Themes

Monetization of Open Space

Parks that were originally designed primarily for respite and passive enjoyment are coming under pressure to generate revenue, whether through private commercial development in urban settings or resource extraction, such as mining, in national monuments and wilderness areas. Urban parks, which Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., called “green lungs,” were initially conceived as democratic spaces that were free and open to all. They were also part of the social compact between the public and the municipalities or other governmental organizations that built and maintained the parks. Over the past several decades, municipal budgets have become increasingly strained, and funds for park maintenance, along with other budgetary line-items deemed of lesser importance, have been slashed. More recently, with the renaissance of many of the nation’s leading cities, acquiring parkland has become more difficult as land values surge.

In response to the prevailing conditions, municipalities and some park stewards are carving out sections of public parks to create revenue-generating facilities. For example, some 40% of Nashville’s Fort Negley Park is being considered for a mixed-use commercial and residential complex. Robert F. Wagner, Jr., Park, in New York City’s Battery Park City, is facing a significant redesign that includes a large new restaurant facility in place of open space and the park’s signature architectural feature. Likewise, the managers of New Orleans’ Audubon Park and City Park have converted green space to golf courses, playing fields, dining facilities, and other revenue-generating initiatives. And as the price of land skyrockets in Seattle, the city’s Discovery Park, a scenic reserve meant for tranquility and respite, is being eyed for an arts campus. A swath of the historic lawn of the Rhode Island State House may be forfeited for a transit hub with a mixed-use development. As for national monuments, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke has proposed relaxing management rules for six monuments, two of which are marine sanctuaries. The move would open these rare and cherished places to logging, mining, and other forms of resource extraction.

Audubon Park, New Orleans, LA, photo by Kyle Jacobson and Peter Sommerlin, 2011

Audubon Park, New Orleans, LA, photo by Kyle Jacobson and Peter Sommerlin, 2011

Resource Extraction

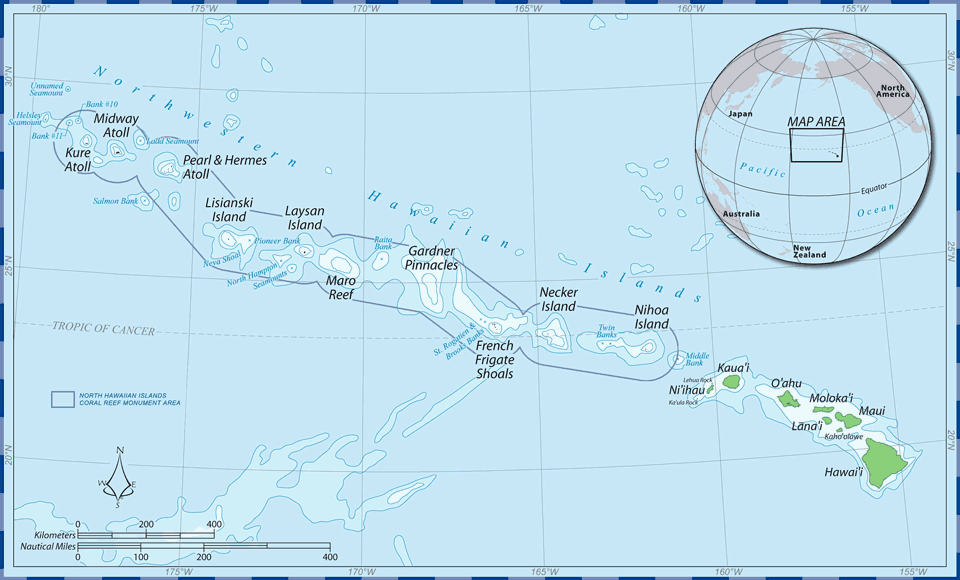

Federally designated national monuments and wilderness areas are losing their protection and will be subject to resource extraction. For more than a half-century, the U.S. public and lawmakers at the federal, state, and local levels have debated the value and safety of oil-and-gas drilling, logging, mining, and other forms of resource extraction. Recognizing that such activity can have a deleterious effect on fragile ecosystems and species, policies have been implemented to set aside land to be maintained and managed as National Monuments and wilderness areas. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke has, however, proposed relaxing management rules for six monuments, two of which are marine sanctuaries. The move opens these sites to logging, mining, and other forms of resource extraction. Meanwhile, in Minnesota, mining has been proposed at the southwestern edge of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, managed by the U.S. Forest Service since 1909 and America’s most visited wilderness area.

Map of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, map courtesy of NOAA

Map of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, map courtesy of NOAA

Detrimental Effects of Shadow

The loosening of building-height restrictions is literally casting shadows over parks and open spaces, diminishing available light for both plants and human enjoyment. In 1881 Calvert Vaux, Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr.’s, Central Park protégé, wrote the essay “Sky and Skyline,” extolling the benefits and importance of a visible skyline for public enjoyment. Today, 136 years later, we can no longer take this benefit for granted, as zoning regulations are being relaxed or nullified to allow new building construction that casts shadows over parks for longer periods of time, diminishing those elements that contribute to the quality and character of our most cherished public parks and open spaces.

In New York City, zoning changes in mid-town Manhattan are all but certain to affect Greenacre Park, a small oasis where visitors can relax and enjoy respite. The park is a finely calibrated work of art reliant on sunlight and dappled light for its sense of serenity and spatial definition. The increased amount of shadow would not only impact the plant materials, it would fundamentally alter the park’s sense of place. In Boston, a precedent-setting “one-time-only” exemption has been granted from the city’s “shadow law” that restricts building heights and the amount of shadow cast over the city’s iconic Boston Common and Public Garden. This would allow for the construction of a large residential-office tower (nearly twice the height permitted by the “shadow law”) that would cast long shadows over the Boston Common for a longer time than allowed under current law. The new construction is on city-owned land, the sale of which netted the city $153 million. The mayor was a strong proponent of the exemption.

Greenacre Park, New York, NY, photo courtesy of Greenacre Foundation

Greenacre Park, New York, NY, photo courtesy of Greenacre Foundation

Park Equity

Freedom of movement and equal public access to parkland are being threatened by the sale and/or privatization of parkland held in public trust—an issue closely tied to the monetization of public open space. By design, public parks and open spaces were amenities free and open to all, regardless of socio-economic status. Because of budgetary and other considerations, parkland held in public trust is today being confiscated, sold, or otherwise privatized throughout the country. In Chicago, for example, more than twenty acres of Jackson Park, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., and Calvert Vaux, has been confiscated for use by the Obama Presidential Center, a privately owned and operated facility. And at parks in New Orleans, playing fields and cultural venues with high entry fees are replacing freely accessible parkland. Similar scenarios are playing out at sites in Milwaukee, New York City, Nashville, Seattle, and elsewhere.

Jackson Park, Chicago, IL, photo by Steven Vance, 2017

Jackson Park, Chicago, IL, photo by Steven Vance, 2017

Devaluation of Cultural Lifeways

Landscapes are often palimpsests that contain the remnants of many different cultures, often spanning multiple generations. The legacy of these cultural lifeways is being lost through the incompatible development of open space. For example, sprawl is threatening the ancestral lands of native peoples in northern California’s Coyote Valley, while Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, once the site of Native American settlements and a Paleo-Indian culture, faces threats from resource extraction.

Sites and features from the Colonial era are also threatened, such as the James River, where proposed transmission towers would negatively impact historic Jamestown, Colonial National Historical Park, the Colonial Parkway, and the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. Sites significant for their associations with the Civil War and African American history are also in danger, such as Fort Negley Park in Nashville, being eyed for a mixed-use development.

Transmission towers running along the James River, photo by Barrett Doherty, 2017

Transmission towers running along the James River, photo by Barrett Doherty, 2017