Is Chicago About to Ruin Jackson Park?

If you’re looking for a good example of poorly integrated site planning, look at what Chicago is and isn’t doing at historic Jackson Park. The city has already lopped off more than 20 acres of the park for the Obama Presidential Center (OPC), there’s a proposal to consolidate (and privatize) two golf courses, and road closures and re-alignments are also being planned, along with other changes.

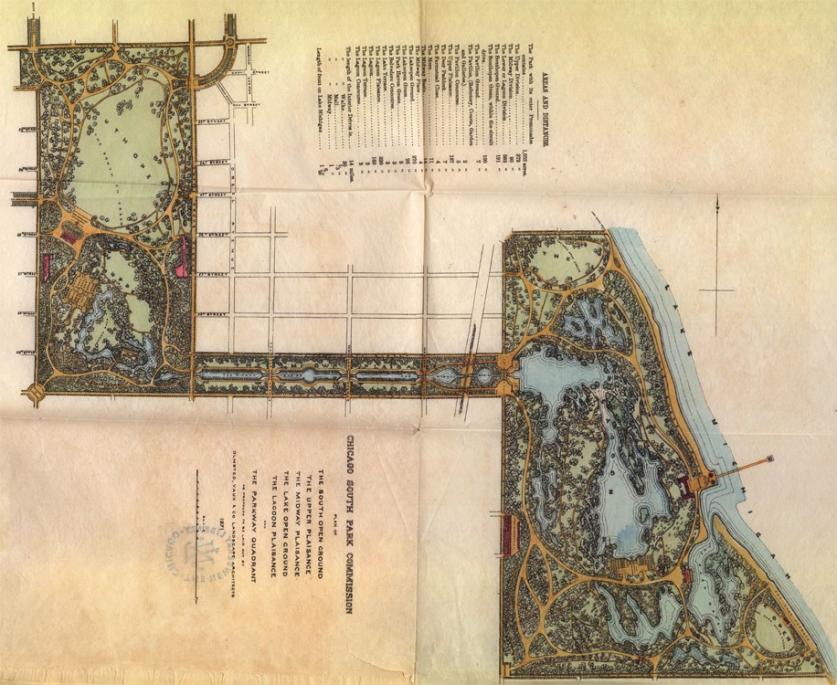

This isn’t just any public open space; this is historic parkland originally designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., and Calvert Vaux (of New York’s Central Park fame). In fact, Jackson Park, the Midway Plaisance, and Washington Park – the South Park System – together comprise the only Olmsted & Vaux-designed park system outside of New York State. Moreover, all three parks are listed in the National Register of Historic Places – Jackson and the Midway in 1972, and Washington in 2004.

The OPC, originally sold to the public as a presidential library to be administered by the National Archives, a federal entity, will instead be a private facility occupying confiscated public parkland. And now the OPC’s proponents want more public parkland, up to five acres of the neighboring Midway Plaisance, for an above-ground parking garage.

So how could this happen? [a] There’s no overarching comprehensive plan or vision for Jackson Park (not to mention the South Park System as a whole); and [b], the public review processes involved are complicated, which gives cover to the City of Chicago, OPC proponents, golf course consolidation proponents, and others. Consequently, all of the proposed projects are being looked at in isolation rather than as interdependent. To understand why that’s a problem, a quick historic overview is necessary.

Olmsted and Vaux designed the park system in 1871 on flat land Olmsted deemed “extremely bleak.” The site’s characteristic level topography was ultimately leveraged in the park’s design to provide sweeping views to what Olmsted considered the park’s most important attribute, Lake Michigan. Some two decades later, Jackson Park was chosen for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Olmsted, working with his associate Henry Codman and architects Daniel Burnham and John Welborn Root, designed the setting of the vaunted White City, a showcase of Beaux-Arts classicism whose formality was artfully juxtaposed with the rugged shorelines of naturalistic lagoons and islands. It was a massive success; nearly four-dozen nations were represented at the exposition and it attracted more than 25 million people (for context, the U.S. population was then approximately 63 million).

After the exposition closed, a series of fires ravaged the site, beginning in January 1894, leaving a landscape strewn with charred remains. After the remaining crippled structures were demolished, only five exhibition buildings were left standing. In 1895, Olmsted turned his attention to the site for a third time, resulting in a comprehensive plan that would heal Jackson Park. He and his firm, Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot, proposed that “many of the features characteristic of the landscape design of the World's Fair” would be retained while providing “all of the recreative facilities which the modern park should include for refined and enlightened recreation and exercise." The 1895 plan occupies a special place in the history of landscape architectureas perhaps the nation's earliest large-scale brownfield-remediation project.

During the twentieth century, particularly from the post-War years to the 1980s, deferred maintenance and a lack of comprehensive planning led to the park’s decline. Instead there were piecemeal projects, such as the widening of Cornell Drive and other intriguing chapters, notably the installation of a NIKE missile site in the park’s lawn tennis area, 1956-71.

Importantly, in 1972, just six years after the creation of the National Register of Historic Places, Jackson Park and the Midway Plaisance were listed in the Register. However, the National Register’s 1972 statement of significance, a single typewritten page, needs to be updated to more completely reflect the totality of the park’s unique and unrivaled history (for context, the 2004 National Register designation for Washington Park is 61 pages in length). In 1995 the Chicago Park District (CPD) began the process for such an update, but it is unclear why the resulting 21-page historical assessment, found buried in the appendix to a 2013 study, was never advanced.

Similar such research also underpins other important planning efforts over the past two decades and all of it should be daylit to inform the current reviews of the OPC. For example, during the city’s park renaissance under Mayor Richard M. Daley (who served five terms, 1989-2011), the CPD authorized the South Lakefront Framework Plan, which covered Jackson and Washington Parks and the South Shore Cultural Center. Undertaken in 1999, this comprehensive and holistic plan to renew the park was the first in more than a century. According to CPD’s website: “The framework plan’s purpose was to define the changing needs of these parks, to provide a plan to enhance each of the park’s commitments to serving the neighboring communities and to preserve the intended historic character.”

The 1999 Plan has laudatory “overall objectives” and “guiding principles,” but most importantly, it identifies historic context as the key to managing change at Jackson Park:

Historic Context is an important consideration as one looks at upgrading present conditions and weighing future improvements. The original Olmsted design has served the park well over time and should not be compromised by future plans (emphasis added).

The 1999 Plan was never completed, though its website was amended to reflect the city’s position that the OPC is an inevitable addition.

Separately, after commissioning a study by the Army Corps of Engineers, the CPD entered into an ambitious and innovative partnership with the not-for-profit Project 120, which embarked on a “historically based and integrated project of preservation and habitat restoration” in Jackson Park. After Jackson Park was selected as the site for the OPC, the multi-million-dollar federal-and-state-funded Project 120 went dormant in October 2016.

The OPC is currently the subject of reviews under the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) and the National Historic Preservation Act, specifically Section 106 of the latter. The Section 106 compliance review will identify and assess the adverse effects posed by the OPC, and it rely on The Secretary of the Interior’s Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes in that assessment. The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) is an official consulting party to the Section 106 process and has submitted a detailed examination of the proposals for Jackson Park (which can be downloaded here), including the 21-page updated history for the park, as previously noted.

Finally, the OPC’s proponents claim the project respects Olmsted’s original vision. That’s not true, and we know that because Olmsted said so. The 1895 plan to heal the park included treatment of the landscape surrounding the Museum of Science and Industry to highlight that building’s architecture. Here, Olmsted was unmistakably explicit, stating that the Museum was meant to be the only “dominating object of interest” in the park:

All other buildings and structures to be within the park boundaries are to be placed and planned exclusively with a view to advancing the ruling purpose of the park. They are to be auxiliary to and subordinate to the scenery of the park (emphasis added).

–Olmsted letter to South Park Board president Joseph Donnersberger, May 7, 1894

Less than a decade after Olmsted’s death, Chicago began to take shape around another plan that eventually achieved a kind of legendary status. Daniel Burnham’s famous 1909 Plan of Chicago has been called “one of the most noted documents in the history of city planning.” That makes it all the more remarkable—and truly sad—that so much of what Frederick Law Olmsted achieved in Chicago might now be lost because of a lack of value for historic context and comprehensive planning—and all while invoking his name.

This article originally appeared on the Huffington Post on January 3, 2018.