Alfred Yeomans Biography

In the early 1900s, Yeomans (1870 - 1954) helped to fashion the resort community of Southern Pines in the North Carolina Sandhills out of the dusty remains of its lumber and turpentine industry past.

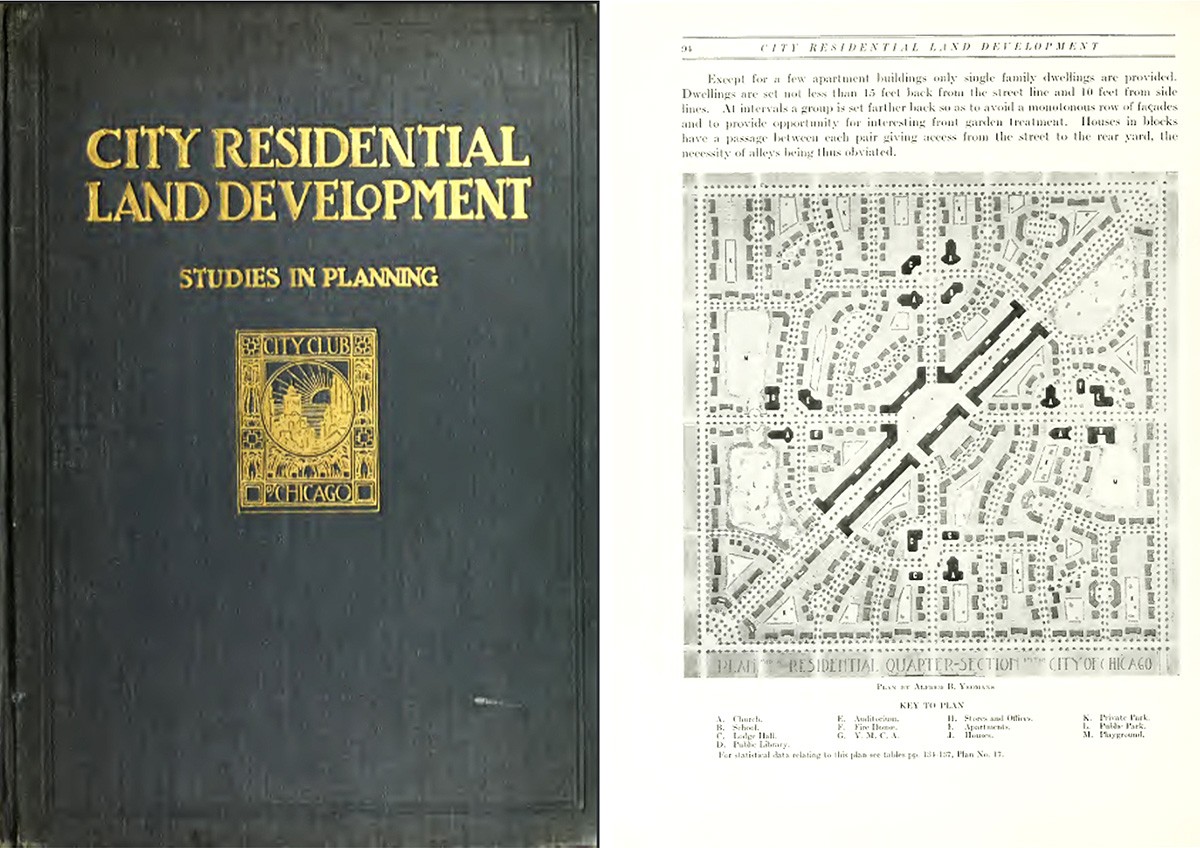

Alfred Yeomans is a relatively obscure figure in the annals of American landscape history. The younger brother of landscape architect Louisa Boyd King, Yeomans is best known for his suburban designs in the Chicago area where in 1916 he edited "City Residential Land Development: Studies in Planning: Competitive Plans for Subdividing a Typical Quarter Section of Land in the Outskirts of Chicago." Well-known today for its beautifully rendered, non-competitive plan by Frank Lloyd Wright, Yeomans' preface to this publication suggests that “the environs of our large cities constitute one of the most promising fields for the work of the city planner.” Although this competition would give Yeomans a platform in the urban area, perhaps his greatest work was in the North Carolina Sandhills, where in the early 1900s he helped to fashion the resort community of Southern Pines from the dusty remains of a lumber and turpentine industry outpost. In this neighboring town to the Village of Pinehurst, Yeomans guided landscape design in a patchwork of efforts spanning nearly half a century.

Yeomans was born in Orange, New Jersey, in 1870, the third of five children of Reverend Alfred Yeomans and his wife Elizabeth Ramsay Yeomans. He graduated from Princeton University in 1891. And with no strong leaning in any one area, Alfred occupied himself with traveling while exploring a variety of professions including teaching, publishing, and social work. By 1902, he had discovered a fascination for landscape architecture. So at age 32, he began working towards a career in the field, eventually practicing in Chicago. This interest brought him to Southern Pines around 1904 when he was called upon by his uncle, Pennsylvania industrialist James Boyd, to create a landscape plan for his Weymouth estate on a pine-covered ridge just east of town.

When Yeomans first arrived in the town, the region was trying very hard to overcome the devastations of post-Civil War clear-cutting, that by the turn of the 20th century had left a wasteland. Laws passed in the late 19th century prohibiting the mutilation of any tree, plant or shrub within town limits were not enough to stop the leveling of the woods across the surrounding countryside. The Boyd's 2500 acre estate included the region's largest vestige of the original longleaf pine forest that once covered the southeastern coastal plain, with many of the pines marked with V-shaped cuts etched into their trunks by former slaves and their descendants to let loose the flow of sap collected for turpentine, pitch and rosin.

The first task of importance for Yeomans at Weymouth was to produce a topographical map of the tract and a study to determine the character of the houses to be built and of the surrounding grounds and gardens. The original plan included a sixteen acre park, tennis courts, a croquet lawn, a practice golf course, stables, and riding rings. Roads corresponding to the elevations of the ridge were laid out to suit the topography, all a continuation of the town street system. Yeomans' emphasis was on native flora along with naturalized drought-tolerant ornamentals to create a type of garden that blended seamlessly with nature. This planting strategy proved very compatible with the extreme environmental conditions of the longleaf pine ecosystem and, by 1910, Weymouth was reported to be one of the largest and finest estates in North Carolina.

On the east edge of the Weymouth tract was a former tar and turpentine plantation, the circa 1850 Duncan Shaw House. At the farmstead, Yeomans encountered the plain-style aesthetic that was characteristic of district's founding Highlanders. Yeomans supervised the restoration of the long-neglected buildings, creating a caretakers cottage for the estate. He became a student of local history, ultimately facilitating the preservation of several regional historic sites. Yeomans' work in the Sandhills reflects the same dignity of restraint exhibited by the native culture, and his designs in the region appear natural enough to have arisen within the vernacular.

Commissioned by the Boyd's to plan the Weymouth Heights subdivision, Yeomans' layout featured curving streets that wrapped around large landscaped, wooded lots. In addition to his work with landscape, Alfred was a self-taught architect of buildings, and he designed numerous houses in Weymouth Heights. The centerpiece of the development was the Highland Pines Inn, designed by New York architect Aymar Embury II, with Yeomans planning the hotel setting. Another important project for Yeomans involved the creation of the initial layout for the Knollwood subdivision that was located between Pinehurst and Southern Pines. At Knollwood, he worked in cooperation with landscape architect Warren Manning in the review and development of the road system between the two communities. The personal correspondence of Pinehurst Resort owner Leonard Tufts indicates that, at one time, Yeomans may have been employed by Warren Manning.

Inspired in part by concepts introduced at the Boyd estate, Southern Pines residents engaged in a series of a landscape initiatives that over time lead to the emergence of the town as a leading "garden place" in the state. Alfred Yeomans continued to guide these efforts after he became a full-time resident in 1918. Servings for years as a town commissioner and on various civic committees, he devoted his life to the creation a well-defined landscape identity for the resort.

His writings and designs reveal the influence of landscape architect O.C. Simonds with whom Yeomans had been associated in Chicago. Nowhere is this more apparent than at Mt. Hope Cemetery, the Southern Pines municipal graveyard that Yeomans created with his re-design of an 18th century burying ground established at one of the highest points along the spine of hills where the town was founded. The plan included a series of stepped terraces with flat markers that surround the simple sandstone slabs that originally crowned the hill. On this knoll, native hollies, cedars, dogwoods, and longleaf pines line winding paths in a natural park-like setting. Yeomans is buried on the northeast side of the cemetery, in a grove of trees that faces the village center nearly two hundred feet below.

Since the time of his death in 1954, many aspects of Alfred Yeomans work have fallen into neglect, or have been overwritten and erased. An almost forgotten figure in the resort town he helped to create, hope for the survival of his remaining designs rests on public education about their artistic and cultural value, and of the landscape that made Southern Pines famous for gardens featuring natural beauty.

About the Author

Ray Owen is a board member of the Friends of Weymouth and The Classical Design Foundation. He is a lifelong resident of Southern Pines, North Carolina.