Introduction

One hundred years ago, after decades of demonstrations and activism, women won the right to vote.

This year’s Landslide, The Cultural Landscape Foundation’s (TCLF) annual thematic report about threatened and at-risk landscapes and landscape features, uses that milestone as a spark to both look back at the past century of women in landscape architecture, and to assess the role of women in the profession today. The threats to the Landslide 2020: Women Take the Lead landscapes range from insufficient funding and deferred maintenance to outright demolition. The title is derived from a May 13, 1938 New York Times article about women landscape architects that includes the subheadline “Women Take Lead in Landscape Art.”

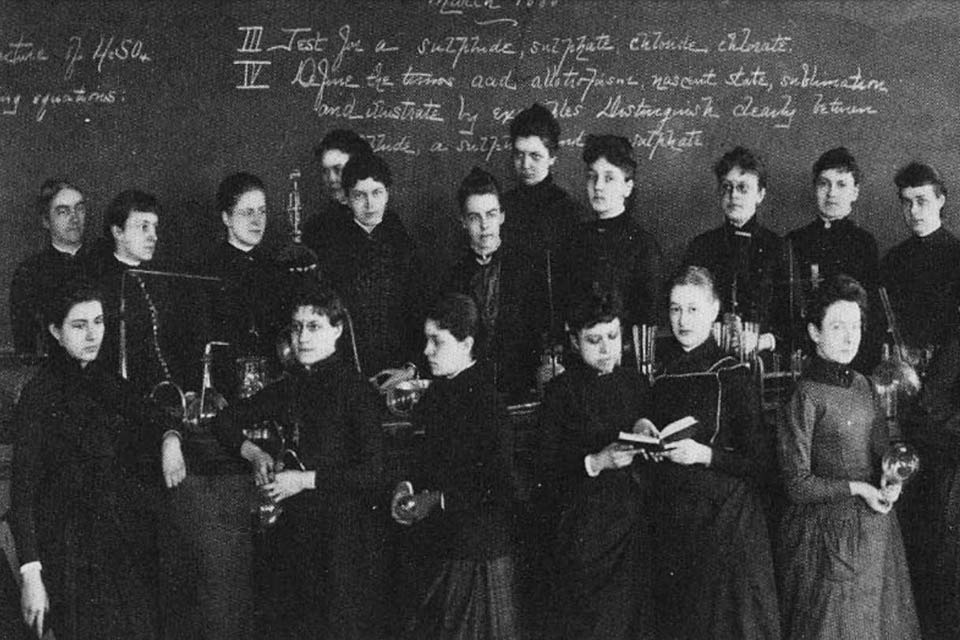

Women have been part of the field of landscape architecture from its U.S. origins in 1899 when Beatrix Farrand became one of the founding members of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). In fact, women-owned firms could be found in various regions in the country by the early twentieth century. Today, the role of women in the profession has grown such that women now make up the majority of both undergraduate and graduate students in university landscape architecture programs. However, they are not nearly as well represented at the professional level. As of 2018, only 35.5 percent of ASLA members, 30.4 percent of principals at landscape architecture firms, and 20.2 percent of ASLA Fellows were women.

The twelve Landslide 2020 sites are representative of a much larger story. While this report is issued on the centennial of the passage of the nineteenth amendment to the Constitution, it also coincides with nationwide social upheaval highlighting and addressing long-standing injustices and disparities. Within the profession, inclusion and equity for Black, indigenous, and people of color continue to be significant issues. ASLA notes that only one percent of its members identify as African American and four percent as Hispanic or Latino. ASLA provides resources to women and people of color in navigating the profession, in part, because of these discrepancies. Studies of roadblocks for women in the profession in the 1980s and again in the 2000s have consistently pointed to the incompatibility between this career and family life, an issue addressed in the Landslide video interviews with Martha Schwartz and Alison Hirsch. There are themes that certainly would have resonated with professional women landscape architects—many of whom never married or had children—more than a century ago. But life-work balance is only one issue in a complex web of equity concerns. As Heidi Hohmann, Director of Graduate Education in Iowa State’s School of Landscape Architecture noted in the January 2006 issue of Landscape Journal, women’s relationships with men in the twentieth-century landscape architecture workplace were “by turns abasing, pleasant, supportive, patronizing, and truly collaborative.”

In the exhibition’s introductory video, Thaisa Way provides a brief overview of women landscape architects in the twentieth century, while Alison Hirsch addresses her dual role as a mother of two young children and a university professor, and Sara Zewde speaks pointedly about being a Black woman in the profession. Landslide 2020 is, by design, not encyclopedic, but rather meant to spur greater inquiry and dialogue about women and landscape architecture, and hopefully to contribute to the broader conversation about diversity and inclusion.

The Landslide 2020 exhibition had originally been conceived as a traveling photographic exhibition that was to debut at the Boston Architectural College. However, the novel coronavirus pandemic necessitated a solely digital format. In the end, this constraint afforded a special opportunity: to feature richly produced Zoom interviews with some of the leading voices of the profession, many of whom contribute personal anecdotes about the featured designers and other insights. TCLF hopes that these rare recordings will serve as an inspiring and valuable resource for generations to come.