The Central Park: Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure

In The Central Park: Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure, Cynthia Brenwall presents materials from the rich collection of the New York City Municipal Archives to give new insights about the making of the city’s, and the nation’s, quintessential public park. Published in April of this year by Abrams, the copiously illustrated, hardbound volume presents and contextualizes a sizeable cache of plans, maps, elevations, hand-colored lithographs, photographs, and mechanical drawings, which together form an indispensable record of the park’s origins. Many of the images have never before been published. Including visual materials from the original, competition-winning entry submitted by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., and Calvert Vaux, the book showcases in meticulous detail the surprisingly wide range of elements and features—many built, and others that never came to fruition—that came within the park designers’ purview. Its color-filled pages of large-format maps and drawings also supply the visual evidence for an age of bold planning and unprecedented civic achievement.

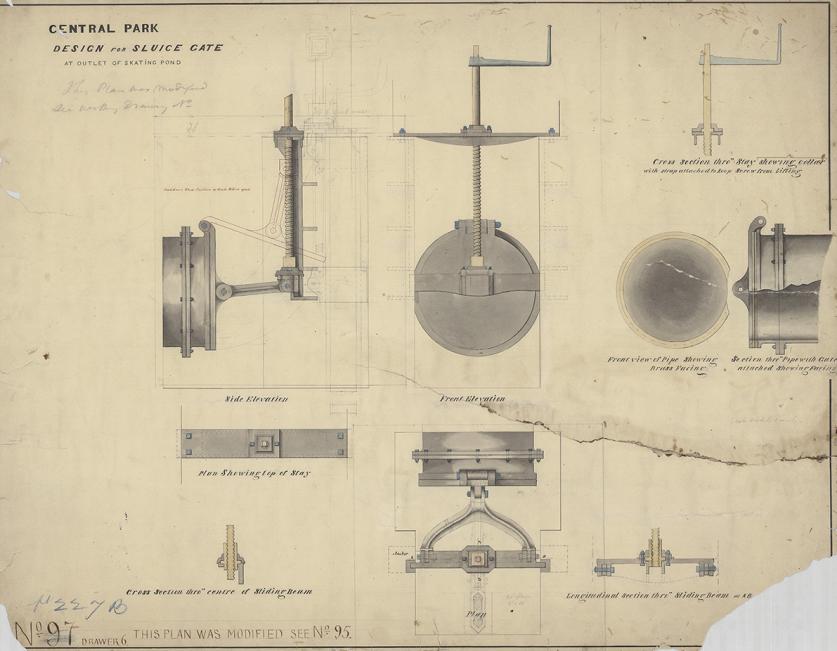

The staggering variety of arts and skills—including carpentry, plumbing, masonry, metalwork, engineering, sculpture, hydrology, botany, architecture, and landscape architecture—that were marshalled to create Central Park are represented in elegant drawings executed in painstaking detail, which themselves evince exceptional craftsmanship (even the sluice gate for the Skating Pond is beautifully and precisely rendered). What do the illustrations reveal about the relationship between the art of drawing and the art of landscape architecture?

“Staggering variety” is absolutely correct! The rendering of the sluice gate is one of my favorite drawings in the collection. That former drawing and the subsequent one made for the drainage system that was used for the transverse roads were my introduction into what I like to call, “underpinnings of the park” —those unseen and utilitarian aspects of design that evoke the sensation of being surrounded by nature in the middle of a metropolis. While many of the plans in the collection appear to be works of art by our standards, it is worth remembering that they were working drawings that passed through many hands to shape the park. The visual language that was expressed through drawing was used to communicate directly to either those engaged in the construction of the landscape and the architectural elements or others involved in approving every aspect of the plan (most notably, the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park). It is through this collaboration between planning, drawing, and construction that a sense of a unified design was achieved.

Given the wide range of visual materials available to you, how did you decide what to include in the book and what to omit?

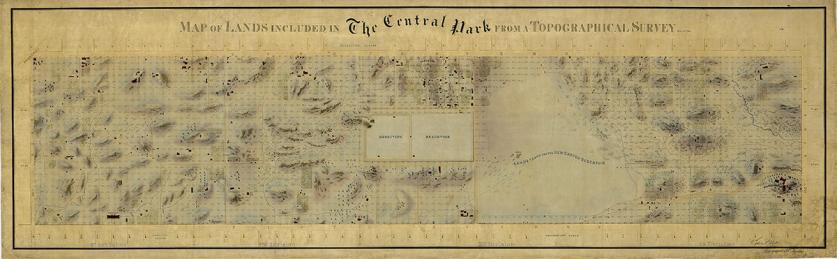

This was one of the more challenging tasks while authoring the book. With more than 1,700 drawings and plans in the collection of the NYC Municipal Archives, dating from 1856 through the mid-1930s (all of which were directly related to the construction of Central Park) there were many “must haves” that did not finally make the cut. It was, finally, a detailed map dated c. 1875 which decided the framework for the book—which was conceptualized around “a walk through the park.” This aided my decision-making on illustrative materials and narrative structure. In general, there were many cross sections of landscapes and single lines on graph paper that were easy to eliminate; although my favorite was a simple black outline of a small body of water on a single sheet of drafting cloth. An elegant sketch, although hardly any help in telling the complex story of the park.

Similarly, although I am personally partial to detail drawings featuring intricate rooflines, fireplaces and detailed decorative elements, an over-representation of such drawings would only illustrate a small section of such a monumental effort. Therefore, I had to include a broader mix, encompassing construction details, renderings, maps, architectural plans, and historic photos to effectively narrate the story of the park.

Repeatedly emerging in both the book’s imagery and in the wonderful foreword by Martin Filler is the concept of creative forethought. Do you think that the ability (and willingness) to conceive of detailed plans that would only be fully realized in the distant future was a quality particular to Olmsted, or was it characteristic of the age in which he lived?

To be honest, I think that this method of designing was not particular to Olmsted, but perhaps more characteristic of the partnership between Olmsted and Vaux. The Greensward plan outlined this vision and provided a robust framework for the realized design. For example, they were conscious of the need to have the southern section of the parkland, especially the skating lake, open to the public as soon as possible. And the sunken transverse roads were key to allowing this while construction continued smoothly. It was this manner of thoughtful planning from the onset which allowed the glorious terrace and arcade to be realized.

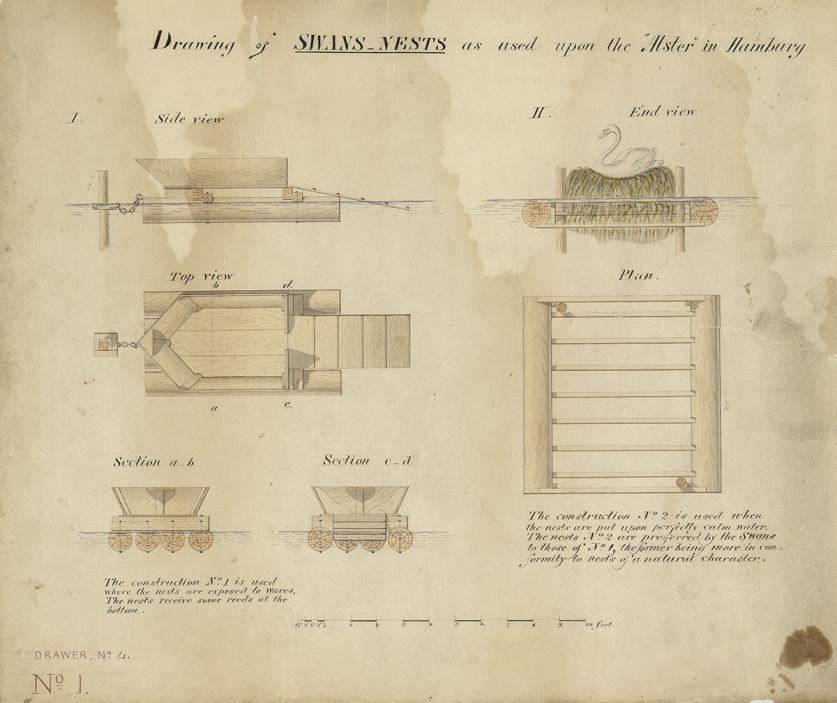

Scanning the book’s many plans and drawings reveal the prominent role of artifice in making the park, from creating a lake with pipes and hydrants to building floating swans’ nests whose designs were varied for use in rough or calm waters. What does that use of artifice say about the nineteenth-century relationship between humans and nature?

In many ways, I think that the role of artifice in mediating the interaction between people and nature is almost quintessentially nineteenth century. In an era when the promenade or evening stroll to “see and be seen” was the height of fashion, and park-goers donned their finery to attend a concert at the music pavilion, it would not seemed too outlandish to use visual devices such as a hidden grotto under a bridge to create an illusion of a history or the use of massive plantings to create the verdant Ramble in an area that was originally rocky and barren. Constructed nature was still nature and New Yorkers of the day were thrilled to have it as their own.

What do the many plans and drawings tell you about Olmsted’s and Vaux’s capacity for three-dimensional thinking?

I think that this is one of the most important aspects of their partnership. The intersection of Vaux’s work with Downing and his formal training as an architect in combination with Olmsted’s knowledge of horticulture, the park’s terrain, and his interpretation of the landscape, helped to create their shared vision of a democratic space filled with natural visual effects. This aspect is evident specifically in the presentation boards that were included in their entry for the design competition. Vaux developed before-and-after drawings of the landscape to trace the transformation of the land with water features, long vistas and elegant architectural details and highlighted the character of nature and space rather than that of the architecture. And the genius of their collaboration is embodied in this type of spatial planning.

The book introduces a wide cast of characters, including the West Point-trained civil engineer Egbert Viele, whose maps remain essential but whose hopes to design the park were dashed. What are the most interesting parts of Central Park’s history that have yet to be fully explored?

Obviously, there has been a LOT written about Central Park, but I believe that there is still much to know. For instance, the history of the land before it was taken by eminent domain. During my research, I found a small map dated 1856 in our collection that shows that there was a small Jewish cemetery among the buildings at Mount Saint Vincent in the north of the park. Who were the interred and what happened to those who were buried there?

I am also fascinated by how much can be learned about a broader history of New York City and the late 1900s through the lens of the park’s creation. An egalitarian public space that was planned for all New Yorkers to benefit from access to nature, it is rich with the untold stories of men (and yes, they were all men) who planned, designed and built the park. Furthermore, the amenities provided for city dwellers, including areas for culture and music, access to clean drinking water and venues for “healthful recreation” such as lawn tennis courts and ice skating and quiet contemplation—this gives reason to explore Vaux and Olmsted’s views on urban planning and their convictions on the role of civic space.

How did your training as a conservator influence the content of the book?

My training as both a conservator and an art historian have taught me to decipher the fine details in a drawing that aid in telling a visual story. Seeing the hand of the maker in each drawing and its role in communicating with builders during construction was essential. Further, critical thinking is also an important aspect of my background. This was invaluable while drafting the book, as conservators test materials and techniques rather than rely on assumptions before undertaking the treatment of a document. And this was my approach to annual reports, photographs and documentation related to the park, I detached myself from my own mooring in the twenty-first century and dispassionately interpreted supporting material to confirm details.

In your research for the book, what surprised you most about Central Park and/or its makers?

Honestly, there were so many little things that make the story of the park so rich and interesting. But most notably, three things kept coming up as I worked on the text for the book. Firstly, it was astonishing that Calvert Vaux predicted his place in history very early into his partnership with Frederick Law Olmsted. While Vaux was a well-trained architect, a partner in Alexander Jackson Downing’s influential landscape design firm in Newburgh, NY as well as the one who initiated the partnership with Olmsted to enter the design competition for the park, he is all but forgotten today by the general public. Only days after work began on the park, Olmsted was named architect-in-chief and superintendent of the project and given a non-voting seat on the board of Commissioners, while Vaux was referred to as “the superintendent’s associate in design No. 33” in the minutes of the Board of Commissioners. And he had to be hired by Olmsted as one of his assistants with a daily wage rather than a yearly salary despite being the one entrusted with the elegant architectural design and planning of the park.

Secondly, I found the plans for the drainage and water systems incredible. The park could not have been built without having proper drainage installed; a fact that Viele pointed out to the Board in 1856 when he warned that if the land was not properly drained, it would remain, “a pestilential spot, where rank vegetation and miasmic odors taint every breath of air.” Many of these components are drawings that are fully colored renderings of pipes, stone fill and basins that were used to drain the land as well harness water from the Croton Aqueduct to create man-made bodies of water, fill the ornamental fountains and provide drinking water throughout the park.

Do you have any plans for other books or projects?

I’m in the early stages of researching and brainstorming for my next project. Writing this book has been such an opportunity to delve into the social history of the city through the lens of civic art, design and architecture that I am hoping that I will be able to further explore this aspect.

Cynthia S. Brenwall is a conservator at the New York City Municipal Archives, which preserves the historical records of the government of New York City. A graduate of the Pratt Institute and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, she has previously worked in the Smithsonian Institution as an archivist.