To Be Real...You've Got to Be Real

If you think disco diva Cheryl Lynn is about to pop up and start singing "... to be real" everywhere you go, it's probably because the concept of authenticity is now almost ubiquitous as a brand attribute, personality description, advertising slogan and travel experience.

Indeed, authenticity is not just for Civil War re-enactors and department store Santas anymore. According to Stephanie Rosenbloom's September 11, 2011 New York Times Cultural Studies column, "legions of marketers and social networking coaches are preaching that to succeed online -- on Twitter, Facebook, Match.com -- we must all 'be authentic!'" Celebrities and politicians she writes, including Michele Bachmann, Hillary Clinton, Anderson Cooper, Katie Couric, and Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York, also claim or strive to be authentic. And, a Google search yields 59 million results (and two Wikipedia pages) for the word authenticity.

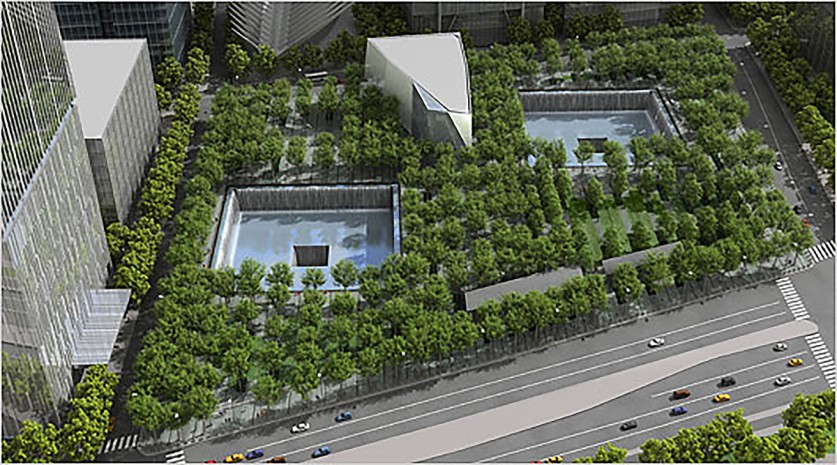

Two new sites in New York -- the 9/11 Memorial and the newly relocated home of Alexander Hamilton -- definitely raise questions about authenticity in the context of how we may manage a landscape's transformation. One of the iconic remnants of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in southern Manhattan was the "Survivors' Staircase", the last visible above ground level structure at the World Trade Center site. The protection of this tangible connection to the dead, the survivors and our collective national grief, was just a few years ago the subject of impassioned concern voiced by many including the Preservation League of New York State, the World Monuments Fund, the Municipal Art Society, the New York Landmarks Conservancy and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which in 2006 listed it among America's 11 Most Endangered Historic Places. Yet, in 2008, the staircase was moved. Though it will be part of a future 9/11 Memorial Museum, one has to ask, what happened to concerns for its presence in situ, once deemed so important? Astonishingly, none of the recent 9/11 Memorial critical evaluation by architecture or landscape architecture critics raises this issue.

The same week the 9/11 Memorial opened, in the aptly named Hamilton Heights neighborhood in northern Manhattan, the National Park Service completed a five-year, $14.5 million dollar restoration of the Alexander Hamilton home (known as the Hamilton Grange National Memorial). Twice previously moved, it was relocated to a former meadow in St. Nicholas Park. In this case, what passes for authenticity might charitably be called truth adjustment.

Edward Rothstein, consistently one of the nation's most thoughtful cultural critics, chronicled the site's saga for the New York Times. The house, designated a national memorial in 1962, was raised with hydraulic lifts and rolled around the corner to its current location in 2008. Rothstein spends considerable time on Hamilton the man, and the National Park Service's efforts that have "taken much care to temper the orthodoxies of restoration - which, in some historic homes, now leave everything in authentic, unrestored condition." Rothstein writes the house has been rotated from its original position, "but it if hadn't been reoriented, the view of the house from West 141st Street would have been of its undistinguished rear than from its front façade." Rothstein opines, "No better setting could now be imagined for Grange." This raises two questions: 1. Can we move around historic buildings like chess pieces? (try that one with the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association); and, 2. As usual, what about that landscape the house was dropped into? Does it have no significance? No discussion of that.

St. Nicholas Park, constructed in 1906, was designed by landscape architect Samuel Parsons, Jr., a protégé of Calvert Vaux and landscape architect for the New York City Department of Parks for more than thirty years, and is his most significant design in New York City.

Repeat, this is Parsons' most significant design in New York City. Saying "most significant" about a historic building to edi-fixated preservationists would trigger a battle cry, but historic landscapes don't seem to merit the same.

As with the Olmsted and Vaux design for Central Park, Parsons' made one think the park had sprung from Nature. In 1910, Parsons wrote that his design intent was to move visitors "through a rocky defile and again creeping along the base of a cliff with grassy slopes falling away below." That intent, and the only open meadow in the park is now gone -- forever defiled is the most intact and authentic Parsons-designed landscape in New York City.

So what happens when we subtract a significant extant landscape feature from its authentic setting or add one to a landscape that has significance of its own? What are the implications of introducing historic features that give a false sense of history? How do we measure success? What criteria should we apply? What happens when the site's programming dictates our decisions? Rothstein concludes, "The measure of the Grange's success will not be in its use of appropriate moldings or plantings." Agreed, but the authenticity of our shared cultural landscape -- from works by master designers to hallowed ground where significant events transpired -- should be recognized, understood, valued and, where appropriate, safeguarded.

This Birnbaum Blog originally appeared on the Huffington Post on October 7, 2011.