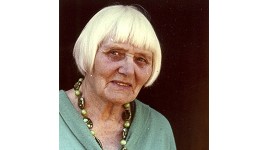

Irma Franzen-Heinrichsdorff Biography

Irma Franzen-Heinrichsdorff (1892 - 1983) was the first woman student of landscape architecture in Germany and, in 1924, the first woman to pass the master's exam in the field of landscape architecture as a state-certified horticultural inspector. Caught up in the events of World War II and making a life in both Europe and the United States, she would overcome significant personal and professional barriers to finally practice in her chosen field.

Born on September 12, 1892, in Witten on the Ruhr, Germany, as the fourth of eight children of Carl and Therese Franzen, Irma Franzen grew up on the outskirts of Witten in a home complemented by a large garden with fruit trees, flowers, and vegetables. Her father, Carl, was a co-owner of the construction company Lünenburger und Franzen, which built in Witten, among other things, the Märkische Museum and, in 1926, the City Hall, which is still a prominent feature of the local cityscape.

After graduating in 1910 from a girls' high school in Witten, Franzen sought to develop her horticultural interests but could hardly count on support from a profession dominated by men. As the author, physician, and psychoanalyst George Walther Groddeck wrote that same year, "The artistic work, horticulture or the art of gardening, is men’s work and will always remain the work of men, like any art, like any great achievement. But the work in the backyard should be taken over by women".

"Gardens depend on women," as Carl Heicke (1862–1938), the editor of the journal Die Gartenkunst put it in 1914, asking rhetorically, "If you need a proof of this, look to England. The basic reason for the unquestionably high state of the art of gardening in England is the lively interest which English women, and in particular the ladies of the better social circles, show in all questions concerning the garden."

Franzen also looked to England, beginning a training course at the Elmwood School of Gardening at Cosham, near Portsmouth, in 1913. However, the start of World War I in 1914 prevented the copmpletion of her training, forcing her to leave England. To her surprise, in 1915-1916 she found a position as the first woman employee on the staff of the nursery Goos und Koenemann in Niederwalluf on the Rhine. Shortly thereafter, in 1917, she registered as the first woman student of garden culture at the Training and Research Institute of Horticulture in Berlin-Dahlem. Her training there included, on the one hand, technical representations and, on the other, the copying of pre-existing garden designs considered to be exemplary. Thus the representation of the design of a garden plot carried out by Franzen in black-and-white is based on a plan published by landscape architect Emil Hardt (1872-?) in 1910 in the professional journal Die Gartenkunst.

After passing an examination in 1919 to become a horticultural technician, Franzen became a member of the German Society for the Art of Gardening (DGGL). She then seems to have worked for landscape architect Wilhelm Röhnick, in Dresden, and for landscape architect Harry Maasz (1880-1946), at the time city gardener in Lübeck and a driving force behind the garden-reform movement of the early twentieth century.

In 1924 Franzen was the first woman at the Training and Research Institute of Horticulture in Berlin-Dahlem to pass the horticultural master examination in the field of landscape architecture as a state-certified horticultural inspector. In March 1925 she married the certified horticultural inspector and landscape architect August Gustav Karl Ludwig Heinrichsdorff (1898-1960?), who was then living in Salzburg. Although the marriage would last but a short time, it allowed Franzen-Heinrichsdorff (as she began to call herself) to shed some reproach for her illegitimate children—a daughter, Waltraud, and a son, Gernot, the latter born just one day after her wedding to Heinrichsdorff.

Franzen-Heinrichsdorff was responsible for a series of exhibits for the Jubilee Horticulture Exhibition in Dresden in 1926. She chose, among other things, to exhibit her plan for the Sauskoyen estate in East Prussia, which caught the attention of architect Hugo Koch (1883-1964), who wrote in the journal Die Gartenkunst: "Irma Franzen-Heinrichsdorf [sic] has contributed beautiful coloured sketches of the generous estate Sauskoyen in East Prussia." In 1928 Franzen-Heinrichsdorff took over the position of landscape architect Johannes Gabriel (1897-1929) in the public garden administration of the city of Dresden. Shortly afterwards she seems to have moved to Lübeck without her husband, working again with landscape architect Harry Maasz until 1930.

Franzen-Heinrichsdorff’s father, who believed that a lady from a good house should not practice in such a profession, eventually intervened to block her independence. He forced her to break off her professional development and bought her a house, known locally as Villa Wobick, in Dangast, a North Sea seaside resort near Varel, Germany. With little means of her own, she had no other option than to move to Dangast. In 1930 her marriage to Gustav Heinrichsdorff, which had always been pro forma, ended in divorce. She did, however, retain her double name (Franzen-Heinrichsdorff) and established a children's home in the relatively spacious house in Dangast that same year.

The political conditions in Germany and Austria, which became gradually more repressive in the 1930s, affected the situation in her children's home. In 1938 and 1939, altogether three children came to Dangast who would have a marked influence on her later life, brothers Peter and Jochen Wurfl from Berlin, and Hans Kaal from Haapsalu in Estonia. Still an unwed woman, Franzen-Heinrichsdorff now cared for two children of her own and three “foreign” children. It seems that the Gestapo (the national socialist secret police) repeatedly searched the children's home, and the local authorities seem to have asked her repeatedly to give up two of the children living with her who were counted as half-Jewish. However, she successfully resisted such demands. Franzen-Heinrichsdorff told the children about designing gardens and showed them drawings to illustrate it.

The three children remained with Franzen-Heinrichsdorff following the liberation from national socialism, finally emigrating to the United States and Canada. In the anarchic years between 1945 and 1948, the ingenuity of the three adopted children contributed essentially to securing the necessary means for survival. Of especial help in this was Hans Kaal (1939-2015), the child who had come to her from Estonia, whose real interests were reading and literature. In Canada and the United States he would become an important translator of German philosophical literature. He also translated the German version of the book about Franzen-Heinrichsdorff.

Franzen-Heinrichsdorff's son Gernot (1925-2016) emigrated to the United States in 1952 with the help of Jochen Wurfl, one of the “foreign" children. He soon realized that in spite of his unusual training, marked more by breaks than by continuity, he understood how to lay out a garden better than most of his fellow workers. Franzen-Heinrichsdorff followed Gernot to Baltimore, Maryland, in the summer of 1953. She did this with the help of Jochen and Peter Wurfl, two of her three “foreign” children who had become American soldiers sent to Europe.

After six months together in Baltimore, son Gernot and mother Irma set out for Colorado Springs. By 1956 the son's work was already so much in demand that he could employ his 64-year-old mother according to her own interests as a landscape architect after an interruption of nearly 30 years. In 1961 Gernot Heinrichsdorff established an independent practice as a landscape architect in Colorado Springs, building what his mother designed.

After a brief hiatus that lasted until 1963, the mother and son designed hundreds of gardens, primarily in Colorado Springs in well-to-do residential enclaves along Wood Avenue and in Broadmoor. They spent many of their leisure hours together gathering alpine plants in the nearby Rocky Mountains, which she cultivated in her greenhouse and he planted in the gardens she designed. Franzen-Heinrichsdorff finally felt that she was in her element and would design gardens for her son until she was over 80 years old.

A collection of her garden designs entitled "Landscape Ideas" served as a prospectus and summarizes approximately 40 garden plans. One striking feature of Franzen-Heinrichsdorff's designs is the clear division of different garden areas. Another unmistakable feature is the preference to use perennials, which are present in nearly every plan. The plans also suggest that the knowledge she gained in the Elmwood School of Gardening remained the foundation of her repertoire as a landscape architect. As much can also be gathered from a few sentences she wrote, already in old age, about her stay there: "The house as well as the garden was laid out very practically and functionally. Besides the house was the tennis court, the perennial beds, the rock garden, beautiful bushes and trees. Next came the useful part of the garden, which contained fruit, berry bushes, vegetables, flowers and a small tree nursery." Further work is needed to determine how much of Franzen-Heinrichsdorff's conceptual beginnings is still present today in the gardens she planned; it seems, in any case, that there is very little left of those gardens.

On March 5, 1983, Irma Franzen-Heinrichsdorff died in Colorado Springs at the age of 90.

Bibliography

Gröning, Gert (2014). Von Dangast nach Colorado Springs. Irma Franzen-Heinrichsdorff 1892-1983. Leben und Werk der ersten Absolventin eines Gartenarchitekturstudiums. Zentrum für Gartenkunst und Landschaftsarchitektur (Hg.), CGL-Studies, volume 22, München.

Gröning, Gert (2016). From Dangast to Colorado Springs. Irma Franzen-Heinrichsdorff 1892-1983. Notes on the Life and Work of the First Woman Graduate in Landscape Architecture. Hans Kaal (translator). Zentrum für Gartenkunst und Landschaftsarchitektur (ed.), CGL-Studies, volume 24, München.