Situated at the southwestern tip of Manhattan along the Hudson River, the 92-acre mixed-use community of Battery Park City was built on landfill created from New York Harbor dredge and excavation materials from the World Trade Center site. Among its numerous parks, South Cove, designed by a multidisciplinary woman-led team, is a multi-level waterfront site offering unique second-story views of the Hudson River and is distinct for being associated with the primarily residential area of the development, as opposed to many of the sites which focus on commercial or civic programming. However, rising tides and the persistent threat of extreme flooding put this landscape, and the surrounding neighborhood, in jeopardy.

History

Situated at the southwestern portion of Manhattan along the Hudson River, just north of The Battery, after which the development was named, Battery Park City is a 92-acre mixed-use community that features numerous residential, commercial, and retail buildings alongside nearly 36 acres of parks and open space. The Battery Park City Authority (BPCA) was established by the New York State Legislature in 1968 to oversee its development, and the master plan for Battery Park City was created in 1979 by Stanton Eckstut and Alexander Cooper of Alexander Cooper Associates. Built almost entirely atop landfill created from dredging New York Harbor and the excavation of the World Trade Center site, the plan’s 26 parcels were designed independently by different developers in the 1970s and 1980s, creating a diverse neighborhood fabric that emulated the city’s mixed character.

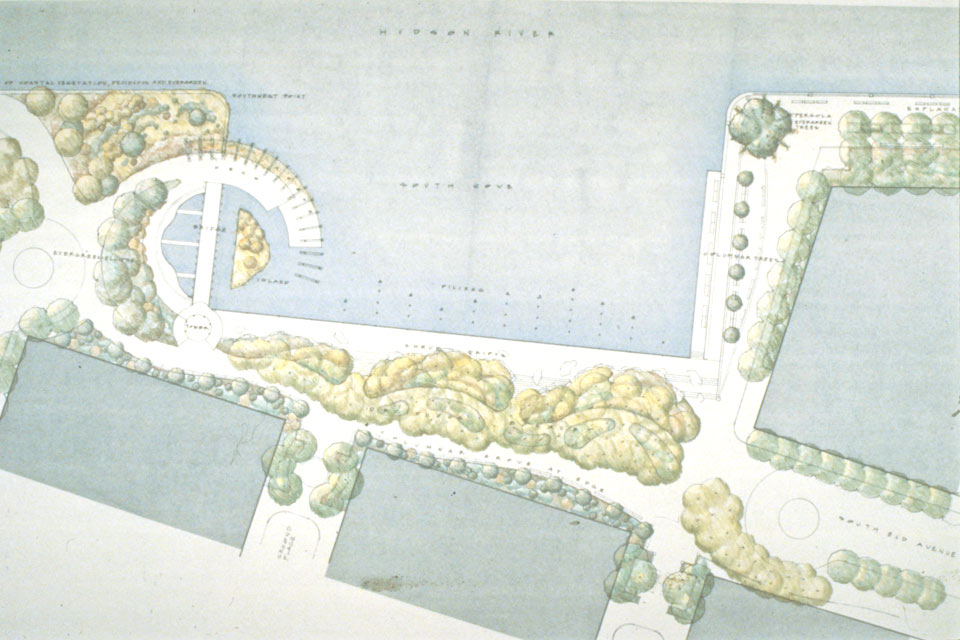

In 1984, BPCA hired a multidisciplinary team led by landscape architects Susan Child and Douglas Reed of Child Associates, with artist Mary Miss, and Stan Eckstut of the Battery Park City master plan team, to conceive of a 2 ½-acre park sited on a concrete platform jutting out over the water. They developed the concept of a cove with a visibly constructed edge, completing the project in 1987.

South Cove plan, New York, NY; image courtesy Doug Reed.

South Cove plan, New York, NY; image courtesy Doug Reed.

South Cove is considered one of Susan Child’s most significant works. Born in 1928, Child came to the profession of landscape architecture later in life. She graduated from Vassar College in 1950 with coursework in art history and French, and then moved to Boston, where she raised her family while participating in various art- and gardening-related societies and organizations. She frequently traveled to her father-in-law’s farm along the estuary of the Westport River in southeastern Massachusetts, a landscape that she cited as influencing her interest in and sensitivity to the built environment.

Child decided to pursue her passion for gardening and the allied arts through a graduate certificate in landscape and environmental design at the Radcliffe Institute in Boston in the early 1970s. She then worked for the City of Boston, managing “The Greening of Boston” Neighborhood Improvement Program and a number of Parks and Recreation Department projects, through which she cultivated an understanding of urban horticulture and city-based design. In 1978 she joined the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) Master in Landscape Architecture program, where she met classmate Douglas Reed, who later joined her firm as an associate and then partner.

After graduating from the GSD in 1981, Child formed her firm, Child, Hornbeck Associates, Inc., with Harvard professor Peter Hornbeck. The firm’s work extended across a number of typologies, from the preservation of historic designed landscapes, to civic, institutional, and residential projects of all scales. Extremely knowledgeable about site-specific plant materials, Child would add unique character to a landscape by utilizing a very limited number of plants in any one location. At South Cove, the team implemented this design ethos by selecting a palette of resilient plants that could withstand the site’s brackish and windy conditions. Beachgrass, beach rose, bayberry, and beach plum pervade the park, along with a locust grove--a tree tolerant of coastal conditions—sited further inland.

South Cove’s design was motivated by a number of specific site conditions that were unique to this artificially constructed land form. The design incorporates aspects of a natural cove, derived from the site’s topography, with the use of sparse vegetation by the shore, which becomes more dense further from the water. The 3.5-acre site mediates the topographical transition from city to river; boulders along the hillside lead down to The Esplanade, which runs the length of the Battery Park City waterfront. Referencing New York’s port heritage, blue ships’ lanterns hung on wooden lampposts line the Cove’s portion of The Esplanade and shimmer on the water at night. Wood pilings submerged in the river, the remnants of lost piers, continue the historical reference while drawing attention to the subsurface structure supporting the concrete cove.

South Cove is unique among Battery Park City’s many designed open spaces, as it is associated with the primarily residential area of the development, as opposed to many of the sites which focus on commercial or civic programming. As Douglas Reed frames it, the design team wanted to create “a more intimate place for families and people living in the area.” They sought to bring people closer to the level of the water, creating a space that feels removed from the dense urban fabric mere feet away.

South Cove was designed as a series of vertically layered spaces from which to explore this relationship between city and river’s edge. Miss’ site-specific installation, the form of which references the crown of the Statue of Liberty, leads visitors up an arched stairway offering sweeping views of the harbor. Entering the site from the north, The Esplanade wraps around through a grove of honey locusts at grade, while a second path gradually angles downward, leading to the water by way of a curved and wooden trellis-sheltered pier, which becomes partially submerged at high tide.

Threat

The threat of sea level rise is ever-present along the edge of the Hudson River, and in particular at South Cove, which was intentionally designed to descend to the existing water level. To date, South Cove has endured a number of significant storms, including Hurricane Sandy, during which the Hudson River overtook the curved edge of the park and encroached at the Esplanade level. Though the park has faced damages in these instances, and the wood pier, jetty, and trellis require periodic maintenance and replacement (due to saltwater erosion), South Cove has proved resilient, due in part to the meticulously selected plantings and purposeful boulder placement. As Reed notes, the challenge is not whether the park can survive its harsh site conditions, but how to retrofit the infrastructure of Battery Park City in order to protect the city further inland.

The Battery Park City Authority has created a Resiliency Action Plan that seeks to address this increasingly urgent concern. Having garnered $134 million in City bonds, the plan comprises multiple interrelated resiliency projects that aim to protect Battery Park City from the threats of storm surge and sea level rise. The three major components include the North Battery Park Resiliency Project, which constitutes a deployable barrier to protect the North Esplanade; the Battery Park City Western Perimeter Resiliency Project, which includes proposed garden/park walls that will reinforce flood protection along the water’s edge; and the South Battery Park City Resiliency Project, which intends to develop a continuous flood barrier that extends from the Museum of Jewish Heritage (adjacent to South Cove), through Wagner Park, across Pier A Plaza, to the edge of Historic Battery Park and through to a higher elevation point at State Street.

With plans developed since 2018, construction was set to begin in 2020; however, the pandemic and threats of major cuts to the City’s budget have pushed back this timeline. Reports indicate that construction may now start in 2021. Nevertheless, New York City cannot afford to wait.

What You Can Do to Help

Contact the Battery Park City Authority to urge them to move forward with their resiliency plans without delay and without having an adverse effect on South Cove, via email at info.bpc@bpca.ny.gov, or by mail:

200 Liberty Street, 24th Floor

New York, NY 10281

Walk The Esplanade from the north end of Battery Park City, along the river to South Cove, and experience the connection between city and water as the designers intended.

Get involved in participatory budgeting if you are a New York City resident, and encourage your City Council Member to allocate funds to your local park and citywide resiliency measures.