Introduction

Overlooking downtown Providence from a terraced plateau, the historic Rhode Island State House and its park-like grounds occupy an elevated site on Smith Hill. The monumental Beaux-Arts structure was designed by the famed architecture firm McKim, Mead & White, with construction completed in 1904. A proposal is currently under way to build an “intermodal transportation center,” potentially to include mixed-use commercial buildings, on the historic lawn of the State House and possibly on the acreage of State House Park, adjacent to the lawn. Although special regulations governing the public land around the State House, including the park, unequivocally forbid any building on open ground, the State of Rhode Island is currently reviewing a response to a “request for qualifications” that would bring the proposed transportation center one step closer to being built.

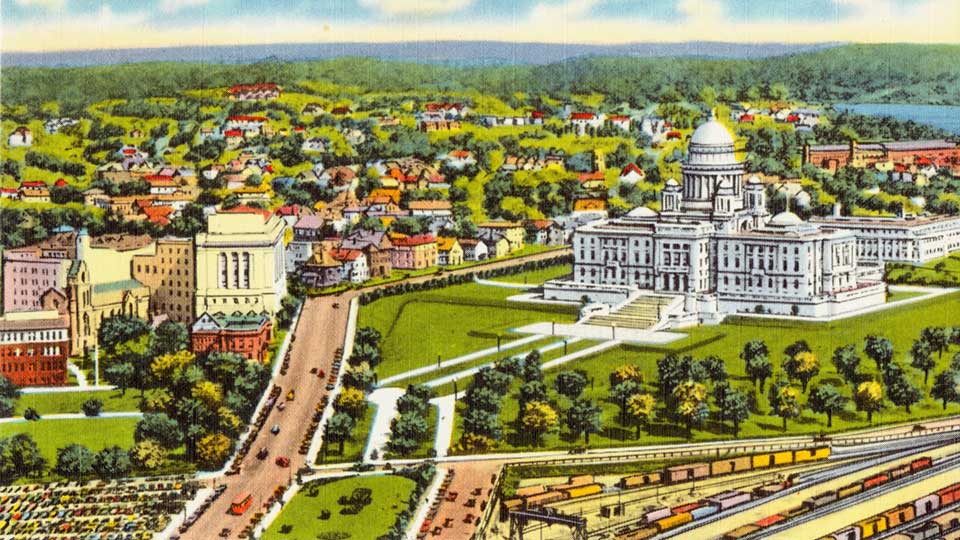

Bird's-eye View from Industrial Trust Building, Providence, R.I.

Bird's-eye View from Industrial Trust Building, Providence, R.I.

History

In 1894, the area of Smith Hill, in Providence, was officially chosen as the site of the Rhode Island State House. The choice had been heavily endorsed by the Public Park Association of Providence, chiefly because any building there “could be readily seen from all parts of the city,” as an 1882 pamphlet produced by the Association proclaimed. Land in the area was also relatively cheap because Smith Hill was then separated from the downtown area by railroad tracks and railyards. The initial six acres of what would become a sixteen-acre site were acquired in 1895. Having won a competition to design the State House, McKim, Mead & White, one of the nation’s leading firms, was awarded the contract, and building began later that same year.

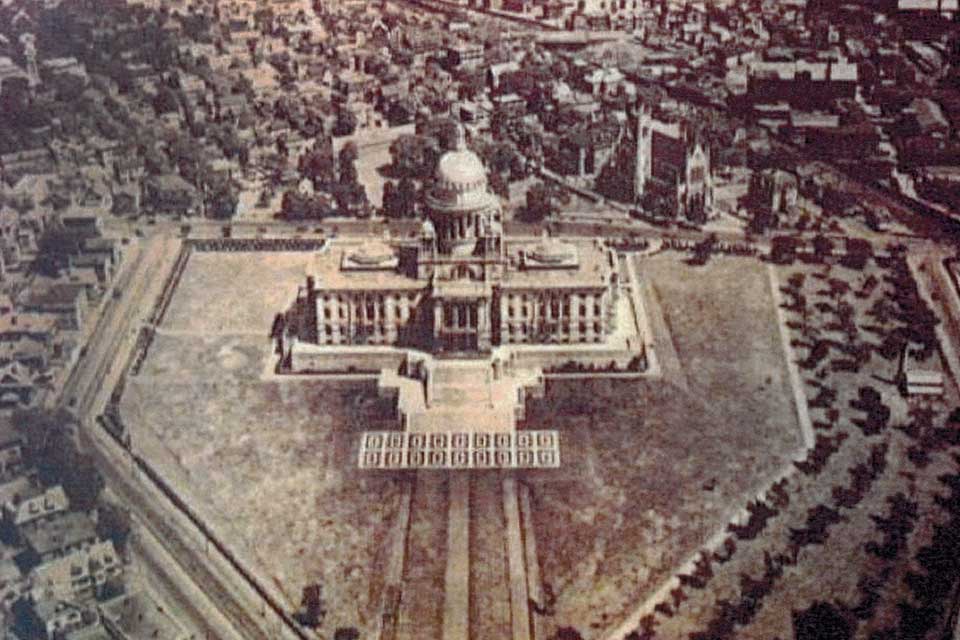

Aerial photograph of the State House grounds, looking north, circa 1920, courtesy of Providence Public Library

Aerial photograph of the State House grounds, looking north, circa 1920, courtesy of Providence Public LibraryA report by the Historic American Buildings Survey states that “a plan by Manning Brothers of Boston was accepted and implemented in time for the delivery of the [State House], its terrace approaches and grounds completed, to the state on June 11, 1904.” The extent of the work completed by the Manning Brothers firm, run by well-known landscape architect Warren H. Manning and his brother, Woodward, is, however, uncertain. In photographs from circa 1907 and 1910, there are trees dotting the otherwise open lawn, and a low, evergreen hedge running the perimeter of the grounds. In 1913, landscape architect John R. Brinley, of the firm Brinley & Holbrook, submitted a “General Planting Plan” for the grounds of the State House, but the extent to which it was implemented is also unknown. Aerial photography circa 1920 shows evenly spaced rows of trees planted along the eastern slope of the lawn, between the footpath that echoed the line of Francis Street, to the west, and Gaspee Street, which formed the eastern boundary of the grounds. By the early 1960s, trees had been planted in allées framing three walkways leading from the southern façade of the State House to Francis Street.

The most radical changes to the landscape came in the 1980s, when a train station, replacing one located farther south, was built on the southeastern border of the State House lawn. The railroad tracks were shifted, Gaspee Street was realigned, and the southern stretch of Francis Street was straightened to create an axial approach to the State House’s southern facade. Three-quarters of an acre were ceded from the State House lawn in the process. To mitigate the loss of acreage, State House Park, just west of the new train station, was created to “serve as an extension of the lawn and positively enhance the esthetic vista from the State House.” In 1981, the Capital Center Special Development District was established, in part, to “create visual and physical linkages between downtown Providence and Smith Hill.” Notably, the new train station, built in 1986, was kept to a single story in height so that it would not compete visually with McKim, Meade & White’s masterpiece, which was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1970.

Landslide Themes

Threat

On June 23, 2017, the Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT) issued a “request for qualifications” (RFQ) for a proposed Providence Intermodal Transportation Center, a public-private partnership to include a transit hub and commercial buildings near the Providence Amtrak station. The plan would see a new multistory transit hub and other buildings constructed on the eastern swath of the State House lawn and, possibly, also on the northwestern corner of State House Park. In order to build the complex on the historic lawn, Gaspee Street would be moved closer to the Capitol, approximately to the position of the current footpath there. Although voters approved a $35 million bond issue for a transit hub in 2014, the location of the project was not specified at the time. The development may also include apartments, hotel space, offices, or a parking garage. It will certainly include a bus terminal (a RIDOT requirement) with up to twenty berths, a “fully integrated retail corridor,” and a direct connection to the train station.

Map showing the effects of the proposed transit hub and commercial buildings, with the potential construction zones in red

Map showing the effects of the proposed transit hub and commercial buildings, with the potential construction zones in red As the RFQ indicates, the plan is subject to approval by the Capital Center Commission. But approving it would require a change in the Commission’s regulations, and, in turn, the endorsement of the State Historic Preservation Commission (and possibility multiple federal transportation agencies). The Commission’s regulations govern the design of every parcel in the Capital Center District, including the historic lawn and the 3.6-acre State House Park, which are being eyed for development. According to the regulations, “The State House Lawn provides a grand and appropriate and magnificent setting for the architecturally significant State House building. The significance of this area should be preserved and maintained” (Design and Development Regulations, as adopted by the Capital Center Commission on February 13, 2003; section 3.4.H, emphasis added). And regarding State House Park, “It is an important link in the open space chain, which extends from the State House Lawn to Waterplace Park and Kennedy Plaza. State House Park shall be a public open space and shall not be used as a development site or to accommodate any off-street parking” (section 5.D.2, emphasis added). The regulations also define and protect the district’s primary view corridors, which “provide strong visual linkages among important public monuments” (section 5.B.5), some of which would clearly be adversely affected by the project currently being proposed. All of this is not to mention that in the early nineteenth century, the predominantly African American, working-class neighborhood of Snowtown spilled onto the eastern slope of Smith Hill. It is difficult to imagine that the area is not archaeologically sensitive, as any attempt to build there would surely soon discover.

Deming Sherman, the chairman of the Capital Center Commission, has already publicly stated his “severe reservations” about the project. Former Capital Center Commission Chairman Leslie Gardner has called the proposal “a little bizarre.” But so far, the only consolation offered for the potential confiscation of the eastern lawn of the 113-year-old State House is that it would, in the words of a RIDOT representative, make the area “symmetrical.”

What You Can Do to Help

On June 22, 2017, Representative Joseph Solomon introduced a bill in the Rhode Island House of Representatives that would prohibit construction “on land that is contiguous to and outside the Rhode Island State House” without first gaining approval from the General Assembly. The bill passed the House unanimously but was not put to a vote in the Senate. Absent such legislation, plans for the development continue to move forward. Members of the public can, however, tell Rhode Island Governor Gina Raimondo to abandon any plans to build on the grounds of the historic Rhode Island State House.

E-mail Governor Gina Raimondo, or write to:

The Honorable Gina Raimondo, Governor of Rhode Island

Office of the Governor, 82 Smith Street, Providence, RI 02903

(401) 222-2080