This 2.1-acre park, adjacent to the midpoint of the twelve-acre Martin Luther King Jr. Promenade (originally named Marina Linear Park) in San Diego, was created as the collaborative design effort of landscape architects Martha Schwartz and Peter Walker beginning in 1987. Though often credited to Walker as the park was completed a decade later under the auspices of his then-firm Peter Walker William Johnson and Partners, Walker and Schwartz were equal partners in the original vision for the park, which was inspired by the many parallel lines of a serape cloth. Due to the changeable surrounding cityscape of hotels, museums, and the San Diego Convention Center, the central landscape of the linear park, Children’s Park and Pond, faces continual threat of redevelopment or erasure.

History

In 1983 landscape architects Peter Walker and Martha Schwartz combined their individual firms to create The Office of Peter Walker and Martha Schwartz in Boston. The couple had married in 1979, after meeting while Schwartz was studying at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD). Their subsequent professional partnership was born out of a mutual appreciation of landscape as an art form. While Walker had been practicing as a landscape architect since the late 1950s, Schwartz entered the field through an interest in land art, having earned a bachelor of fine art from the University of Michigan in 1973 before obtaining degrees in landscape architecture at the GSD and University of Michigan in 1977.

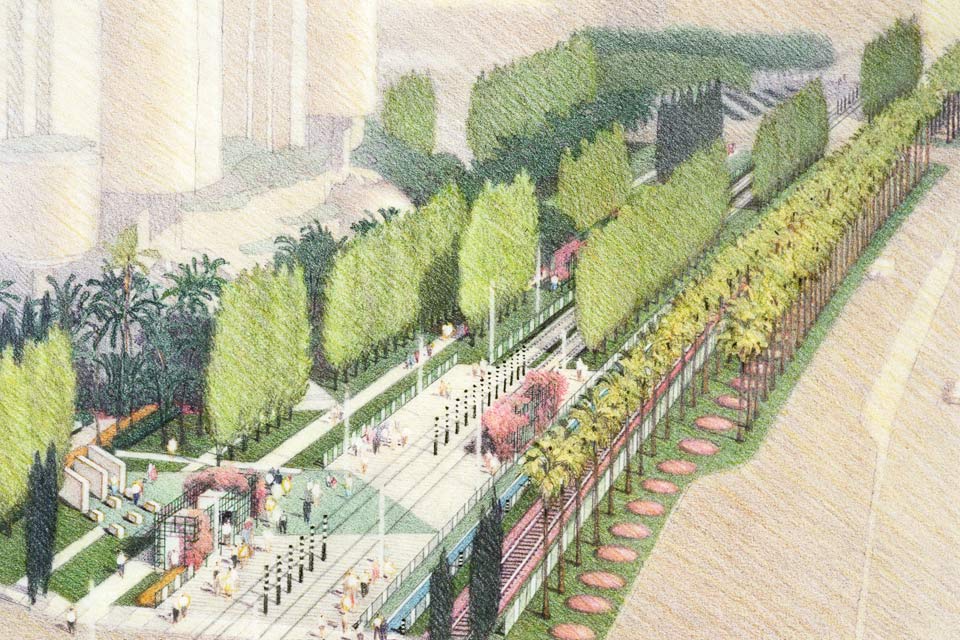

Aerial view of Children’s Park and Pond, San Diego, CA; photo courtesy Martha Schwartz Partners, 1988.

Aerial view of Children’s Park and Pond, San Diego, CA; photo courtesy Martha Schwartz Partners, 1988.

By 1984 the firm had relocated to San Francisco. Drawing upon their respective backgrounds, the partnership sought to create designs that challenged traditional notions of landscape architecture interpreted through the lens of contemporary art. Throughout the duration of their joint practice, which was active through 1990, Walker and Schwartz continued to each take the lead on specific projects for the firm, based on their individual design interests. The one truly collaborative endeavor was their design for Marina Linear Park, later renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Promenade, in San Diego, California.

In 1987 The Office of Peter Walker and Martha Schwartz won a competition to design this twelve-acre linear landscape along Harbor Drive. The space for the park was designated as one element of a downtown redevelopment for San Diego; the majority of the segments alongside it became governmental agency buildings or were allocated to developers for retail or housing. The area that would become the park could not be set aside for building construction, as it primarily consisted of train tracks. Only one parcel along this route was left as open space; this would become Children’s Park and Pond.

On one side of the tracks lay the North San Diego Bay waterfront in a straight line, while the other side comprised a series of triangular parcels that conformed to the grid of the city coming in on a diagonal. Inspired by this irregular geometry and by the framework of the train tracks, Walker and Schwartz created a series of lines in the landscape with bands of grass, trees, flower beds, asphalt, gravel paths, and the train tracks, collectively evoking the pattern of a serape. The open lot toward the center of the linear park was divided into two sections. A geometrically planted pine grove extended north from a 200-foot-diameter, circular pool, bisected by the promenade and the Santa Fe Railroad. A shaded grove of Canary Island pines contained a prominent array of grass mounds.

The park was constructed over the course of ten years, during which time the surrounding urban fabric continued to change. Between the winning of the competition and the start of construction, a children’s museum was built on one of the parcels on the city side of the tracks. The project started to become known as “Children’s Park,” though Schwartz and Walker had not intended it to be a space specifically for children. This led to many changes to their design during construction and in the years that followed, most notably the removal of the mounds, due to alleged safety concerns. The mounds were replaced with flat, circular grass beds that were later filled with gravel, resulting in a uniform ground plane. The concrete rings that once encircled the mounds were retained, but by flattening the mounds, the design intent had been altered. The pool was also never intended as a splash pool for children, but rather created as a formal element connecting the conference hotels with what was anticipated to be another hotel on the other side (before it became a children’s museum).

Curving walkways with grass mounds and Canary Pines at Children’s Park and Pond, San Diego, CA; photo courtesy Martha Schwartz Partners, 1988.

Curving walkways with grass mounds and Canary Pines at Children’s Park and Pond, San Diego, CA; photo courtesy Martha Schwartz Partners, 1988.

In 1992 Schwartz returned to Cambridge to become a tenured professor in Practice of Landscape Architecture at the GSD, where she has focused her work and teaching on the role of landscape architecture in the face of climate change. With her solo firm, she has worked on projects around the globe, and was awarded the 2020 ASLA Design Medal and the Women in Design Award for Excellence from the Boston Society of Architects, among many other accolades. Children’s Park and Pond, which opened in July 1995 in anticipation of the 1996 Republican National Convention in San Diego, was implemented by Walker’s successor firm, Peter Walker William Johnson and Partners, after Schwartz’s move to the east coast; however, her original vision for the serape lines remained integral to its design.

Threat

Children’s Park and Pond has been under threat since its inception, considering that the function of the park never matched that of the landscape architects’ intent. Though the original mounds were removed within the first two decades, their footprints remain and there is an opportunity for the park to be reimagined to incorporate some of the original design intent.

Beyond the erasure of the intended design, this park also faces continual threat of destruction in its entirety, due to its prime downtown location and proximity to many large-scale development projects. In 2011, Civic San Diego approved a 3.2 million dollar master plan for the park, including new landscaping, re-grading of the pond, and the proposed addition of playground equipment; however, the project lost state funding in 2012 and was never implemented. Since then, various redevelopment ideas have been put forth, including a proposal for an off-leash dog park.

As reported in the San Diego Union-Tribune and the San Diego Downtown News in late 2019 and early 2020, respectively, the City of San Diego has plans for an eight-million-dollar renovation of the park, which would effectively demolish the Schwartz and Walker design. Project construction was originally slated to begin in early summer 2020, with a completion date of summer 2021, though it is unclear whether the novel coronavirus pandemic has moved the needle on that timeline.

Management of the park has changed hands several times throughout the course of its life. Initially under the jurisdiction of the Centre City Development Corporation, Civic San Diego, a city-owned non-profit, overtook operations in 2012. As of June 2019, downtown land use decisions were returned to the city of San Diego by a City Council vote, and Civic San Diego is operating as a separate public benefit company. Thus, it is now up to the city to determine the fate of this landscape.

What You Can Do to Help

Appeal to the San Diego Commission for Arts and Culture and the Save Our Heritage Organization to urge them to preserve the existing park as a significant work of art, as Schwartz and Walker both consider it to be--per San Diego Municipal Code, “public art” is defined as a work that is “specified or designed by” an artist and can include sculpture, earthworks, and other such physical installations in the landscape.

Encourage consideration for listing in the National Register of Historic Places by contacting the California State Historic Preservation Office. Though a work of architecture or landscape architecture typically needs to be at least 50 years old in order for it to be designated a historic resource (the “50-year rule,” as it is commonly known, is a standard that must be met in order for a site to be eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places), exceptions can be made when an individual’s or firm’s body of work can be bracketed, i.e., when the firm no longer exists or when the designers involved have formally retired.

In the case of Children’s Park and Pond, though both landscape architects are still practicing individually, The Office of Peter Walker and Martha Schwartz was dissolved in 1989, and Walker and Schwartz consider the park to be the firm’s only truly collaborative work. Though it may be too late to salvage such individual components as the mounds, the overarching artistic vision of the linear relationship between the train tracks and bands of plantings and paving can and should be saved and integrated into any new design or programming. Since the original designers are still living, there is a unique opportunity to engage them in this process.