Consulting Parties Find Serious Flaws in OPC Documents

Official consulting parties to the Section 106 and NEPA reviews currently underway for the Obama Presidential Center have responded to a series of recently released reports meant to guide the review process: The Section 106 Historic Properties Identification Report (HPI), dated March 15, 2018; a Draft Section 106 Archaeological Properties Identification Report (APIR), dated February 2018; and a Draft Purpose and Need Statement of the OPC Mobility Improvements to Support the South Lakefront Framework Plan, dated February 6, 2018. Following a public meeting on March 29, 2018, consulting parties had until April 19, 2018, to submit official comments on the documents, and those submissions have raised many fundamental questions.

Multiple groups discussed the inconsistency in the reports regarding the very definition of the project under review. Jackson Park Watch, for example, highlighted the confusion arising from “misleading references to and uses of the South Lakefront Framework Plan update,” an issue that was expanded on by the group Friends of the Parks:

The executive summaries and the reports (one still in draft form) to this process seem to have inconsistent and inarticulate concepts about what is being reported on and reviewed and for what purpose. The references to the South Lakefront Framework Plan are particularly inapposite since that plan is not now at a stage where it can be assessed…the plan even in its current configuration did not exist in a way that would enable the two major reports currently under discussion in these Section 106 processes to have considered it. The CPD Board of Commissioners did not take a vote to approve the SLFP. The In short, the SLFP could never have been part of the plans that are at the center of this review process since it did not exist; and may not exist in reviewable form for decades.

Friends of the Parks also commented on the period of significance that the HPI established for Jackson Park, 1871-1953, calling the dates “inappropriately and arbitrarily limited” and noting that “Major and critical alterations to Jackson Park and its roadways, trails and lakefront have been implemented since 1953 that surely need to be respected and protected.” Landmarks Illinois specifically requested that the period of significance be extended to 1968, asserting:

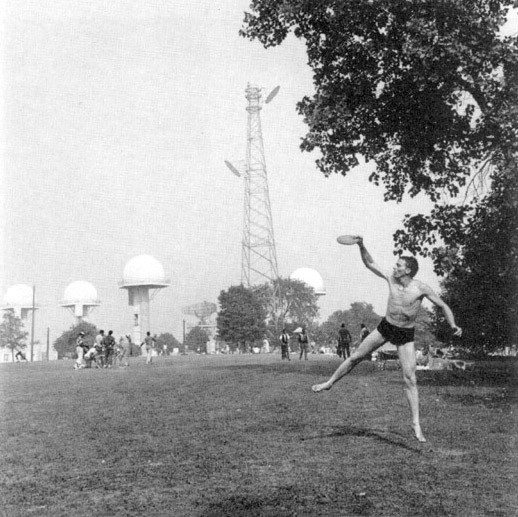

Ending the period of significance at 1953 denies the opportunity for any properties built between 1953 and 1968 to be considered for National Register designation, or events of social significance to be acknowledged, despite qualifying for consideration based on the 50-year rule…There is precedent in past successful National Register nominations within the Chicago Park District to extend the period of significance to 50 years prior to the nomination date. This is the case with Washington Park and most of the major parks within the system.

Extending the period of significance to 1968 would also recognize the changes that came to Jackson Park in the wake of the federally mandated NIKE missile base that was installed there in the mid-1950s and that represents an important aspect of U.S. social history at the height of the Cold War. And indeed, as The Cultural Landscape Foundation’s (TCLF) response to the reports made clear, the APIR, which assessed archaeological finds under Criterion D alone, must also be expanded to account for additional National Register criteria in accord with guidance from the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation:

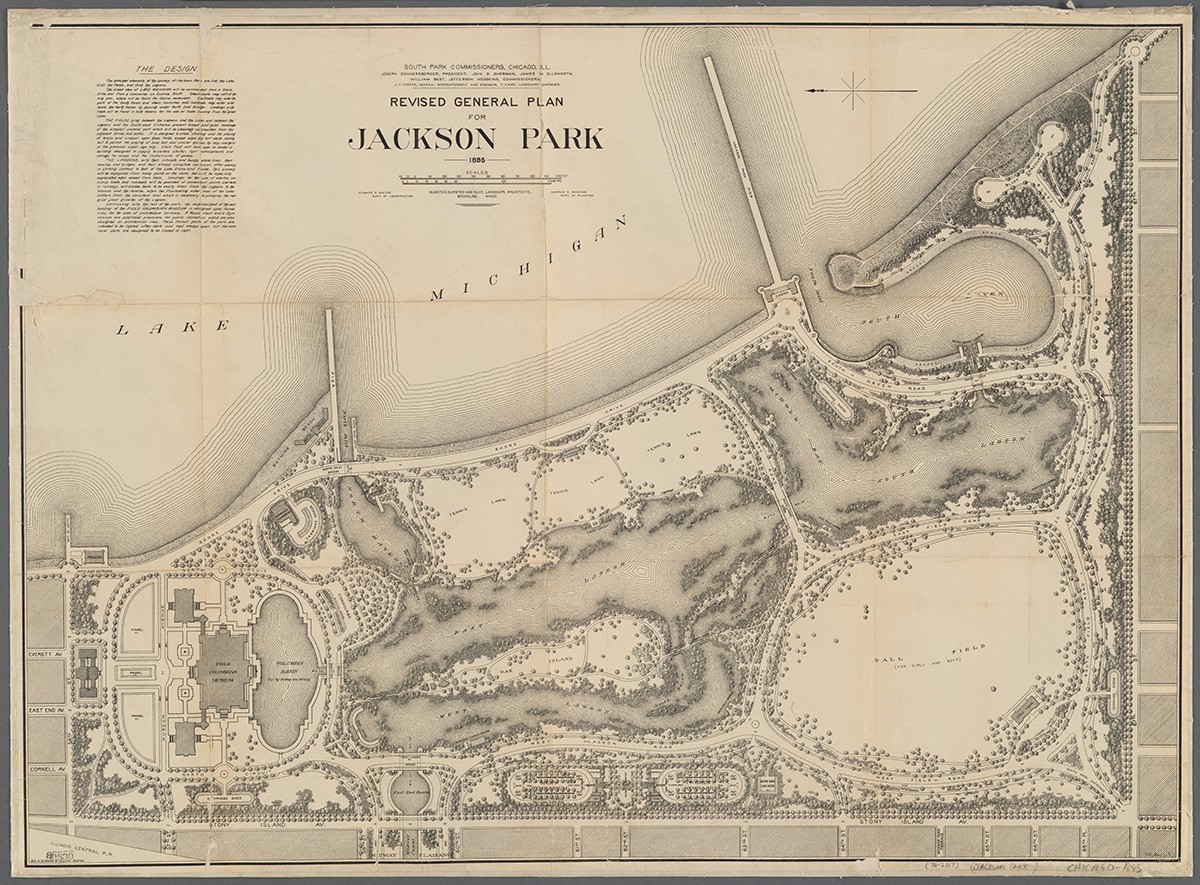

[The HPI] explicitly emphasizes the park’s key role in the broader historical movement of reform-era recreational planning: “One of the most significant aspects of the 1895 Plan was that it included one of the Olmsted firm’s first open-air gymnasiums (an amenity that would soon influence park development throughout the nation)” (p. 67, emphasis added). The HPI also makes abundantly clear that Jackson Park was the site of the World’s Columbian Exposition, whose influence in shaping the cultural life of the nation is very well known. Likewise, there can be little doubt of the renown of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., whom the HPI says is “recognized today as the ‘Father of American Landscape Architecture’” (p. 5)…In other words, the HPI itself makes a strong case that the archaeological evaluation for Jackson Park should also have been carried out under Criteria A and C as a site “associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our history” (Criterion A) and that “represents the work of a master” (Criterion C). Until the archaeological materials are fully evaluated under the additional criteria, the APIR must be regarded as incomplete and, therefore, unready for further substantive review or comment.

TCLF also noted the lack of any significant discussion about the park’s generally flat topography and the various panoramic views to Lake Michigan in the HPI’s analysis of Jackson Park’s historical integrity. That theme was also addressed in a response by the National Association for Olmsted Parks, a noted authority on the Olmsted legacy:

…given the generally flat topography of the site and the very deliberate choreography of articulated sight-lines and interrelationships intended by the Olmsted firm planning, it is clear that any structural additions to this heritage park should give critical attention to protecting the original design intent. In particular, this includes not obstructing planned views within and without the park, nor creating destructive shadow patterns which will affect both vegetative health and the intended artistry of diverse vistas.

And while the HPI reports that Jackson Park “generally retains a high level of integrity” (p. 60), the integrity of the western perimeter (where the OPC is slated to be built) is surprisingly assessed as being categorically low. To back that claim, the HPI sites “the impact of roadway projects and loss of plantings throughout the area” (p. 75). But as TCLF points out, “…by that logic, the southern perimeter, northern perimeter, eastern beachfront, West Lagoon, Wooded Island, and other areas of the park must also be regarded as having low historical integrity because they are in equal proximity to roads that have been widened and are areas that have also experienced a loss of plantings.” The HPI does indeed take great pains to establish that Jackson Park’s historical integrity is intact despite its roadways. But that is very much at odds with the opinion of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency as expressed in an official letter dated December 10, 2012. In that letter, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Anne E. Haaker wrote that Jackson Park’s roadway configuration is a defining characteristic of the park’s 1905 plan that must be respected:

As currently designed, [Jackson Park] retains a great deal of its integrity. While some of the original features have been modified, or removed, the remaining defining characteristics such as the overall plan developed by Olmstead, Olmstead, and Elliot as depicted on the 1905 map must be respected. These include, but are not limited to, the Golden Lady statue, the Osaka Garden, the current roadway configuration, the beach house, and the configuration of the lagoons (emphasis added).

The group Save the Midway! rightly pointed out that because the full extent of the Midway Plaisance has now been added to the area of potential effects, a full analysis of its historical integrity should be added to the HPI. The group also observed that, as currently planned, the OPC would absorb and significantly alter the Women’s Perennial Garden, located on the original site of the Women’s Pavilion of the 1893 World’s Fair. That pavilion was designed by Sophia Hayden, who was the first woman to graduate from the architecture program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the current landscape that marks the site was designed by noted woman landscape designer May E. McAdam.

Still other issues revolved around the Purpose and Need Statement, which introduces the University of Chicago’s proposal to locate the OPC on Chicago’s South Side and directs the reader to a certain Exhibit 1b. But Exhibit 1b is a map of Jackson Park, not the University of Chicago proposal. Given that the proposal is thus introduced as a supporting document for the Purpose and Need Statement, which is itself a foundational element of the Section 106 review, it is very unusual that the proposal was not included as an addendum to the statement. As TCLF indicated in its remarks, “[the] absence [of the proposal] impedes the fullest possible understanding of both the purpose of and need for the actions now under consideration. We therefore request that a copy of the University of Chicago proposal be made available to all consulting parties immediately.”

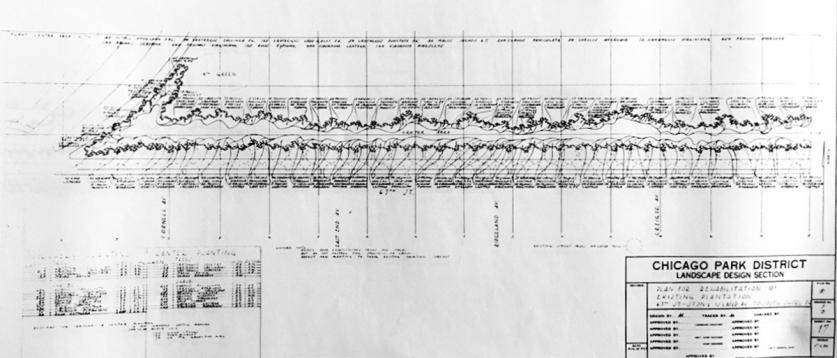

Preservation Chicago reiterated the importance of Jackson Park and its historic features, including the many archaeological remains that will surely be destroyed if the OPC is built. The group also noted the potential loss of the landscape designed by Alfred Caldwell along the park’s western perimeter, which comprises plantings “added in the 1930s and meant to shelter the park and its visitors from the noise, traffic and bustle of busy Stony Island Avenue, and to create a calming and restful park experience.” Caldwell’s recently rediscovered planting plans (thanks to the work of Preservation Chicago) add another important layer to the park’s already rich design history.

Finally, it is notable that issues raised by consulting parties in these formal responses have been raised before, and several questions submitted by TCLF to the City of Chicago during a public meeting on March 29, 2018, have not been answered to date, despite assurances that answers would be forthcoming “within the next week.” Transparency and responsiveness are critical to the Section 106 review process, which, by its nature, is complex and collaborative. The surest way to invalidate the process is to treat the outcome as a foregone conclusion.