The Brothers Behind Disney’s Magical Landscapes

Morgan “Bill” Evans (1910–2002) was born in Santa Monica, California. He was the youngest son of Hugh Evans, a well-known horticulturist who traveled the world in search of exotic plants for his backyard garden. Bill and his oldest brother Jack (1895–1958) grew up watching their father experiment with the flowering trees and shrubs that he successfully introduced to the Southern California climate.

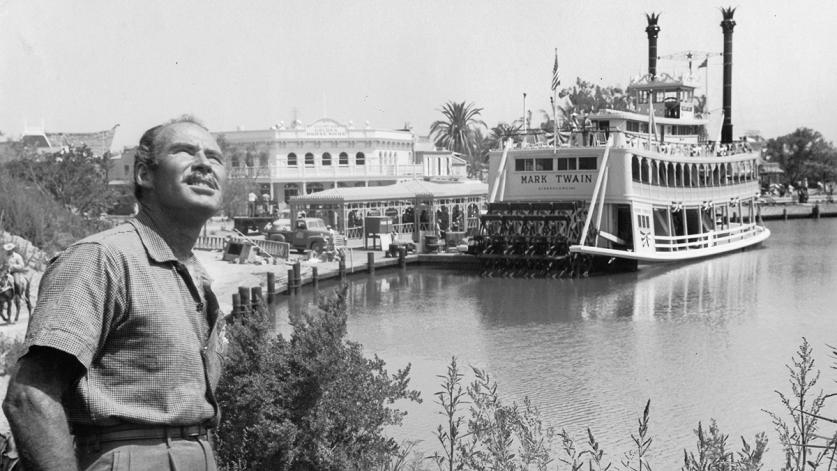

Bill Evans joined the U.S. Merchant Marine in 1928 and then studied geology at Stanford University. When the family fortune was lost in the stock market crash of 1929, he was forced to leave school a year before graduation to help his father and his brother turn a three-acre family garden into a commercial nursery. The venture was successful, and the Evanses partnered with Jack Reeves in the 1930s to establish Evans and Reeves Nursery in Brentwood, California. The nursery sold exotic plants and then expanded to offer design services. It became renowned for its unusual species and high-quality stock and supplied a clientele that included plant enthusiasts, as well as Hollywood celebrities such as Greta Garbo, Clark Gable, Elizabeth Taylor, and Walt Disney. Disney hired the Evans brothers to create a landscape design for the backyard of his Holmby Hills home, and a few years later he persuaded them to help him build a “little park” in Anaheim. The park was Disneyland.

Landscape was meant to play a leading role at Disneyland from the very beginning. Disney wanted to create accurate settings to enrich the storylines of the rides and park features, and he wanted the settings to appear to be fully developed from the outset. The Evans brothers worked with landscape architects Ruth Patricia Shellhorn and Joseph Linesch on the original design of the park. To supply their needs, the brothers scoured the state to salvage large trees from the growing network of freeways and suburban developments that was displacing acres of orchards and specimen trees amid the post-War construction boom. For Disneyland, they created an on-site nursery of trees suited to the Anaheim climate, to substitute for natural species found along the Mississippi River, New Orleans, the African jungle, or some other fictive location within the park. The imitative landscapes that the brothers created happily co-existed with their stylized planting beds of colorful annual flowers and permanent shrubs and trees, which required a great deal of manicuring, shearing, pruning, and maintenance. The brothers also transformed the site’s sandy soil into a suitable medium for supporting their plantings, and they invented a method for moving very large trees (which involved inserting a pin through the trunk) without damaging their root systems.

Visitors to Disneyland enthusiastically embraced the believable horticultural illusions, many of which were created with humorous imagination. In one case, Bill Evans extracted orange trees from groves on the original site and placed them upside down to simulate root systems along an imaginative tropical jungle riverbank. Two weeks after Disneyland opened in July 1955, Jack Evans suffered a heart attack. He died in 1958. In addition to his work at Disneyland, he played a key political role in passing legislation (enacted in 1954) requiring the licensure of landscape architects in California.

In the 1960s, Bill Evans was hired as director of landscape design to help develop the master plan for Walt Disney World in Florida, which opened in 1971. Although he formally retired from Disney in 1975, he continued to work for almost 30 years as a design and landscaping consultant with Imagineering on new features of Walt Disney World, including Disney’s Animal Kingdom, Disney-MGM Studios, Typhoon Lagoon, Magic Kingdom, and Discovery Island. With his former collaborator Joseph Linesch, he created the landscape design for EPCOT Center (1982). In addition, Evans consulted on designs for Tokyo Disneyland (1983), Disneyland Paris (1992), and Disney’s California Adventure (2001), and he contributed to the conceptual landscape design for Hong Kong Disneyland, which opened in 2005, three years after his death.

Evans’ work became associated with several major patterns of development in all the Disney parks. His planting designs created theme parks that seemed disconnected from the outside world. A continuous berm and clusters of tall trees enclosed Disneyland, while thousands of acres of managed greenbelt provided a protective buffer around Disney World. Specific plants were also used to create distinct environments within the parks, like the elm trees, for example, that lined Main Street. Other species, such as eucalyptus, linked and provided smooth transitions between different areas. To achieve his vision for Disneyland, Evans traveled widely and became connected to an international network of scientists, horticulturists, and plant specialists, and he was associated with seed banks and arboreta in numerous countries.

Evans wrote for many periodicals, including Pacific Horticulture and Sunset Magazine, and his book Disneyland: World of Flowers was published in 1965. He served on the board of trustees for the Los Angeles County Arboretum and he received awards from the American Horticultural Society and many other international organizations. In 1982, he was named a Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects, and the Landscape Architecture Foundation honored him with a Special Tribute award in 1996. Evans helped establish a template for landscape planning, design, development, and horticultural inspiration for theme parks around the world. He continued to work as a design and landscape consultant until just a few weeks before his death at the age of ninety-two.

For Further Reading:

1. Evans, Morgan. Disneyland: World of Flowers, Walt Disney Productions, Burbank, California, 1965.

2. Ghez, Didier (ed.). “Walt's People - Volume 5: Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him,” interview by Jim Korkis in Spring 1985, Xlibris, 2007.

3. Padilla, Victoria. Southern California Gardens: An Illustrated History, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1961, pp. 117–118, pp. 206–212, pp. 327–329.

4. Rollins, Bill. “While Chasing Plants Around the World, Bill Evans Changed Face of California,” Los Angeles Times, July 24, 1983.

Kelly Comras, FASLA, is principal landscape architect of KCLA in Pacific Palisades, California. She lectures and publishes on Modernist landscape architecture and is a member of the State Bar of California.