-

When it opened in 1965 the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, with its signature Gateway Arch, became an instant classic.This milestone collaboration between Kiley and architect Eero Saarinen was one of their first, and it was one of the last to come to fruition.

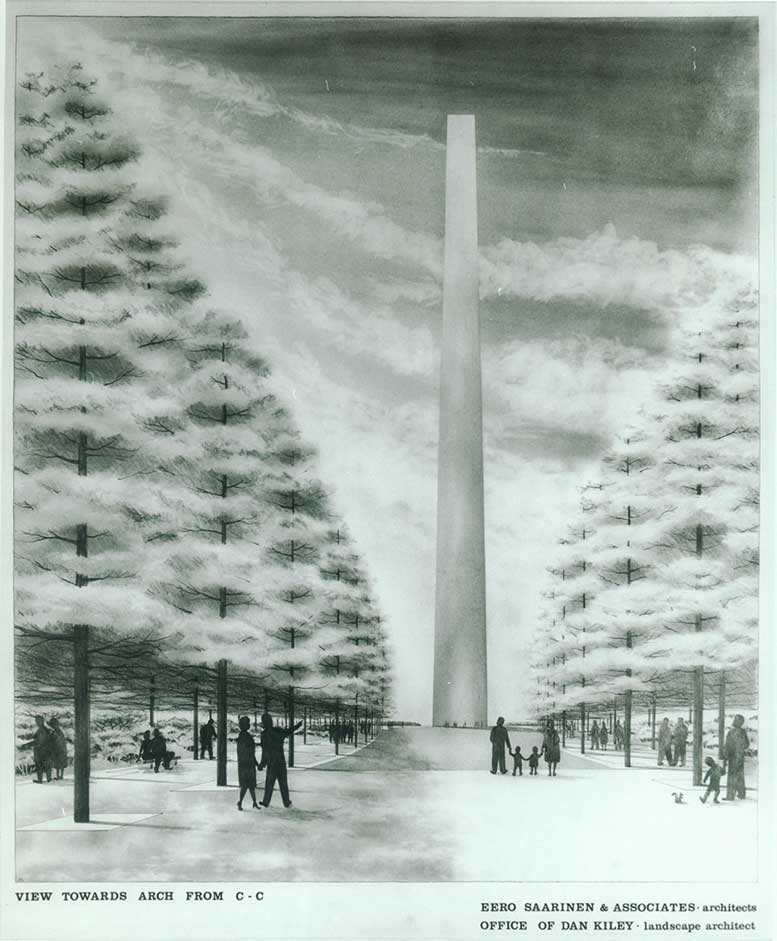

In 1947 a design competition was held fora new memorial that would sit on a 91-acre site along the banks of the Mississippi River in St Louis, MO. The memorial would commemorate the 1804 departure of Lewis and Clark’s expedition and highlight St. Louis’ role in westward expansion. For this first large-scale Post War competition, Eero Saarinen formed a team with himself as lead designer, Dan Kiley as landscape architect, and Jay Henderson Barr as associate designer. Rounding off the team were artists Lily Swain Saarinen and Alexander Girard. Their winning design for the memorial was selected from a pool of 172 entries.

In 1947 a design competition was held fora new memorial that would sit on a 91-acre site along the banks of the Mississippi River in St Louis, MO. The memorial would commemorate the 1804 departure of Lewis and Clark’s expedition and highlight St. Louis’ role in westward expansion. For this first large-scale Post War competition, Eero Saarinen formed a team with himself as lead designer, Dan Kiley as landscape architect, and Jay Henderson Barr as associate designer. Rounding off the team were artists Lily Swain Saarinen and Alexander Girard. Their winning design for the memorial was selected from a pool of 172 entries.

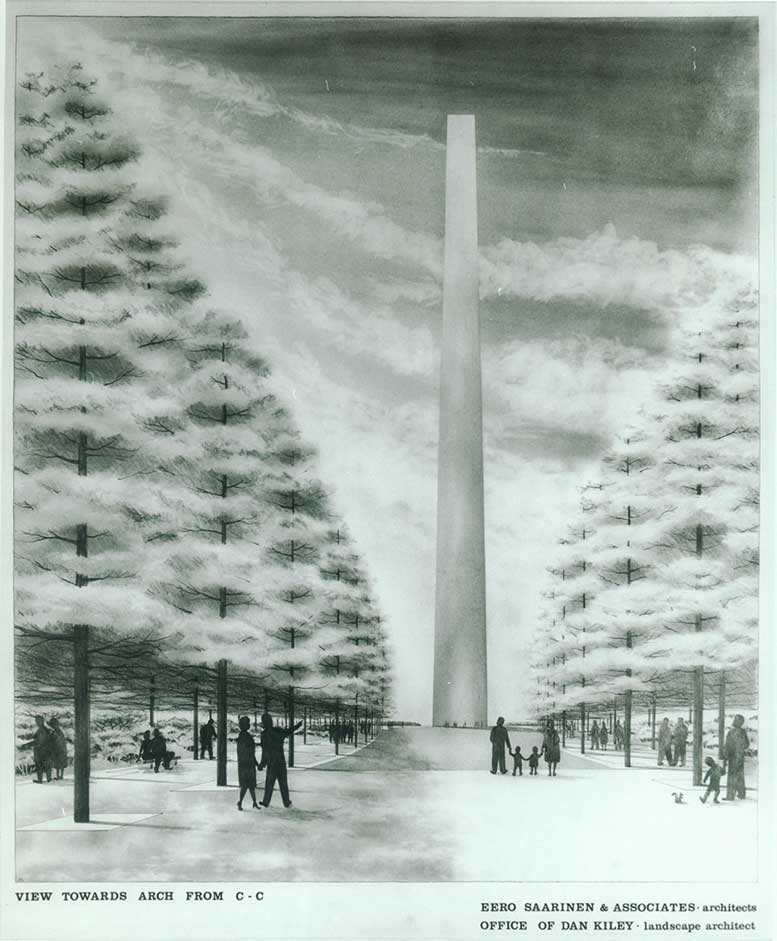

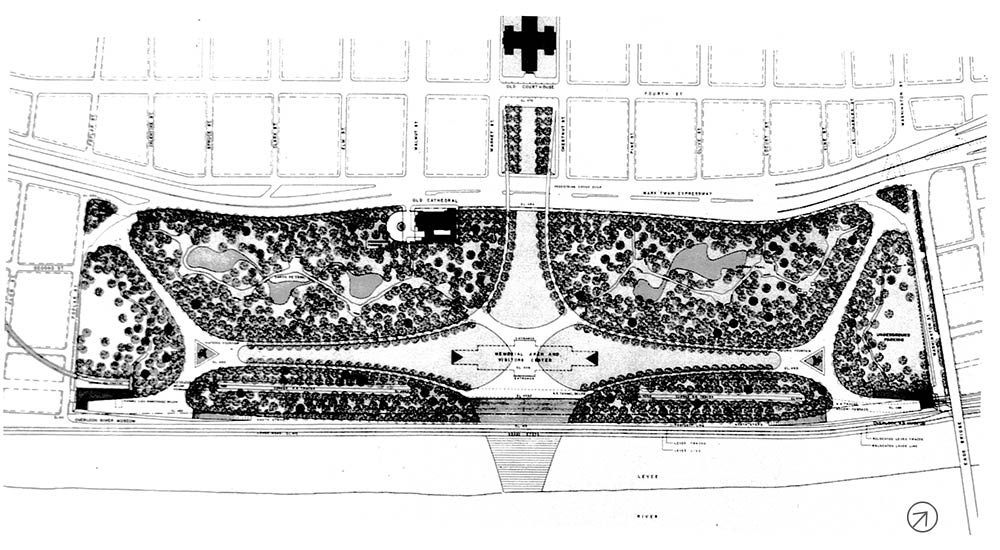

Kiley and Saarinen spent thirteen years producing design drawings - from 1948 until Saarinen’s death in 1961 - and Kiley continued the process with Saarinen’s office until 1964. Their original drawings and competition entry proposed an urban forest of densely nestled trees beneath the curve of Saarinen’s stainless steel clad arch.The final design, however, differed dramatically in the look and feel of its landscape – a naturalistic rendering of curvilinear ponds, groves of trees, and an expansive allée, three trees deep on each side of a wide walk. This curving aperture serves as the backbone of the site, set beneath Saarinen’s monumental 630-foot-tall gateway. The final concept takes into account axial site lines between the Gateway Arch and the Old Courthouse and repeats the sweeping curve of the arch in walkways, stairs, and site walls.

The planting plan for the landscape is characteristically Kiley – a limited planting palette, tightly-packed, evenly-spaced trees along the walks (Kiley specified the use of 900 tulip poplars for the allée), and a transition from formal to informal landscape, with groves of trees and shrubs that gather at the edges of the lakes and lawn. Kiley considered the arcing bands of tulip poplars to be the most significant part of his design, saying in a 1982 publication: “My basic interest in the landscape was to develop a sense of movement of spatial continuity. This was done by arranging undulating lines of high tulip poplar trees spaced very close together so they started from either entrance wide and narrowed down to a neck, and then as one turned to the side elevation of the arch, the trees would widen up to the base.”

When Kiley’s involvement in the project ended in 1964, the National Park Service assigned staff landscape architects to develop construction drawings and implement the plan. While construction of the arch was completed in 1965, the landscape was implemented in phases between 1971 and 1981, held up by funding shortages. Several alterations were made to Kiley and Saarinen’s approved design; most significantly, the 900 tulip poplars specified by Kiley were replaced with 900 Rosehill ash trees, a tree with a distinctly different form. Additionally, only half of the trees that Kiley and Saarinen’s plan massed along the lawn areas were planted. Even with these challenges, the site has received much recognition, with listing on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 and designation as a National Historic Site in 1987.

Cultural Landscape Reports (CLRs) were created for the site in 1996 and 2010, which identified its condition and state of decline (including more than 150 missing trees in the allées) and also made recommendations for rehabilitation. At the forefront of both CLRs is the notion of adhering to Saarinen and Kiley’s design intent and the integration of the arch and landscape as one seamless memorial. Triggered by a new NPS General Management Plan,a design competition was launched at the end of 2009 and awarded to a team led by landscape architects Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates Inc. Their concept both respects Kiley’s design intent (for example, his monoculture trees planted in allées three rows deep along the walks) and envisions a more accessible landscape that is better integrated with its urban surroundings. Significantly, the National Park Service is actively working with local and state municipalities, businesses, and foundations on the CityArchRiver 2015 program, a public-private partnership that holds the Van Valkenburgh plan at the center of a strategy to revitalize downtown St. Louis and the adjacent waterfront. The design is slated for completion in 2015, although funding shortages may cause delays. In April 2013 St. Louis City and County passed a parks proposition that would raise $30 million each year to benefit the memorial and other regional parks and greenways.

1 Process: Architecture 33

: Landscape Design: Works of Dan Kiley. Inchinowatari, Katsuhiko, ed. (Tokyo: Japan, Process Architecture Publishing Co., 1982), 109.

-

Michael Van Valkenburgh, FASLA, 2013

In 1973, after graduating college, I won a Dumbarton Oaks Garden Traveling Fellowship, based on a proposal to visit Dan Kiley’s built work. My plan was to first visit Kiley’s office (Dan forgot I was coming and was not there), and then travel across the US, immersing myself in his projects. Ten years later, I researched, curated, and wrote the catalogue for an exhibition of modern and proto-modern gardens, which included his work. Although he intimidated me at first when we finally met face to face, I was deeply inspired by the series of discussions with Dan that I undertook as part of the research for the show.

Given this longstanding enthusiasm for his work, and knowing his strong opinions, I was a bit daunted about the idea of preserving, but also transforming, the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial (JNEM), which is the impetus behind the CAR2015 project in St. Louis, which my office is currently spearheading. Ironically enough, I had skipped the JNEM in my cross-country trip, because it was under construction at the time and fell outside of my study focus of “built work.”

As a project that lingered in the design stage for almost 20 years, and underwent multiple revisions, the JNEM is an interesting lens for understanding Kiley’s evolution as a designer. For instance, Kiley’s competition entry for the JNEM represents the idea of national expansion as a walk through a natural landscape of forest and meadows. In this early work, he was using the idea of the natural systems as a kind of scenographic story-telling device, which runs counter to the way that we normally think of his work.

Dan’s thinking about the project changed over the years, and he was ultimately not involved in the implementation of the JNEM, which further complicates attempts to understand and honor his design legacy there. For instance, the Processional Walk allées were planted with a monoculture of ashes, rather than a species from Dan’s shortlist of preferred trees.Now with the imminent approach of the Emerald Ash Borer, these trees need to be replaced. As we undertake this task, I have kept in mind Dan’s concerns that I would ruin Harvard Yard by replacing the failing monoculture of elms with a mixed species planting that had similar spatial characteristics, but greater environmental resilience. Although I disagreed with him about the Yard, I can’t argue with him on his own turf; my admiration for him is just too strong and I want to preserve his vision as best we can. We will be sticking with a monoculture for the Processional Walks at the JNEM, this time with London plane trees.

Elizabeth K. Meyer, FASLA, 2013

The Jefferson National Expansion Museum grounds are haunting and haunted. The triple rows of trees, aligned along catenary-arcing paths, flow across 91 acres of billowing topography toward the magnificent steel arch designed by Eero Saarinen; they refer to an absent landscape--the expansive space of American’s westward expansion made possible by Thomas Jefferson’s “Louisiana Purchase.” St. Louis, located on the western banks of the Mississippi River, was a portal to the vast, audacity of the continental interior. This park of undulating waves of topography, located at this territorial threshold, has buried secrets as well as absences: a underground museum, sunken railroad lines, and the ruins of 40 city blocks of cast iron and brick warehouses that were demolished in order to build this memorial. The actual urban precinct that sold settlers goods, provisions, and services for their months’ long travels across the prairies, is but a memory.

Kiley himself is elusive at times. He worked on this masterwork of modernism for over 15 years; yet the extent landscape is considerably different in materials and details from Kiley’ early drawings. Still, reminded of the first time I walked the memorial grounds before I knew much about it, I recall the feeling of being transported to a vast, scaleless, disorienting, at times sublime, placelessness. This may be mid-twentieth century landscape architecture’s most important public space and most bizarre modernist space. It is in this perception and experience of space, the spatial analog of “a walk through the woods, ” that Kiley’s hand still haunts the memorial grounds. The rhythmic cadence of the stately trees—and the parallax created when walking through them and over billows of topography revealing and concealing interstate highways, bridges, the river, and the rail—creates a palpable threshold, a liminal experience, between the everyday city and the arch. The spatial effects of the constructed landscape are fundamental to the memorial experience of the arch. As Saarinen and Kiley agreed, “all parts of the an architectural composition must be part of the same form world.” Space was the formal medium that joined the ground, plants, water, concrete and metal together, that differentiated them from the adjacent city, and that afforded hints and allusions to the distant territory. Haunting and haunted. Thick space on cleared ground. A masterpiece of modernism emerges from the ruins of modernization. Projects like this remind me of how much I dig landscape. Does it get any trippier than this?

-

National Park Service. “The Significance of the Gateway Arch Landscape,” http://www.nps.gov/jeff/planyourvisit/the-significance-of-the-gateway-arch-landscape.htm.

The Museum Gazette. “Landscaping the Gateway Arch Grounds.” http://www.nps.gov/jeff/historyculture/upload/landscaping_the_arch_grounds.pdf.

Gateway Arch Experience. “About: Arch Facts & FAQ,” http://www.gatewayarch.com/experience/arch-facts-faq/.

Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates Inc. “Projects: Jefferson Nat’l Expansion Memorial,” http://www.mvvainc.com/project.php?id=74.

Landscape Voice. “Jefferson National Expansion Memorial,” http://landscapevoice.com/jefferson-national-expansion-memorial/.

Bellavia, Regina M. and Gregg Bleam. “Cultural landscape report for Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, St. Louis, Missouri.” National Park Service, Great Plains Systems Support Office, Cultural Resources. 1996.

“Landscape Design: Works of Dan Kiley.” Process: Architecture 33. (Tokyo: Japan, Process Architecture Publishing Co., 1982), 109-113.

Daniel Urban Kiley: The Early Years, ed. William S. Saunders (New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999).

The Cultural Landscape Foundation. “What’s Out There: Jefferson National Expansion Memorial,” http://tclf.org/landscapes/jefferson-national-expansion-memorial.