Alfred Caldwell Biography

Alfred Caldwell (1903 - 1998) was the last Prairie School landscape architect but his career transcended the design of landscapes. He was also a poet, civil engineer, architect, city planner, philosopher, and distinguished professor of architecture during his long life of 95 years.

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, on May 26, 1903, Caldwell was the third of six children of Joseph and Emma "Kitty" Davis Caldwell. His family moved to Chicago, Illinois, in 1909, where Alfred grew up in poverty. Fueled by his French-American mother who insisted that he read and memorize poetry and history, Caldwell became a thinker and a dreamer early in his life. He entered the University of Illinois in 1921 to study landscape architecture but never completed his studies there.

In 1923, he eloped with his cousin, Virginia Pullen, to whom he was married for 65 years until her death on September 2, 1988. Shortly after they married, they returned to Chicago, where Caldwell took up a landscape practice in partnership with George Donoghue, who later became superintendent of the South Chicago Park District. Here Caldwell worked on small buildings and landscape projects.

A family friend, Charles Terrel, suggested that he apply for work with the famous Prairie School landscape architect Jens Jensen. Jensen had been superintendent of Union Park and Humboldt Park in Chicago, founded the Friends of Our Native Landscape in 1913, designed landscapes for the wealthy, and he became Caldwell's mentor. Between 1924 and 1929, Caldwell completed various jobs for Jensen, including landscapes for the Harley Clarke house in Evanston, Illinois (1925), the Harold Florsheim house in Ravinia, Illinois (1927), and the Edsel B. Ford house, in Grosse Pointe Shores, Michigan (1926-1932). During this period Caldwell also began his publishing career with his first article, "In Defense of Animals" (1931), which appeared in Jensen's journal, Our Native Landscape. Caldwell and Jensen became fast friends, and they carried on an extensive correspondence until Jensen's death in 1951.

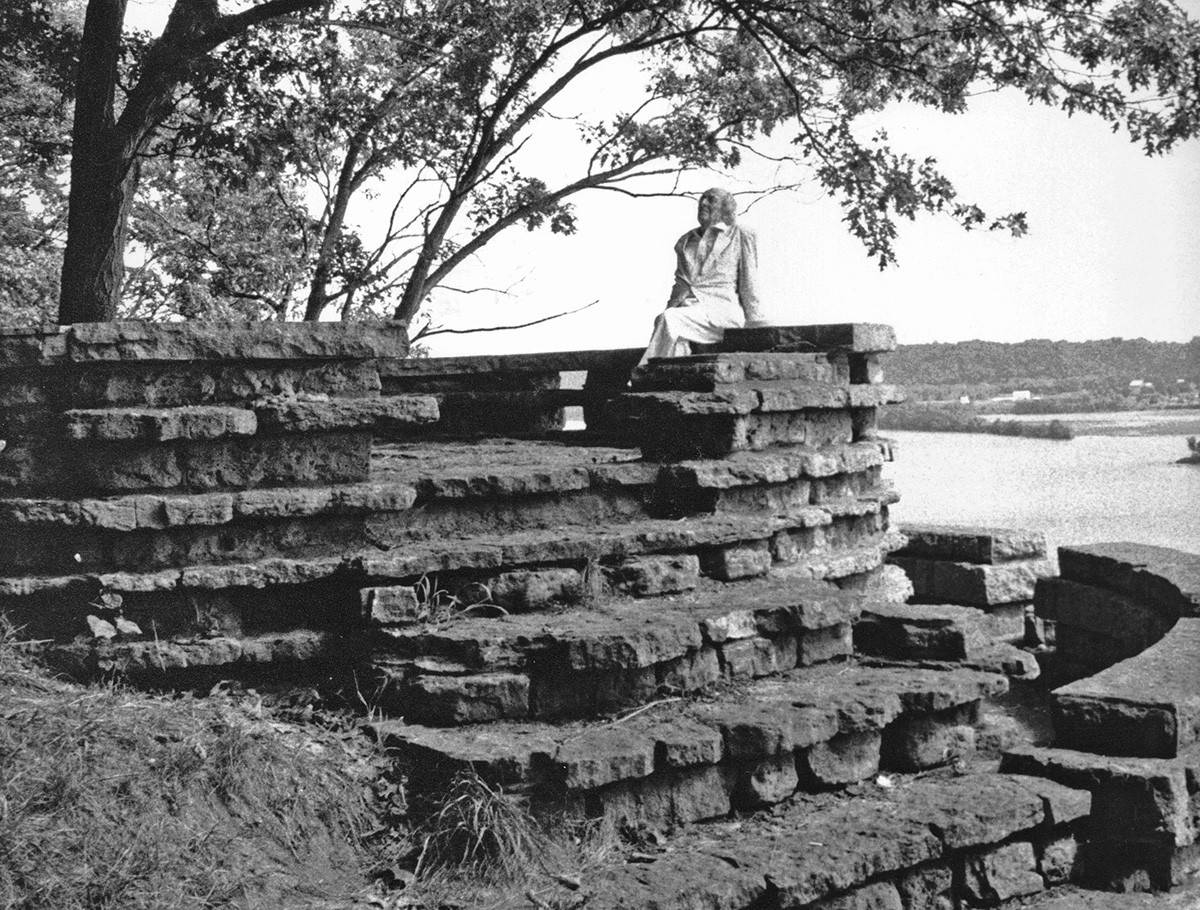

In 1927, Jensen commended Caldwell to Frank Lloyd Wright, whom Caldwell visited several times at Taliesin and who implored Caldwell to join him in his endeavors at Spring Green. Caldwell, like Jensen and Wright, was an independent, fiery genius and showman, and while Caldwell did not accept this invitation, Wright's organic ideas strongly influenced Caldwell's subsequent architecture, especially Caldwell's pavilions and landscape for Eagle Point Park in Dubuque, Iowa. Eagle Point Park won a national W.P.A. design award in 1936, and Franklin Delano and Eleanor Roosevelt visited the site during the 1936 presidential campaign. Upon seeing Caldwell's work, President Roosevelt remarked that "this is my idea of a worthwhile boondoggle." Caldwell was subsequently fired from this job, just as he would be fired from most of the jobs he would ever have.

Upon returning to Chicago with his family, Caldwell was hired by George Donaghue as a senior draftsman in the Chicago Park District where he worked until 1940. Caldwell was a prodigious worker, possessed masterful drawing abilities, displayed a thorough knowledge of indigenous plants, and created large sets of landscape drawings for Montrose Park, Northerly Island, Promontory Point at Burnham Park, Jackson Park, Riis Park, and the Lily Pool at Lincoln Park.

On a fateful afternoon at the Lily Pool in 1938 that would begin a long relationship and a turn in his career, Caldwell became acquainted with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Walter Peterhans, and Ludwig Hilberseimer. Mies, the most famous of the Bauhaus modernists who had come to Chicago to found the school of architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology, asked Caldwell through Peterhans if the Lily Pool was the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. The Lily Pool left a lasting impression on Mies, and Mies remembered Caldwell when he graded the drawings that Caldwell submitted as part of his architect's examination in 1940. Caldwell's work was so good that Mies asked him to make drawings for Hilberseimer, who needed illustrations for the books he was writing on city planning. Caldwell's drawings appeared in Hilberseimer's The New City (1944), The Nature of Cities (1955), and Entfaltung einer Planungsidee (1963). Mies and Hilberseimer, who spoke little English at that time, also found Caldwell on numerous occasions to be a perfect speech maker for them. At the end of World War II, during which Caldwell worked as a civil engineer for the War Department, Mies hired Caldwell as the first full-time American faculty member at the architecture school of Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) Mies granted Caldwell a Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1945 and, in 1948, Caldwell completed a Master of Science in City Planning under Hilberseimer. Mies assigned Caldwell to teach the second and third year of architectural construction and architectural history. Caldwell taught these courses from 1945 to 1960, thus having a powerful influence on the postwar generation of Chicago architects.

During this period he also completed a number of landscape projects. Caldwell's landscape for Lafayette Park (1955-1963), an urban renewal housing project near downtown Detroit that Mies designed with the developer Herbert Greenwald, was considered a model for urbanization. Today, its owners covet Lafayette Park, more because of the lush landscape in an urban setting than because of the modern building design. During this period Caldwell also continued to publish his philosophical essays on landscape and city planning including "Atomic Bombs and City Planning" (1945), which appeared in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects.

Caldwell resigned his professorial position in 1960 to protest Mies' dismissal as architect of the IIT campus. This frivolous gesture led, however, to another significant job, this time as head of a special projects office at the Chicago Department of City Planning. As the "commissioner of faith," Caldwell chaired a think tank that developed projects for Mayor Richard Daley's political machine. Caldwell continued his private landscape practice during this period, and the most notable of his projects was the landscape for Lake Point Tower (1965-68) in Chicago. His outside design work, as well as his unrelenting blistering critiques of Chicago's urban renewal projects, got Caldwell fired, again.

This created an opportunity for the School of Architecture at the University of Southern California (USC) to hire Caldwell, who was perfectly suited to bring clarity and purpose to architectural education during the turmoil and dissonance of the Vietnam War. Caldwell introduced himself as the original hippie who had worn bell-bottom pants in the 1930s, was a member of Chicago's avant garde Dill Pickle Club, and was, according to Mies, a leftist, although never a card-carrying communist. Caldwell taught construction, philosophy, literature, and history within his fifth-year design studio, and most of the students gravitated to him. In contrast, Caldwell was unpopular with the faculty, although one of his biggest supporters was Craig Ellwood, the California architect of the Miesian school. Caldwell worked with Ellwood on many projects.

Caldwell's most important southern California work was the prairie school landscape for Arts Center College of Design in Pasadena with Eric Katzmaier whom he also advised on the design of Central Park at Huntington Beach that was constructed according to Prairie School principles. Professor Caldwell was retired at USC in 1972 in spite of strong student protest.

During this time, Caldwell continued to write essays, most of which were published over the next thirty years in the art and architecture journal, The Structurist. While in southern California, Caldwell also took up poetry writing again, producing number of sonnets.

Caldwell never believed in retirement, and he pursed his creative work until the end. At the age of 78, Caldwell returned to IIT as the “Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Professor of Architecture,” and he taught there until he died. The Chicago Chapter of the American Institute of Architects gave him their Distinguished Educator Award in 1980, the Associated Collegiate Schools of Architecture named him Distinguished Professor in 1985, and IIT bestowed him with a Doctor of Humane Letters degree in 1988. He continued to develop a superb Prairie school landscape on his farm in Bristol, Wisconsin, until his death in 1998.

Bibliography

Blaser, Werner. Architecture and Nature: The Work of Alfred Caldwell. Basel: Birkhäuser, 1984.

Domer, Dennis, Editor. Alfred Caldwell: The Life and Work of a Prairie School Landscape Architect. London and Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

Wilson, Richard Guy. "An Artist and a Poet, Alfred Caldwell Illuminates Nature's Ways." Landscape Architecture, September 1977, 407-12.

About the Author

Dennis Domer is an Associate Professor Emeritus in American Studies and an Associate Dean Emeritus in the department of Architecture & Urban Planning at the University of Kansas.