings that would comprise the Exposition’s neoclassical “White City,” collaborated with Olmsted to develop the grounds on Jackson Park and Midway Plaisance. This commission provided Olmsted the opportunity to realize the design he had created with Vaux: Some 27 million people visited, and the Exposition set the precedent for the Beaux-Arts style of landscape design that dominated City Beautiful projects for the next 50 years.

Court of Honor at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Image © Chicago Historical Society.

Court of Honor at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Image © Chicago Historical Society.

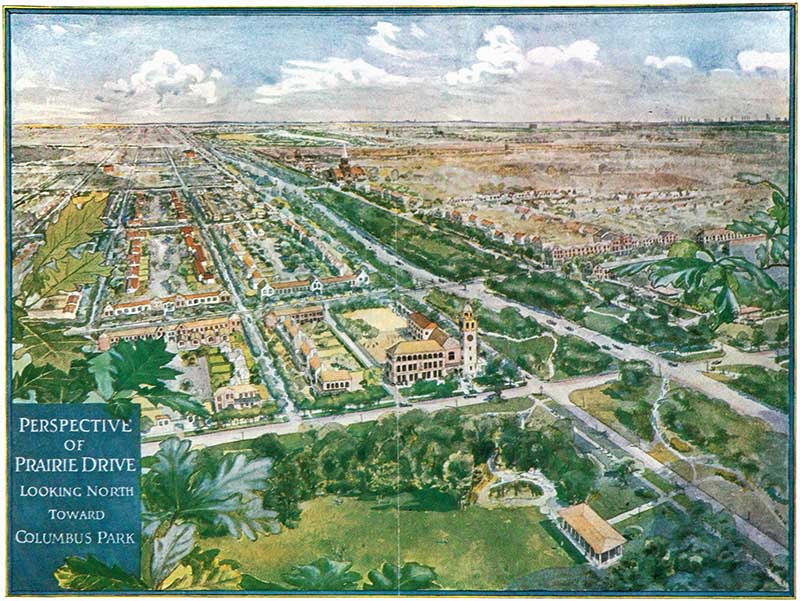

With Chicago’s population exceeding 1.5 million people by the turn of the century, the state legislature authorized the acquisition of more parks in 1899, and in again 1903. Lake Shore Drive, originally laid out by Nelson and Benson in the 1870s, was extended to connect the Lincoln and the South Park systems. Neighborhood parks such as Wicker, Jefferson, and Vernon were enhanced with tracks, pools, field houses, and play equipment—some of which was designed by Olmsted Brothers. In 1909, Burnham and Edward Bennett developed the Plan of Chicago, which proposed a City Beautiful scheme for the city. Goals outlined in the “Burnham Plan” included connecting surrounding suburbs to the downtown with concentric and radial boulevards, consolidating rail networks into a few stations, and developing a 20-mile-long linear shoreline park along Lake Michigan.

This period also marked the evolution of the Prairie Style, a uniquely Midwestern tradition of landscape architecture developed by Jens Jensen, O.C. Simonds, and Alfred Caldwell. The style emphasizes horizontal expanses, outdoor rooms, native plants, and meandering, stream-like water features. Exemplary projects in Chicago include Jensen’s designs for Humboldt and Columbus Parks and the Garfield Park Conservatory; Simonds’ redesign of Graceland Cemetery (earlier developed in the Picturesque style by Swain Nelson and H.W.S. Cleveland); and Caldwell’s designs of the Lily Pool in Lincoln Park and Skyline Park, which surrounds the 70-story Lake Point Tower.

For the next two decades, more than $300 million was spent on the realization of various components of the Burnham Plan until the Great Depression halted its pace in the 1930s. New Deal programs such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA) created opportunities for some of Chicago’s unemployed (some 700,000 people by 1932). Among other projects, the WPA was involved in the completion of Lake Shore Drive, the construction of the Outer Drive Bridge, and the landscaping of new parkland, such as Promontory Point designed by Caldwell at the southern edge of Burnham Park. The Civilian Conservation Corps worked with the National Park Service to restore historic locks along the Illinois and Michigan Canal.

The U.S. entry into World War II created new opportunities for employment in Chicago, as manufacturing industries kept pace with the military’s need for war goods. Thousands of soldiers were stationed at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station in North Chicago and nearby Fort Sheridan. The Douglas Aircraft Company’s plant in the northwest part of Chicago, decommissioned after the war, was transformed into O’Hare Airport by C.F. Murphy Associates (and later by I.M. Pei Associates) to alleviate traffic at Midway Airport.

Art Institute of Chicago, South Garden. Image © Charles A. Birnbaum, 2008.

Art Institute of Chicago, South Garden. Image © Charles A. Birnbaum, 2008.

By the mid-twentieth century, the Chicago Park District managed more than 6,000 acres of land comprising some 169 parks. As the city skyline grew taller and taller, the post-War era witnessed a transition to Modernism, a style embraced by Chicago. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Alfred Caldwell collaborated on the “campus in the park” design for the Illinois Institute of Technology campus in the 1940s. Between 1962 and 1967, landscape architect Dan Kiley developed his intimately scaled South Garden at the Art Institute of Chicago. Kiley also designed a park on the waterfront, later named for Milton Lee Olive, III. During this same timeframe, historic preservation and urban renewal initiatives emerged across the country. Although sometimes at odds with each other, the two philosophies have resulted in a hybridized blend of unique public spaces in Chicago. In 1989, following the discovery of thousands of plans, reports, and correspondence related to the city’s parks, the Chicago Park District established the Office of Research and Planning to guide future development and research.

The development of Chicago’s landscapes has continued apace. In the late 1980s, more than 500 playgrounds were rehabilitated by the Chicago Park District. Between 1989 and 2011, Mayor Richard M. Daley made possible the revitalization of many of Chicago’s historic places, and promoted the development of new parks and open spaces. Parking lots and railroad tracks on the waterfront, owned by the Illinois Central Railroad, were transformed into the 24.5-acre Millennium Park. Other transformative projects include the 20-acre Maggie Daley Park, Pier Park on the historic Navy Pier, and the Bloomingdale Trail and Park, a 2.7-mile-long multi-use amenity on an abandoned elevated railroad. Today, the Chicago Park District manages more than 8,000 acres in almost 600 unique parks. The character of Chicago, at once lifting into the sky and spreading across the landscape, is balanced by the vast expanses of Lake Michigan to one side and the flat prairie on the other.