Conrad Wirth Biography

Conrad Louis Wirth was born in 1899. His father, Theodore Wirth, was the superintendent of the Hartford, Connecticut, park system. The family moved in 1906 when the elder Wirth took the position of superintendent of Minneapolis parks.

As an adolescent, Wirth attended military school in Wisconsin. He went on to study landscape architecture with Frank A. Waugh at the Massachusetts Agricultural College (later the University of Massachusetts, Amherst), graduating with a B.S.L.A. in 1923. Wirth moved to San Francisco, where he apprenticed with nurseryman Donald McLaren. After two years he moved to New Orleans and started his own landscape architecture firm with a partner. Initially successful, the development boom soon turned to bust and by 1927 he was out of business. In 1928, he relocated again, this time to Washington, D.C., where Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., secured a job for him with the National Capital Park and Planning Commission. In 1931 Park Service director Horace M. Albright offered him a transfer to the National Park Service (NPS), where Wirth became assistant director in charge of the Branch of Lands. Known as Connie by many of his colleagues, he remained in the NPS’s Washington Office for the next 33 years, running the agency from 1951 until 1964, the longest tenure of any director before or since.

A transformation of the NPS began in the spring of 1933, when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt mobilized the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). In his position as chief land planner, Wirth investigated possible additions to the park system for the previous two years. With the CCC, he now became the principal liaison to dozens of state governments, many of which had virtually no state parks, but which were rapidly acquiring land in order to take advantage of the federal government’s offer to develop them with CCC labor and funds. Wirth oversaw and reviewed all planning, design, and construction undertaken by the NPS-CCC state park program. In 1936 the NPS consolidated its CCC programs, bringing together the state park program and national park CCC camps under Wirth’s leadership. By 1941 more than 560 state, county, and municipal parks had been created or redeveloped by Wirth’s program, in partnership with 140 state and local park agencies.

World War II put an end to the CCC and other New Deal programs, but the projects had been a great success. After the war visitors inundated state and national parks, and often traffic jams, long lines outside bathrooms, overflowing parking lots, and no available accommodations. Superintendents could not adequately protect their parks, much less staff their museums and interpretive programs. Many park concessionaires struggled to reopen aging and inadequate facilities.

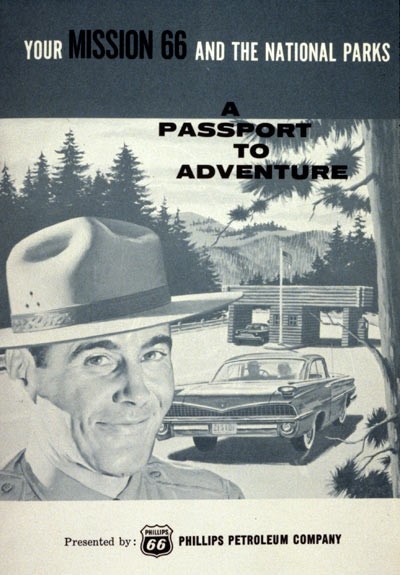

In the face of these challenges, Wirth became NPS director near the end of 1951. As recession threatened, President Dwight D. Eisenhower looked favorably on public works spending that would stimulate the economy. After eight months of planning Wirth and his staff outlined the scope of Mission 66, a ten-year program to improve, modernize, and expand the national park system in time for the fiftieth anniversary of the NPS in 1966.

By 1966 lawmakers had spent about $1 billion on the Mission 66 program. The NPS constructed or reconstructed thousands of miles of roads and hundreds of miles of trails, and built hundreds of buildings, including more than 100 visitor centers. NPS Staff were expanded and professionalized through newly established training centers.

Mission 66 forged a new identity for the park system, intended to meet the recreational and social needs of postwar American society. Improvements were characterized by a new idiom of Modernist park architecture exemplified in its use of steel, concrete, prefabricated elements, unusual fenestration, climate control, and contemporary architecture and planning ideas.

Greeted at first with enthusiasm, Mission 66 was also criticized. Opponents complained that it emphasized construction as a one-dimensional solution to the complex social and environmental problems park managers were facing, and that it abandoned the Rustic style of park architecture and landscape design. The program soon led the NPS into bitter controversy as the postwar environmental movement began to take shape and exert its strength. Mission 66 hastened the advent of environmentalism by creating concern that the NPS was overdeveloping parks while failing to take other steps to preserve wilderness. Wirth stepped down as NPS director at the beginning of 1964, two years before his program was to have been completed. The creation of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation in 1962 and the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964 signaled the advent of what Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall described as New Conservation. Many park acquisitions and expansions completed over the next decade, however, had their roots in Mission 66 proposals.

Wirth published many articles and speeches in his lifetime. He was elected president of the American Institute of Park Executives, was a trustee of the National Geographic Society and a consultant to the American Conservation Association. His awards included the Department of the Interior’s Distinguished Service Award, the American Forestry Association’s Conservation Award, the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society’s Pugsley Gold Medal, and several honorary doctorates. In 1972 the American Society of Landscape Architects gave him its highest honor, the ASLA Medal. His 1980 memoir, Parks, Politics, and the People, describes his professional activities in detail. Wirth died in 1993 and was buried at Lakewood Memorial Cemetery in Minneapolis.