Introduction

Situated at the southwestern tip of Manhattan along the Hudson River, this 92-acre mixed-use community was built on landfill created from New York Harbor dredge and excavation materials from the World Trade Center site. Named after the adjacent Battery Park, the community houses numerous residential, commercial, and retail buildings and nearly 36 acres of carefully integrated parks and open space. A bid to redesign Robert F. Wagner, Jr., Park, located within Battery Park City, seeks to address resiliency issues in the wake of Hurricane Sandy and to "provide better opportunity for food and beverage." This could result in substantial changes to more than Wagner Park: it illustrates a shift in values and priorities for Battery Park City as a whole.

History

The idea for Battery Park City, today a 92-acre mixed-use community located on the southwestern tip of the borough of Manhattan in New York City, began in the 1960s as a reclamation project to replace dilapidated piers along the Hudson River with landfill. In 1968 the Battery Park City Authority (BPCA) was created by the New York State Legislature “for the purpose of financing, developing, constructing, maintaining, and operating a planned community development of the Battery Park City site as a mixed commercial and residential community.”

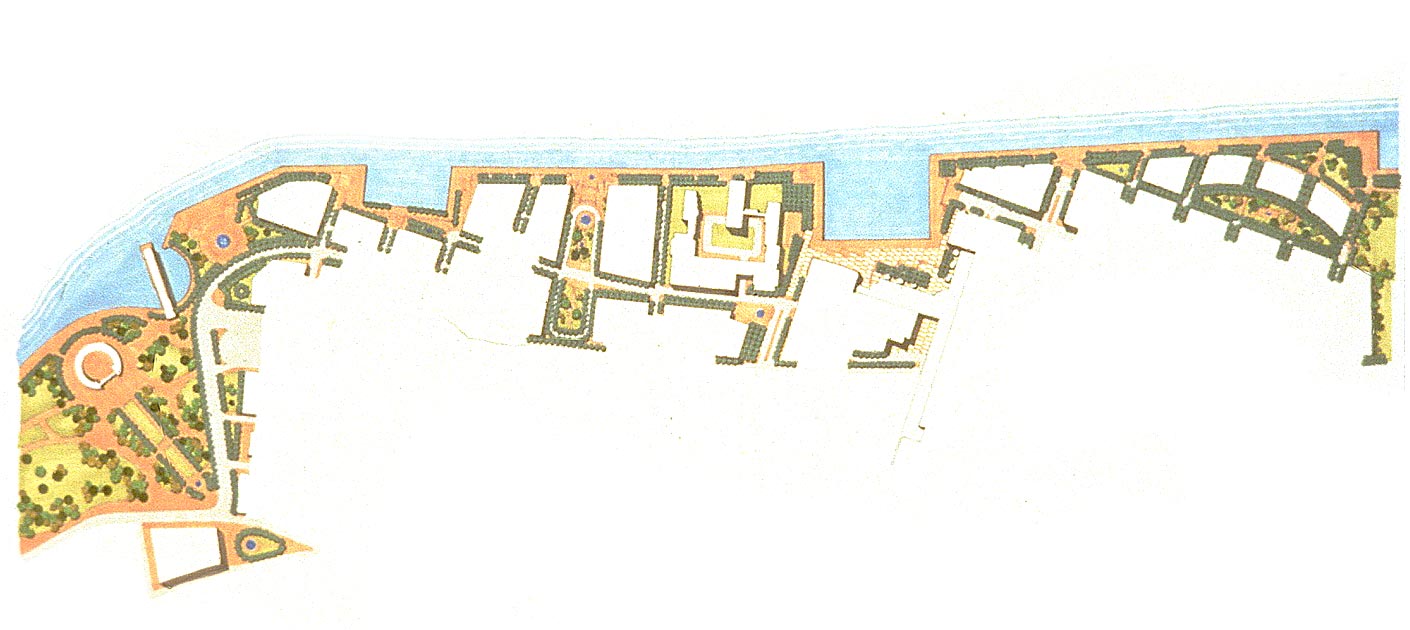

Battery Park City 1979 Master Plan, courtesy of OLIN

Battery Park City 1979 Master Plan, courtesy of OLIN

A master plan was approved in 1969, but there was little progress beyond the creation of landfill in the first decade, especially in the mid-1970s during New York City’s fiscal crisis. The genesis of the current Battery Park City began in 1979 with a new master plan by Stanton Eckstut and Alexander Cooper of Cooper Eckstut. The plan’s 26 parcels were designed independently by different developers, creating a diverse neighborhood fabric that emulated the city’s mixed character. In 1986, New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger praised the project as “far and away the finest urban grouping since Rockefeller Center, and one of the better pieces of urban design of modern times.”

Generous and thoughtfully articulated public spaces were part of the original plan and are integral to the neighborhood’s design and character. Highlights include Rector Park, designed by Innocenti and Webel in 1985; South Cove, a collaboration between artist Mary Miss, landscape architecture firm Child Associates, and Eckstut, opened in 1988; Nelson A. Rockefeller Park, by Carr, Lynch, Hack and Sandell with Oehme van Sweden as landscape architects; and the Esplanade, opened in stages by Hanna/Olin in the 1980s and 1990s. Teardrop Park, designed by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, debuted in 2004. In 1998 architect Cesar Pelli’s World Financial Center was completed, with a Winter Garden by M. Paul Friedberg + Partners. It was restored in 2002 by Balmori Associates. The neighborhood also encompasses significant public art and cultural landmarks, such as the Irish Hunger Memorial. Since 1988, the BPCA has managed and operated these parks and public spaces.

South Cove, Battery Park City, New York, NY, photo by Charles A. Birnbaum, 2010

South Cove, Battery Park City, New York, NY, photo by Charles A. Birnbaum, 2010

Robert F. Wagner, Jr., Park, named for a prominent New York public figure, opened in 1996. It was a collaboration of project lead Laurie Olin with Hanna/Olin, Lynden Miller who designed two gardens based on "hot" and "cool" plant colors, and Machado and Silvetti Associates who performed architectural services. The result was a significant work of Postmodern design. This park is simultaneously a gateway to Battery Park City and an exclamation point at its end. The park also includes sculpture by Louise Bourgeois, Tony Cragg, and Jim Dine.

When it opened in 1996, Paul Goldberger wrote in the New York Times that the park is “one of the finest public spaces New York has seen in at least a generation.” He characterized it as a “lush void” and noted: “The heart of this 3.5-acre public park is a great rectangle of lawn, utterly empty, absolutely flat and tightly enclosed … Somehow it manages to feel as rich and as sensual -- and as tranquil -- as a thousand acres in the country, and it is a minor miracle.”

The park is worthy of an assessment as an historic resource for potential listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Indeed, the larger Battery Park City ensemble – which Paul Goldberger touted in the New York Times as “a national model of civilized urban planning” – should be considered for listing in the National Register. Even though it is less than 50 years old, the usual cut-off point for consideration for listing, exceptions are made, and the ensemble already meets various criteria. Several of the practitioners who worked on parks there, including James van Sweden, Wolfgang Oehme, Diana Balmori, and Richard Webel, are no longer living. The firm Hanna/Olin no longer exists, and various other professionals are no longer practicing.

Landslide Themes

Threat

BPCA wants to replace Wagner Park, one of the 26 parks in the system, with one that better aligns with resiliency measures following the impact of Hurricane Sandy in 2012, which resulted in extensive flooding in lower Manhattan and other sections of the East Coast. If BPCA succeeds, this could open the door to replacing more, or even all, of the parks in the system.

According to the Broadsheet, “The BPCA’s preliminary outline for reconfiguring Wagner Park to withstand flooding during future extreme weather events calls for demolishing the [Machado and Silvetti Associates] pavilion that currently occupies the center of the park (and houses Gigino’s Restaurant and the public rest rooms), replacing it with a larger structure, and erecting on either side a series of columns that will support deployable walls to hold back rising waters.” In addition, the Broadsheet notes: “the restaurant would grow from the current 3,450 square feet to as much as 10,000 square feet.”

At a May 2, 2017, meeting of the Battery Park City Committee of Community Board 1 (CB1), BPCA spokesman Nick Sbordone is quoted as saying: “Hurricane Sandy was a stark warning about the perils of sea level rise and the susceptibility of Lower Manhattan, including Battery Park City, to its effects. In response to a threat we know is increasing, it is imperative to take concrete action now aimed at protecting the community and infrastructure we rely on. The clock is ticking.”

Significantly, while water did reach the lawns, the buildings at Wagner Park did not flood during Hurricane Sandy, because the park was built to withstand a 100-year flood – it did the job it was designed to do. In a recent email, Laure Olin wrote: "When we did the actual design and construction for even the first phase of BPC following our 1979 master plan with Alexander Cooper we raised the entire site above what we understood the 100-year storm to be plus we added a surcharge (additional height) for storms and high tides."

Robert Wagner Park, Battery Park City, New York, NY, photo by Nancy Slade, 2012

Robert Wagner Park, Battery Park City, New York, NY, photo by Nancy Slade, 2012

By contrast, adjacent sites were flooded and critics of the proposed redesign, such as landscape architect Laura Starr, suggest that low-lying areas should be BPCA’s higher priority. In a conversation with Starr on May 29, 2017, she stated: “Topography is a fact – [Pier A] Plaza sits at a much lower elevation and should be addressed first. The solution of addressing that, which is a complicated situation, will likely generate a solution for the adjacent areas. The [proposed] integrated flood protection solution may not necessarily have to involve the most beloved areas of Wagner Park.”

The proposals for Wagner Park are couched in terms of sustainability and resilience, but there may be other considerations. According to the Broadsheet, the owner of Gigino’s restaurant “pays $85,000 per year for the 3,450 square feet. This comes to an annual cost of $24.63 per square foot. According to the Cushman & Wakefield Marketbeat Manhattan report, the current asking rent for retail space in Lower Manhattan is $403 per square foot.”

In fact, among the top five "Objectives" listed on page two of the BPCA's plan for Wagner Park is: "Provide better opportunity for food and beverage.” This is reinforced on page five in the section labeled "Existing Building Issues: Not achieving food & beverage potential."

In the same email from Laurie Olin, cited above, he wrote: "Wagner Park in the form it is in at this moment is a highly successful social space contributing greatly to the life of thousands in the city; to destroy it on the premise that it will solve the impact of climate change on lower Manhattan when all the streets and every building for a mile or more around it remain lower than it is dishonest."

In the opening of his 1986 review of Battery Park City, Paul Goldberger, in the New York Times, observed of architecture at that time that there was “an indifference toward the idea of urbanism, a feeling that individual parts matter a great deal more than wholes.” Projects were treated as “prima donnas, not ensembles.” He continued, “Against this backdrop, Battery Park City, the immense complex moving steadily toward completion on a 92-acre landfill site along the Hudson River in lower Manhattan, is close to a miracle. For here there is a sense of place, and it is a powerful and generally convincing one.”

Battery Park City is a comprehensive work of community planning and landscape architecture, a rare East Coast foray into Postmodernist design that is deserving of greater scholarly attention and evaluation for its careful integration of architecture, landscape architecture, horticulture, and public art.

What You Can Do to Help

Please contact the following elected officials and members of the Battery Park City Authority to urge them to:

- Reject the proposal to drastically alter Robert F. Wagner, Jr., Park, as it would have an adverse effect on this nationally significant work of landscape architecture;

- Support a strong measure to help guide future change; encourage the New York State and the Battery Park City Authority to pursue a Determination of Eligibility (DOE) for listing the Battery Park City landscape ensemble (for the period spanning 1979 – 1996) in the National Register of Historic Places.

Governor Andrew Cuomo

New York State Capitol Building

Albany, NY 12224

(518) 474-8390

State Senator Daniel Squadron

MANHATTAN OFFICE

250 Broadway, Suite #2011

New York, NY 10007

(212) 298-5565

U.S. Congressman Jerrold Nadler

MANHATTAN OFFICE

201 Varick Street, Suite #669

New York, NY 10014

(212) 367-7350

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio

City Hall

New York, NY 10007

(212) 639-9675

Comptroller Scott Stringer

One Centre Street

New York, NY 10007

(212) 669-3916

City Council Member Margaret Chin, District 1

165 Park Row, Suite 11

New York, NY 10038

(212) 587-3159

Dennis Mehiel

Chairman & Chief Executive Officer of the BPCA

(212) 417-2000