-

In late 1962, architects Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo were hired to design a new modern home for the Oakland Museum of California that would house the city’s collections in the art, sciences and natural history. They had recently taken over the firm created by Eero Saarinen, who died unexpectedly in 1961. Dan Kiley, who had collaborated on numerous projects over the previous fifteen years with the Saarinen office, including the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial (site of the Gateway Arch), was enlisted as the landscape architect. In envisioning their design for the museum, Roche and Dinkeloo came up with a unique plan – to create a building that would serve the dual purpose of museum and public park. They proposed the construction of a five-acre building topped by a rooftop garden, set within a seven-acre footprint. It was an ambitious undertaking recalled Joe Karr, a landscape architect in Kiley’s office who worked on the project from 1963 to 1968: “Roof gardens such as the Kaiser Center in San Francisco and Constitution Plaza in Hartford had been completed earlier. However, they were both much smaller.”

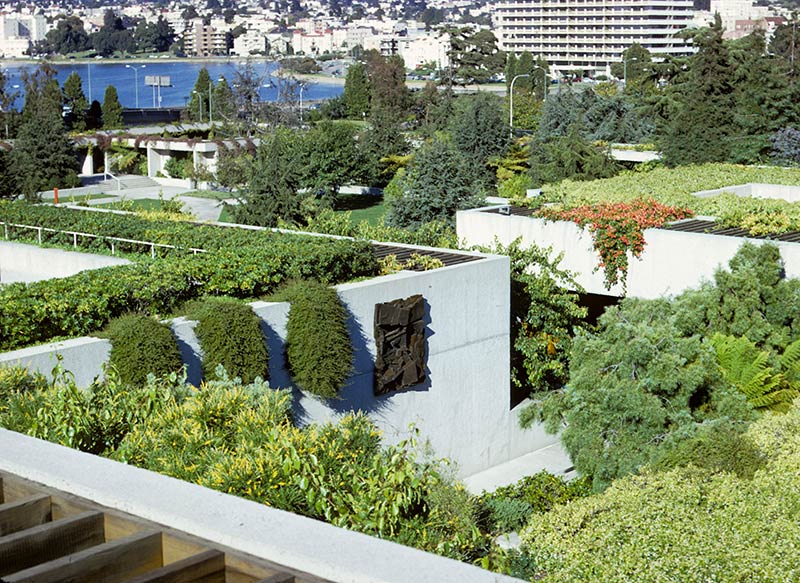

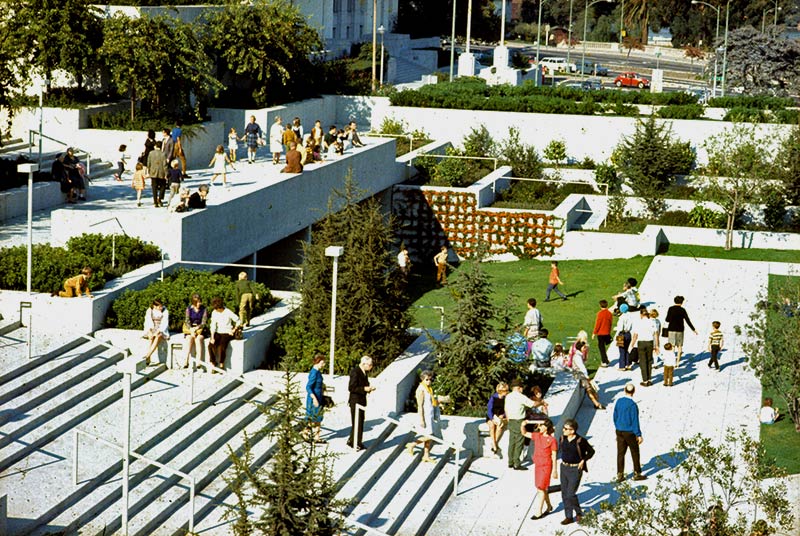

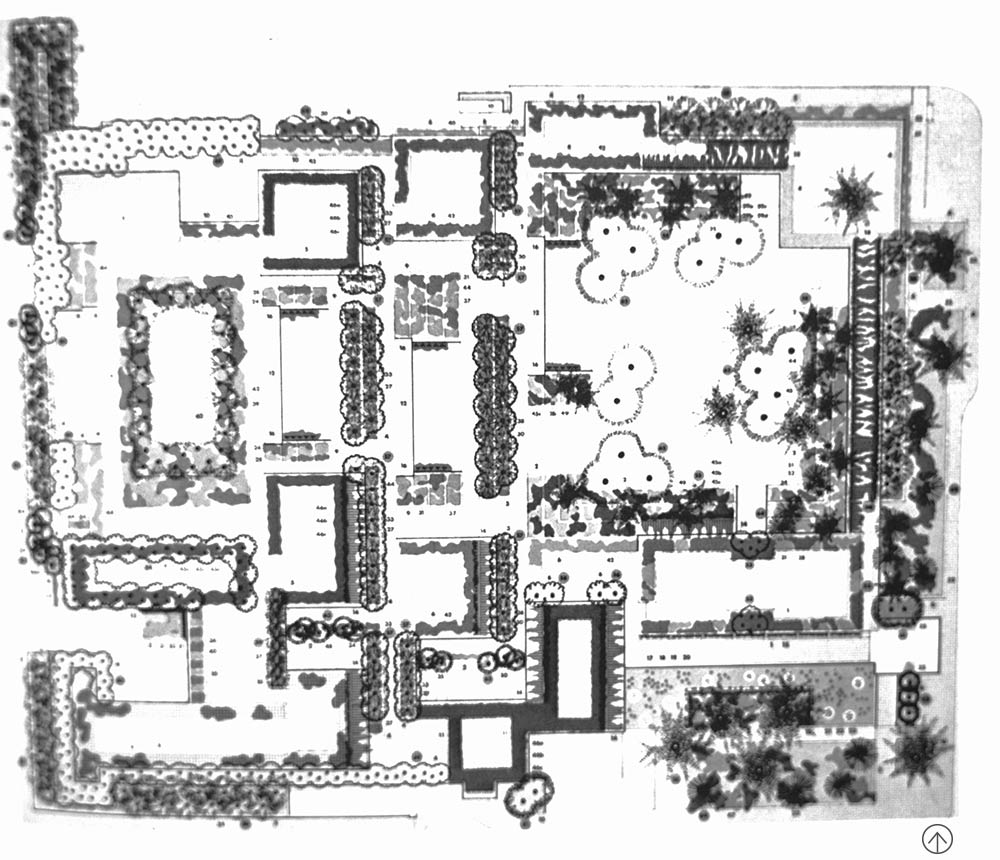

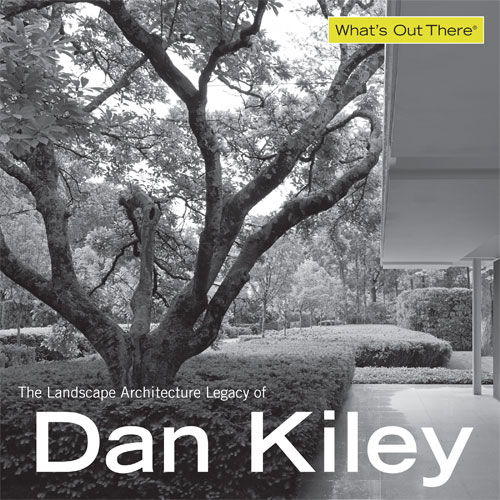

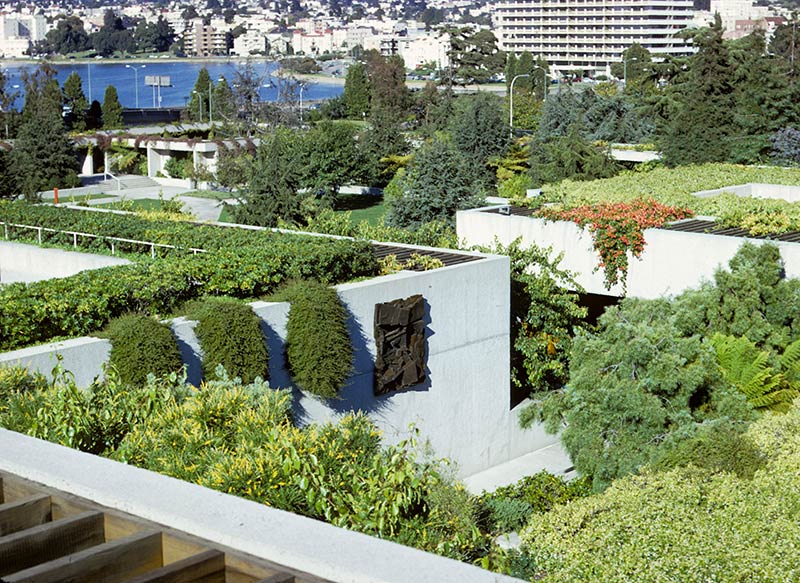

Roche and Dinkeloo created a structural framework for the gardens, developing a stepped landscape of concrete planters, stairs and terraces. Atop each of three levels of galleries, the design team set aside space for a rooftop garden with each gallery level opening up onto the roof of the gallery below. These garden levels were intended to serve both as public gathering areas and as an extension of the museum’s exhibition space which could house a portion of the outdoor sculpture collection. Karr said: “There were nearly 180 individual planters forming the roof garden. Each contained its own set of plants with common physical requirements for life and growth. “At the garden’s lowest level the architect’s designed a large central gathering space – the only portion of the site located at grade. The garden contains a single water feature at the southeastern corner of the site, a narrow, rectangular Koi pond.

Kiley collaborated with landscape architect Geraldine Knight Scott to select the plantings for the project. Scott, who was a founding member of the California Horticultural Society, was known for her horticultural expertise. Texture, color and form were used to determine their selections, which help to break-up the site’s rigid geometry. Specimen plants were used to highlight key circulation routes, and provide points of interest. The architects envisioned a densely planted urban oasis, which was achieved through close spacing of the specified plantings. Kiley and Scott’s plant selection included blooming plants, vines, shrubs and a selection of both smaller and larger trees.

Kiley collaborated with landscape architect Geraldine Knight Scott to select the plantings for the project. Scott, who was a founding member of the California Horticultural Society, was known for her horticultural expertise. Texture, color and form were used to determine their selections, which help to break-up the site’s rigid geometry. Specimen plants were used to highlight key circulation routes, and provide points of interest. The architects envisioned a densely planted urban oasis, which was achieved through close spacing of the specified plantings. Kiley and Scott’s plant selection included blooming plants, vines, shrubs and a selection of both smaller and larger trees.

“Dan, as always, had the total concept clearly in his mind,” noted Karr. “The selection of the trees was most important for him because they formed the basic structure from which the rest of the garden design evolved. His knowledge of plants and how they could be used with architecture was remarkable.” Large trees, which include eucalyptus, live oak and several pre-existing cedar of Lebanon trees, were planted exclusively on the lower level (the only portion of the garden not on-structure), around a central lawn panel. In the rest of the garden, smaller trees were planted in straight rows in tiered planters and reflect Kiley’s tendency to group trees of the same type, often in bosques, rows and allées. These include a combination of fruit trees (olive, lemon and Japanese pear); evergreen (pine); and deciduous (hawthorn). As an early roof garden the project held a number of unique challenges. Plantings for the site were selected for their tolerance of the arid climate, and their ability to survive with the limited root space offered by the planters (the on-structure planters were limited to a depth which ranged from 8 inches to 3 feet). The landscape architects needed to account for drainage, irrigation, and other issues. In order to ensure the plantings longevity, special care was taken in order to meet the basic requirements of the different plants, which were grouped according to their needs. A special soil mix was created to fill the planters (UC Mix #6) and automatic systems were installed to provide the plants with adequate food, water and fertilizer.

High walls around the exterior perimeter of the gardens, as well as tall plantings give the space a sense of isolation from the surrounding urban context. Viewers, met with the vertical concrete walls of the museum’s first story, obtain glimpses of the garden through hints of plantings which spill over from concrete planters. From the raised interior of the garden, views out towards Lake Merritt help connect the museum to the city’s further vistas while maintaining its separation from the adjacent street. The overall effect, according to Karr, was transformational: “The Oakland Museum structure and its overlaying landscape were uniquely interwoven together as one … [and] appeared as an extensive multi-level garden rather than a building.”

High walls around the exterior perimeter of the gardens, as well as tall plantings give the space a sense of isolation from the surrounding urban context. Viewers, met with the vertical concrete walls of the museum’s first story, obtain glimpses of the garden through hints of plantings which spill over from concrete planters. From the raised interior of the garden, views out towards Lake Merritt help connect the museum to the city’s further vistas while maintaining its separation from the adjacent street. The overall effect, according to Karr, was transformational: “The Oakland Museum structure and its overlaying landscape were uniquely interwoven together as one … [and] appeared as an extensive multi-level garden rather than a building.”

In recent years many of the plantings have been renewed, and a great number of the sculptures within the garden have changed. While some of the more recent plantings were not the original genus and species that were specified in Kiley and Geraldine Knight Scott's original design, the replacement plant materials have honored and reinforced historic visual and spatial relationships, while still employing a palette of blooming plants, vines, shrubs and a selection of both smaller and larger trees that were a hallmark of the original design.

-

Joe Karr, FASLA, 2013

Dan had many collaborations with Eero Saarinen and Associates over the years. After Eero’s untimely death in 1961, Dan continued the relationship with that office, which was later renamed Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo Associates. The first major project directly with Kevin Roche was the Oakland Museum which began in late 1962. At the outset, during early design, Dan consulted with local Berkeley landscape architect Geraldine Knight Scott for west coast technical advice. There was little knowledge or experience available at that time regarding the technicalities inherent in designing and constructing large scale landscapes over structure.

Dan had many collaborations with Eero Saarinen and Associates over the years. After Eero’s untimely death in 1961, Dan continued the relationship with that office, which was later renamed Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo Associates. The first major project directly with Kevin Roche was the Oakland Museum which began in late 1962. At the outset, during early design, Dan consulted with local Berkeley landscape architect Geraldine Knight Scott for west coast technical advice. There was little knowledge or experience available at that time regarding the technicalities inherent in designing and constructing large scale landscapes over structure.

The Oakland Museum was a monolithic structure comprising four city blocks in area with a continuous landscape covering its entire roof surface. Roof gardens such as the Kaiser Center in San Francisco and Constitution Plaza in Hartford had been completed earlier. However, they were both much smaller. The Oakland Museum structure and its overlaying landscape were uniquely interwoven together as one. From the outside it appeared as an extensive multi-level garden rather than a building.

Dan never hesitated in letting young landscape architects in his office take on full responsibility for a project under his leadership even when he was away from the office for days, or even weeks, at a time attending meetings for other projects across the country.

I began working on the project in spring 1963, just into the early design phase, and carried it through to completion in 1968. In order to quickly learn California plants, I ordered cut sheets from Sunset Magazine dating from the late 1950s to the early 1960s. Each issue contained numerous heavily illustrated articles on different plants and how they were incorporated into California gardens. I assembled lists of plants with the same requirements for light, exposure, soil mix, soil depth, drainage, irrigation, fertilizer, etc. There were nearly 180 individual planters forming the roof garden. Each contained its own set of plants with common physical requirements for life and growth. The overall tapestry of plants, and the landscape design, was developed in that way with occasional double checking with Geraldine for accuracy.

Dan, as always, had the total concept clearly in his mind. The selection of the trees was most important for him because they formed the basic structure from which the rest of the garden design evolved. His knowledge of plants and how they could be used with architecture was remarkable.

I later used the experience gained from this project when designing roof gardens in my own practice. I also recalled how solutions to design problems could be achieved by utilizing working models like those in Kevin Roche’s and Dan’s offices. More importantly, I learned from Dan about the oneness of architecture and landscape and how each is an extension of the other.

-

Oakland Museum of California. “Architecture + Gardens,” http://www.museumca.org/architecture-gardens.

Hilyard, Gretchen, “Hidden Histories: The Oakland Museum of California.” Spur, http://www.spur.org/blog/2011-06-02/hidden-histories-oakland-museum-california.

Liw, Jennifer and Chriss Patillo, “Historic American Landscapes Survey: Oakland Museum of California (Oakland Museum),” 2005, http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/ca/ca3600/ca3624/data/ca3624data.pdf.

White, Josephine, “A 1969 Oakland Museum Gets $62m Renovation,” Adobe Airstream, May 2010, http://adobeairstream.com/design/a-1969-oakland-museum-gets-62m-renovation/.

Hill, Angela, “The reinventing of the Oakland Museum of California,” Oakland Tribune, April 25, 2010, http://www.insidebayarea.com/oaklandtribune/localnews/ci_14933461.

Kiley, Dan and Jane Amidon. Dan Kiley: The Complete Works of America’s Master Landscape Architect (Boston, New York, London: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 60-65.

“Landscape Design: Works of Dan Kiley.” Process: Architecture 33. (Tokyo: Japan, Process Architecture Publishing Co., 1982), 68-74.

Kiley, Dan, “The Landscaping.” In The Oakland Museum: A Gift of Architecture, (Oakland, CA: Oakland Museum Association, 1989).

The Cultural Landscape Foundation. “What’s Out There: Oakland Museum of California,” http://tclf.org/landscapes/oakland-museum-california.