Artist Mary Miss' Statement about "Greenwood Pond: Double Site"

Mary Miss

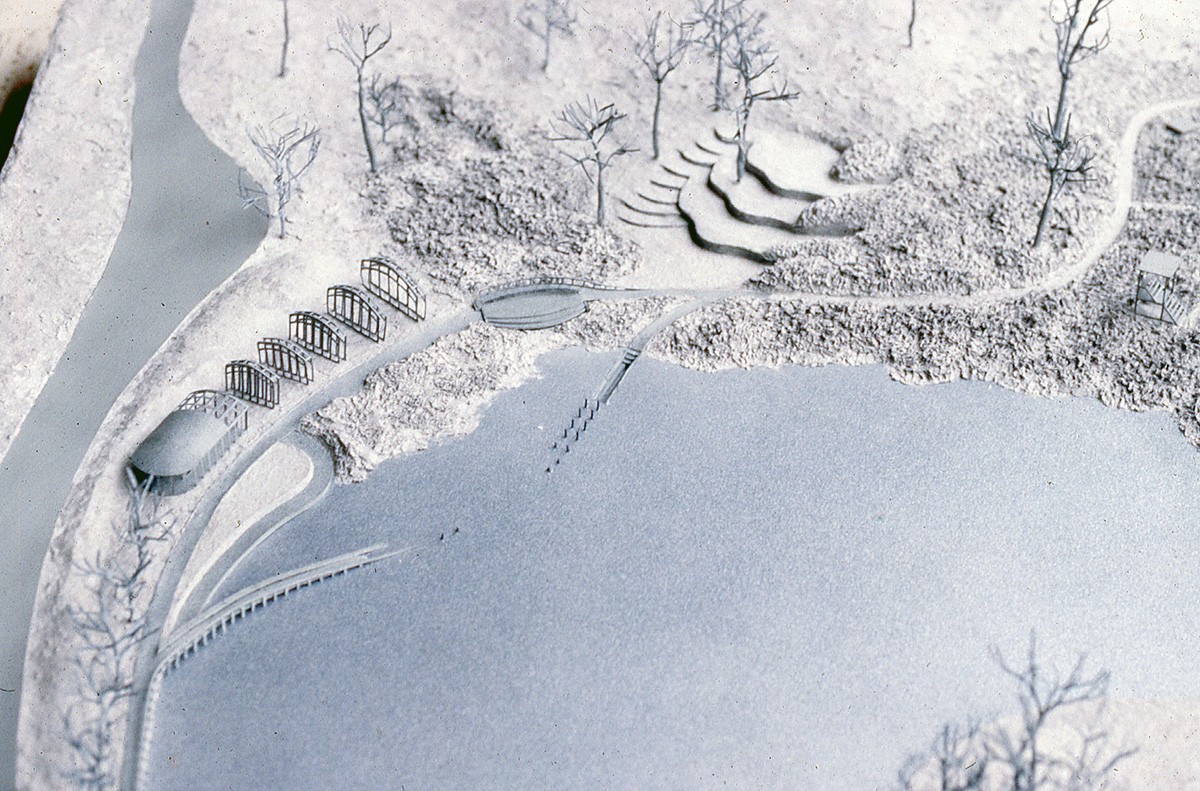

Greenwood Pond: Double Site

Des Moines Art Center

1989-1996

I was invited to the Des Moines Art Center by Julia Brown Turrell in the late 80s to find a site for a project on the grounds of the museum. This was part of a program Turrell initiated for a series of artists to do site specific works at the museum. This was a different way of thinking about sculpture and its context that both she and I were interested in.

Rather than place a sculpture as an object in the landscape, how could a work take the site, its history, ecology, social nature into consideration? And how could a museum begin to operate outside its walls, find new ways of involving people with art who might never step inside a museum? These were issues that were important to the museum at this time.

I quickly focused on the derelict Greenwood Pond. Beyond that act of engagement that was so compelling to me, I was particularly taken with the idea of how this silt filled pond that was a socially problematic area for the community could be transformed into a demonstration wetland that would be a destination.

My research was assisted by Jessica Rowe’s collection of historical information and an introduction to the indigenous communities of the area by Gaylord Torrence. I also became aware of the fact that a huge percentage of the state of Iowa had been tiled and drained for agricultural use and that only a small percentage of the original wetlands remained. This has resulted in periodic devastating flooding in the state. Touring wetlands around the area with a botanist from Iowa State University, Arnold van de Valk, I began to become familiar with what grew and lived in these areas and how they functioned.

It took seven years working with the museum, the surrounding community members, the garden club, the city parks department and the Science Center to complete this work.

To have a work of mine owned by such a well-regarded institution as the Des Moines Art Center, was hugely significant for me. As the only large scale sited work of mine that is owned by a museum to date, it is particularly important. It is my understanding that the mission of museums is to steward the works in their collection and that this was therefore a permanent part of that collection.

This work is particularly important to me in other ways. This initiated my practice of collaborating with scientists that has become central to my ongoing work with the City as Living Laboratory (CALL), a non-profit I went on to found in 2009. It was during the development of this project, when I began gathering such rich information, that I became interested in finding ways to ‘decode’ the natural systems and infrastructure that surround us. How to give access to the layers of history and content that make a place?

This project in Des Moines is key to the continued development of my work—it’s where this more direct engagement with communicating problems in the environment starts. In particular, the direct engagement of communities and the desire to find ways to give insight into the landscape around us and its relationship to the built environment are at the heart of the work I do with CALL.

I believe that today, as the multiple questions surrounding climate change overwhelm us, this project is more important than ever. It gives people a chance to directly get a sense of the this important aspect of the Iowa landscape, its wetlands. Also, it puts the museum in a leadership role as a cultural institution helping to address the complex issues of our times. It features the role of women artists in giving a more intimate sense of our relationship to the land. And it shows that artists don’t always have to be kept offside—they can have an essential role in our public realm along with educators, scientists and policy makers in taking on these problems.