The Big Pre-Oscar Snub

Who got snubbed? That’s the question asked every year when the Oscar nominees are announced. Critics opine about the performances not recognized? And gossips wonder if those snubbed had meltdowns like the one comedic genius Catherine O’Hara’s character Marilyn Hack has in the brilliant satiric movie For Your Consideration (O’Hara, by the way, was snubbed for that performance. Sad!).

Well, it’s not Oscar season but we already have one of the biggest snubs of the year.

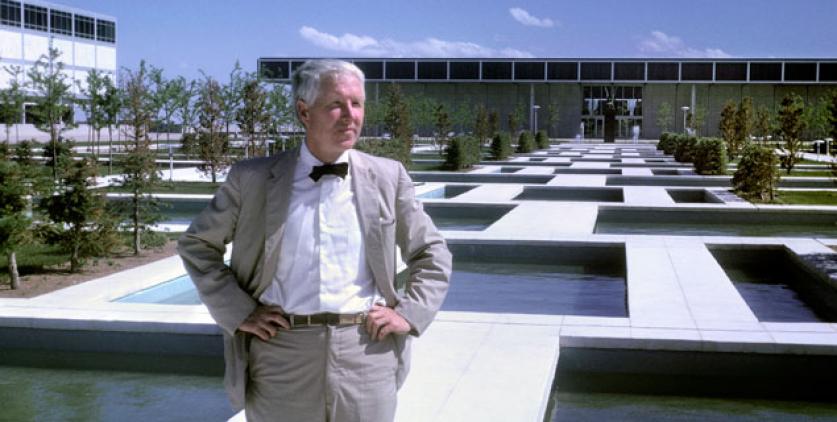

It’s pioneering Modernist landscape architect Dan Kiley in the recent motion picture Columbus.

The movie, which takes place in Columbus, Indiana, a mecca for mid-century Modernism, features many scenes in the landscapes of key Modernist sites, and we learn from the movie’s characters that Eero Saarinen is the architect at each site: the Miller House and Garden (1955); North Christian Church (1964); and, Cummins Inc. Irwin Office Building (1954, originally Irwin Union Bank and Trust). Architects for other sites, including First Christian Church (1942) by Eliel Saarinen, Columbus Regional Hospital Mental Health Center (1972) by James Polshek, and Irwin Union Bank’s Creekview Branch by Deborah Berke (2007), are also acknowledged.

However, landscape architect Dan Kiley is never once credited, though his landscapes are frequently the movie’s pivotal “supporting actors” along with the buildings for which they were seamlessly designed. Indeed, the film’s advertising includes a still image of male lead John Cho looking out onto the Miller Garden (a key dramatic moment in the film).

And, one scene shows the Miller Garden’s widely acclaimed and influential allée, where we learn that a barely visible empty plinth once held a Henry Moore sculpture that was sold at auction at Christie’s. We’re told about a sculpture we can’t see and get some ersatz product placement for Christie’s, but nothing about Kiley-designed landscape that's on screen.

Why does this matter?

Kiley is one of the nation’s most important Post War landscape architects and his influence is monumental. All three of the Kiley projects cited above, along with several other Modernist sites in Columbus, are National Historic Landmarks (NHL), an elite designation. While there are some 2,500 NHLs, only about 75 have significance in “landscape architecture” – in fact, Kiley ranks just behind Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., the father of landscape architecture, for the shear number of NHLs.

Kiley designed more than 30 landscapes in Columbus, more projects than any architect. Nationally, his significant commissions include the Art Institute of Chicago, South Garden (1962), Jefferson National Expansion Expansion Memorial, St. Louis, MO (1947, with Eero Saarinen), the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston, MA (1978, with I.M. Pei), the Donald J. Hall Sculpture Garden at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO (1988), and many others.

The Miller House and Garden, now owned by the Indianapolis Museum of Art, is acknowledged as one of the greatest Modernist collaborations. This thirteen-acre property was developed between 1953 and 1957 as a unified design through the close teamwork of Kiley, architects Eero Saarinen and Kevin Roche, interior designer Alexander Girard (who is acknowledged in the film), and clients J. Irwin and Xenia Miller. According to the NHL designation: “The Miller Garden and ‘its status as an icon of Modernism in American landscape architecture’ are the result of a fusion of ideas that cross boundaries between architecture and landscape.”

So how did Columbus become a Modernist mecca? It’s due to J. Irwin Miller. Starting in the late 1950s Miller, through his foundation, paid the design fees for new buildings (generally about 10% of a project’s total cost) provided the architect selected was one on his pre-approved list.

In a recent videotaped interview with landscape architect Joe Karr, who worked with Kiley from 1963 to 1969 on important projects including the Oakland Museum of Art in California and the Ford Foundation Atrium in New York City, it was revealed that while there were a great number of A-List architects on Miller’s pre-approved list there was only one A-List landscape architect: Dan Kiley.