South Marion Street Parkway (ca. 1909)

South Marion Street Parkway (ca. 1909)

Parks have been important to Denver’s identity since its earliest days. The first – Mestizo Curtis Park (originally known as Curtis Park) – was created a decade after the city’s founding as the mining town of Denver City in 1858. Today, in this most populous city in the Mountain West (and the most populous within a 500-mile radius), mapped parkland represents 8.2% of the city.

The What’s Out There Denver Guide, which spans more than 150 years of design excellence, reveals the most significant public parks and open spaces within this region. Here, in this semi-arid climate rich in natural, scenic, ecological, historic and cultural values, and an unrivaled 200-mile backdrop of snow-capped mountains, the public parks alone total more than 6,100 acres. They range in size from Colorow Point Park at less than one-half an acre to City Park (the city’s most visited park) at 314 acres. And, if all of this is not extraordinary enough, Rocky Mountain National Park, which covers 416 square miles, is just seventy miles away.

City Park (ca. 1901)

This Guide—the first in our series of Web-based, city-focused guides— covers a broad range of landscape types including parks, parkways, boulevards, and park systems, along with cemeteries and burial grounds, botanical gardens, suburbs, golf courses, campus and institutional landscapes, civic centers and plazas, even transit and pedestrian malls. Their styles can be classified as Picturesque or Romantic, Beaux-Arts or Neoclassical, but also include Modernist and Postmodernist examples.

The Denver parks and open space network is an unrivaled local design interpretation that leverages the unique geography of the surrounding Rocky Mountain range and expansive American Prairie grasslands and inherent visual and spatial relationships. This system, with great designs by pioneering landscape architects (e.g. Olmsted Brothers, George Kessler, S.R. DeBoer) working in concert with visionary civic leaders (John Evans, William McLellan, Richard Sopris), provides “comprehensive and coherent linkage between neighborhoods, between public activity centers and the citizens served, between the city and its environment, between business and residents, and, most importantly, between people.” And, none of this was accidental.

Edward Rollandet (ca.1894)

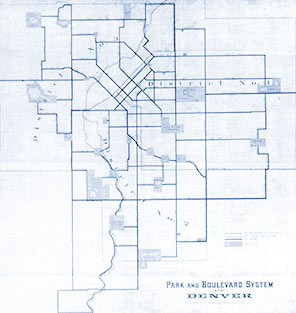

Denver’s park system is unique among other great American cities for having two distinct visions that made this one-time “cow town” a model for city planning and design in the region. First, in 1894, a plan for a “Park and Boulevard System of Denver” established the foundational vision and planning framework that was woven through neighborhoods with destination neighborhood parks (large and small) and cultural destinations (libraries, schools) connected by ribbons of parkways. Here larger parks included a variety of landscape experiences such as lakes that not only served to store water but also reflected the surrounding mountainscapes and established community character. Berkeley Lake Park, Cheesman Park and Washington Park, and parkways such as Speer Boulevard and Williams Street Parkway are popular examples from this era.

This late 19th century plan was expanded by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. in 1912, with his “Mountain Park Preliminary Plan,” which identified more than 40,000 acres that could serve as Denver’s open space. This both stretched the existing system and offered the opportunity for the nation’s premiere landscape architects, Olmsted Brothers, to make a coherent system in the nearby mountains. Where traditional urban planning called for building height restrictions to preserve the views from the city, here the actual sites being viewed – such as the signature canyon walls, mountain peaks and prairie grasslands – were protected by being secured, and turned into parks – examples include Echo Lake Park and Lookout Mountain Park.

As Don and Carolyn Etter, the former co-Managers of Denver's Department of Parks and Recreation, have noted, “In the end, the city became a work of urban landscape art, a garden city if you will. And the subsequent mountain extension of the system was promptly recognized as a unique tourist attraction and a gateway to the Rocky Mountains.”

The city’s in-town and mountain parks continued to be realized until the beginning of the Second World War in 1941 and the opening of Red Rocks Amphitheatre, which served as the capstone on this period of enlightened design and stewardship. Then, as was the case in countless American cities, there was a period of diminished care and management in the 1950s and 1960s. An era of reclaiming cities ensued from the mid 1960s into the 1970s ushering in both bold urban renewal proposals as well as an ambitious historic preservation agenda. This resulted in a new generation of public spaces from parks and plazas to campus and cultural institutions.

Skyline Park. Photo by Charles A. Birnbaum

Beginning in downtown Denver, both Modernist and Postmodernist projects helped reclaim the city with richly designed and unique public spaces including Lawrence Halprin and Sat Nishita’s first block of Skyline Park (1973) and the Sixteenth Street Mall by Hanna/Olin and I.M. Pei Associates (1982). Concurrent with this new type of urban redevelopment, the preservation movement took root in Denver with local landscape architect Jane Silverstein Ries’ involvement in the renewal of Larimer Square (Denver’s first historic district designation in 1971). It came to full fruition in 1986 with the designation to the National Register of Historic Places of Denver’s extensive citywide network of fifteen parks and sixteen parkways (all within the city limits), followed by the Denver Mountain Parks in 1990 (the scope of the designation was expanded in 1995). In 2012, Civic Center joined an even more elite group of sites when it was designated a National Historic Landmark, for its “holistic ensemble of built and landscape elements, significant in the areas of architecture, planning, art and landscape design.”

We hope the What’s Out There Denver Guide is enjoyable and informative as you explore the city’s rich and enviable legacy of parks, parkways and open spaces, which collectively reveal its fascinating evolution. With its unrivaled setting, panoramic views and breadth of design innovation and excellence, the experience of being in these public places should prove uplifting.

Sunrise Amphitheater, Boulder, CO. Photo by Barrett Doherty

Sunrise Amphitheater, Boulder, CO. Photo by Barrett Doherty