The Ford Foundation remains significant as the first large-scale interior atrium garden within the United States. One of many “firsts” that Kiley undertook in collaboration with architects Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo, the one-third-acre garden is set within the Ford Foundation’s glass, granite and Cor-ten steel headquarters building located in downtown Manhattan to the west of the borough’s historicTudor City Park. The Ford Foundation headquarters was one of several projects that architects Roche and Dinkeloo saw through to completion after the death in 1961 of their business partner, Eero Saarinen.

.jpg)

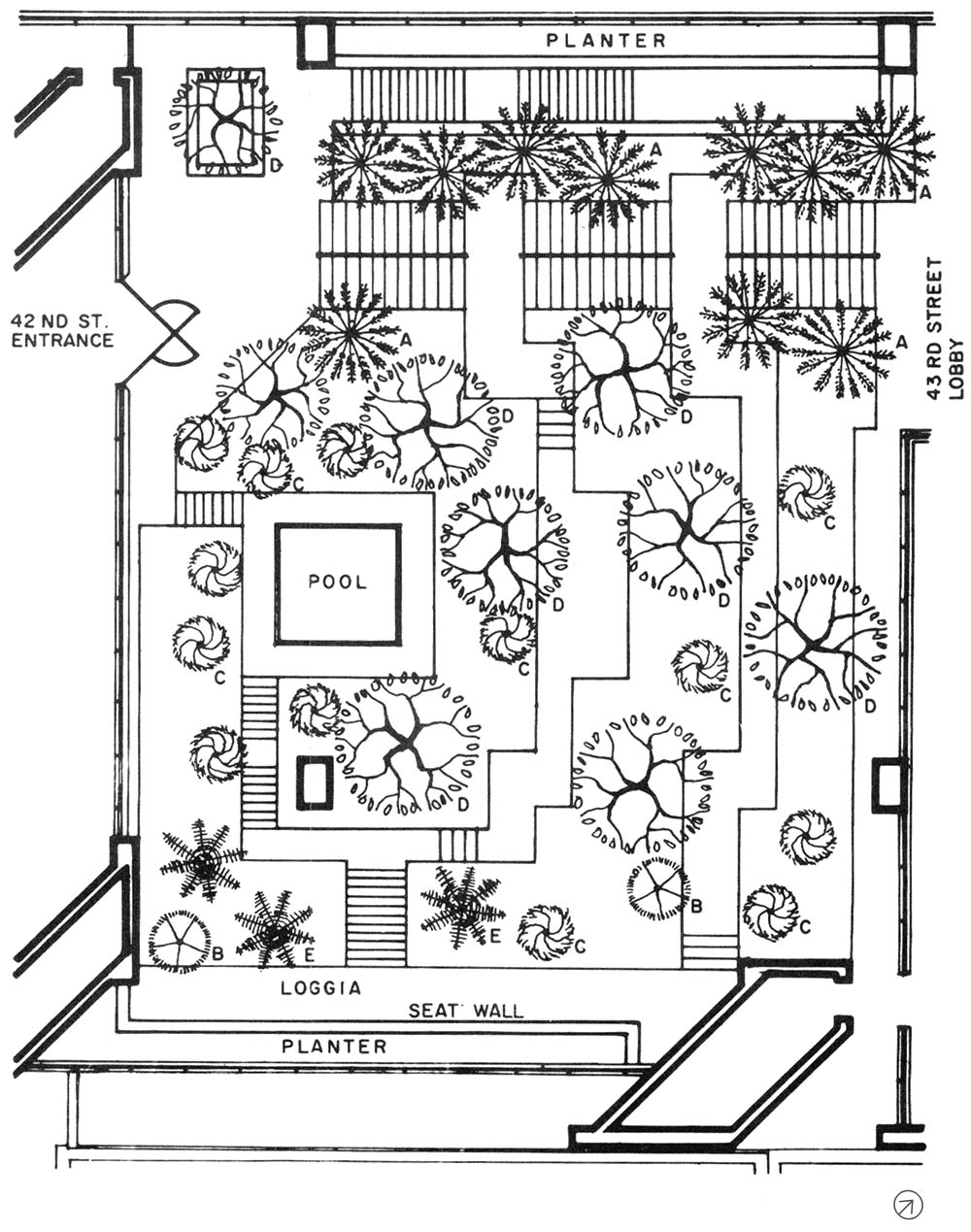

The core of the garden occupies an interior courtyard set within the building’s twelve-story, 160-foot high glass-walled atrium. Terracing is used to negotiate a 13-foot grade change from the building’s main entry on 42nd Street, and the secondary entry along 43rd Street. A primary staircase leading up from the 42nd Street entrance allows access to tiered garden terraces, which abut the wide granite stairs. In the interior of the garden, further terraces, granite steps, paths and planting beds delineate the space. A still, square pool of water, edged by a wide concrete band, provides a central focal element at the lowest level of the interior courtyard. Kiley utilized the entire atrium in his design reinforcing a connection between the courtyard and the offices, which overlook the atrium on the building’s north and west sides, by extending the garden upwards through the use of planters on the third, fourth, fifth and eleventh floors.

Using Fritz Wendt’s book on commercial agriculture as a resource guide, Kiley’s extensive and experimental planting scheme included nearly 40 trees, 1,000 shrubs and over 22,000 vines and ground cover plants. Eight 25- to 30-foot-tall southern magnolia trees, which Kiley had transplanted from Richmond, Virginia, served as the bones of the garden. Other trees specified for the space included jacaranda – used to create an allée alongside the 42nd Street staircase – evergreen pear, red ironbark and Japanese cryptomeria. Camellias, six varieties of evergreen azalea bushes and Japanese andromeda were planted in masses below the trees, beneath which ornamental ferns and grasses, baby’s tears, mondo grass, Korean grass, roundleaf fern, tassel fern, and mother spleenwort formed a lush groundcover. Flowering vines included herald trumpet, San Diego red bougainvillea, creeping fig, and blood trumpet vine. Seasonal beds and planters also allowed for a variety of blooming plants in the garden, which were periodically changed out to add variety.

Using Fritz Wendt’s book on commercial agriculture as a resource guide, Kiley’s extensive and experimental planting scheme included nearly 40 trees, 1,000 shrubs and over 22,000 vines and ground cover plants. Eight 25- to 30-foot-tall southern magnolia trees, which Kiley had transplanted from Richmond, Virginia, served as the bones of the garden. Other trees specified for the space included jacaranda – used to create an allée alongside the 42nd Street staircase – evergreen pear, red ironbark and Japanese cryptomeria. Camellias, six varieties of evergreen azalea bushes and Japanese andromeda were planted in masses below the trees, beneath which ornamental ferns and grasses, baby’s tears, mondo grass, Korean grass, roundleaf fern, tassel fern, and mother spleenwort formed a lush groundcover. Flowering vines included herald trumpet, San Diego red bougainvillea, creeping fig, and blood trumpet vine. Seasonal beds and planters also allowed for a variety of blooming plants in the garden, which were periodically changed out to add variety.

Like the courtyard planting beds, the graduated planters on the building’s upper floors (the widest on the third floor and the narrowest on the fifth) were planted with trees, bushes, vines and groundcover. Kiley added several new specimens to the planting palette including: Kafir plum; the flowering vine, Henderson allamanda; Irish moss; and tufted woodfern. In the eleventh floor planter, Kiley used Indialaurel fig trees surrounded by Sprenger asparagus.

The installation and maintenance guidelines, which were created for the site, would later serve as a model for Kiley’s future projects. At the Ford Foundation, lighting, irrigation, drainage and other details were meticulously measured and calibrated. The project, which was completed in 1967 and later in 1997 named a New York City Landmark, was both a success and a failure. Many of Kiley’s plantings failed to thrive in the unique environment, and were later replaced with subtropical plantings better able to adapt to the temperate climate inside the glass walls. Unfortunately some of those plantings fail to honor Kiley’s vision – diverging dramatically in form, scale and texture from those originally specified. Plantings within the space would benefit from better maintenance and the replanting of more appropriate species, with plant materials which better reflect the original design intent. These small improvements paired with greater information about the design on the Foundation’s Web site would play a substantial role in educating the public about Kiley, his design approach, and Modernist landscape architecture, ensuring the future of the landmark design.

The installation and maintenance guidelines, which were created for the site, would later serve as a model for Kiley’s future projects. At the Ford Foundation, lighting, irrigation, drainage and other details were meticulously measured and calibrated. The project, which was completed in 1967 and later in 1997 named a New York City Landmark, was both a success and a failure. Many of Kiley’s plantings failed to thrive in the unique environment, and were later replaced with subtropical plantings better able to adapt to the temperate climate inside the glass walls. Unfortunately some of those plantings fail to honor Kiley’s vision – diverging dramatically in form, scale and texture from those originally specified. Plantings within the space would benefit from better maintenance and the replanting of more appropriate species, with plant materials which better reflect the original design intent. These small improvements paired with greater information about the design on the Foundation’s Web site would play a substantial role in educating the public about Kiley, his design approach, and Modernist landscape architecture, ensuring the future of the landmark design.

Joe Karr, FASLA, 2013

The interior garden occupied about one quarter of the floor plan and the full twelve story height of the Ford Foundation building. The Office of Dan Kiley collaborated with the architects, Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo Associates, while also working together on the Oakland Museum simultaneously. It was convenient because meetings in the architect’s office, especially during the design phase, usually involved both projects.

Dan and I were already familiar with working with Kevin and his staff because the Ford Foundation project (1964-1967) started about a year after the Oakland Museum (1962-1968) had begun. The Ford Foundation garden was complex because there was a 13-foot drop in elevation from one side to the other in the garden space, which resulted in a series of stairs and steep 2 to 1 slopes throughout the garden. The working models in Kevin’s office were extremely important because the architects and we could make design changes there, during the meetings, on the primary model by cutting pieces of chipboard, placing them in the model, and immediately seeing how design revisions affected the garden space three dimensionally. That process reduced the number of revised drawings that we needed to prepare in our office and exchange back and forth with the architects for review and comment.

Initially, we began designing a tropical garden but soon realized that we would have to use temperate plants because of single glazing and other factors affecting relative humidity in the 120-foot high garden space. At that time there was very little information available regarding the use of temperate plants inside. We had to experiment and the client accepted the challenge. The major trees became 35 foot high Southern Magnolias. They were necessary to give immediate scale to the garden even though they only reached to the fourth floor of the twelve story high garden space.

Dan’s keen design sense and special presence always brought the best architects seeking his talents. The process of working with Dan and Kevin on this project from design through construction gave me a unique experience that I always cherished and was later able to apply to numerous interior garden designs in my own office.

.jpg)