Civil Rights Landmark in Austin, Texas, Could Be Erased

Known affectionately as “Muny,” Lions Municipal Golf Course was constructed in 1924 just two miles west of the State Capitol in Austin, Texas. Aside from its historic design, Muny is best known as the first desegregated municipal golf course in the South, thanks to the rebellious act of a young African American caddie. The University of Texas, Austin, which owns the land that Muny occupies and leases it to the City of Austin, decided in 2011 that it will not renew the lease beyond 2019, opting instead to destroy Muny to make way for a mixed-use development.

HISTORY

Lions Municipal Golf Course is an eighteen-hole public golf course situated on approximately 141 acres in Austin, Texas. The first public course to open in Austin, Muny was constructed in 1924-1925 by the Austin Lions Club, which arranged to lease a portion of the parcel (known as the Brackenridge Tract) given to the University of Texas in 1910 by benefactor George W. Brackenridge. The Lions Club raised funds for the construction of both the course and the clubhouse, with club member B.F. Rowe designing the former and local architect Edwin Kreisle designing the latter, which was added in 1930. In 1936 the operation of the course was transferred to the City of Austin. That same year, renowned golf architect Albert Tillinghast redesigned several holes.

Shortly after the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Sweatt v. Painter desegregated the University of Texas Law School in 1950, Muny became the first municipal golf course in the Old Confederacy, and one of the first southern public accommodations, to desegregate non-violently and without court order. In the latter half of 1950, Alvin Propps, a nine-year-old African American caddie at Muny, along with another African American youth, was detained for playing the course in defiance of Jim Crow laws. Taylor Glass, the Mayor of Austin at that time, quickly conferred with members of the city council, and a decision was made not to prosecute Propps or his companion. From that point forward, African Americans played golf at Muny.

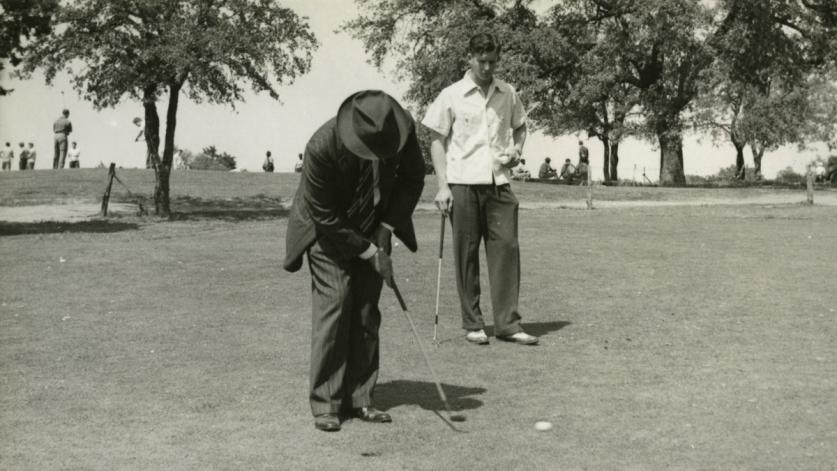

Shortly after Muny was desegregated, heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, who publicly opposed Jim Crow laws and became an ambassador to the game of golf after his retirement from boxing, played the course (he would return to play the course again in July 1953). Later, in 1951, Austin desegregated its public library, and a fire station on Lydia Street in Austin was integrated in 1952. Notably, all of this occurred well before the groundbreaking 1954 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education, which mandated that schools and other public facilities be racially integrated.

Although Muny is a site that represents an important advance in the history of U.S. civil rights, it has not always been recognized as such. In 1972 the University of Texas announced plans to convert the property to serve other purposes, prompting the creation of the “Save Muny” campaign, which eventually succeeded in saving the golf course. Partially redesigned in 1976, the course was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2016. Today Muny is the most frequently played municipal golf course in Austin, and, in addition to its historical significance, serves as a welcoming, open green space in the urban environment.

THREAT

In February 2011, the University of Texas Board of Regents decided not to renew the City’s lease of Muny beyond May 25, 2019, in order to advance a plan to develop a mixed-use complex (with potentially up to 18,000 tenants for the entire Brackenridge Tract) on the site. After the redevelopment plan met with considerable public outcry, longtime Austin resident and well-known professional golfer Ben Crenshaw unveiled a plan in February 2017 to restore the course to its 1950s-era layout, lending his expertise in golf-course architecture to the endeavor, as well as crucial support in securing private donations.

The Texas Senate also passed a bill in 2017 that recognized Muny’s historical significance and provided for the transfer of Muny to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department to preserve it as a heritage site and golf course. Although the bill did not pass the Texas House (dying in committee), the university and the City of Austin, in coordination with Texas legislators, have entered negotiations on Muny’s future in preparation for the 2019 legislative session. Under the current lease, the university earns close to $500,000 but claims the land could yield up to $5.5 million annually in rent if fully developed. Very recently the university offered to extend the lease to the city past the 2019 deadline, conditioned on a sizeable increase in the rental-fee agreement. It is unclear where the negotiations stand between the university and city at present.

In the past the University has advanced the idea of preserving just the clubhouse and not the course itself. However, the clubhouse was the last part of the Muny site to desegregate, with city officials even building a separate clubhouse (no longer standing) for African Americans after the course was open to them. Prominent leaders of Austin’s African American community, including Pastor Joseph Parker of the David Chapel Missionary Baptist Church and Nelson Linder, head of the local NAACP branch, have pushed back publicly against that idea.

Many historians, advocates, and congressional leaders have noted Muny’s historical significance. Glenda Gilmore, the Peter V. and C. Vann Woodward Professor of History at Yale University, succinctly stated the national importance of Muny's desegregation: “Historians searching for the impetus of the 'classical phase of the Civil Rights Movement,' preceding Brown v. Board in 1954 and the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, have posited a 'long civil rights movement' that preceded those iconic struggles. In other words, Lions Municipal Golf Course is representative of the 'birth of the civil rights movement.'” Jacqueline Jones, chair of the UT Austin Department of History, has called Muny “an asset of immense historical and educational value,” adding that it “is as much a piece of the American story—and potentially as powerful as a teachable experience—as the historic battlefields we protect and embrace.” Members of the U.S. Congressional Black Caucus have also added their voices in support of Muny, and resolutions acknowledging the site’s history have been passed by the Texas House of Representatives, the City of Austin, and Travis County, Texas.

WHAT YOU CAN DO TO HELP

The volunteer group Save Muny remains at the forefront of the efforts to preserve and protect this historic civil rights landmark. Interested persons are encouraged to support the work of the organization and add their name to a petition to be presented to the University of Texas Board of Regents and the Austin City Council.