Dan Kiley Past and Present

Vermont was at its finest. The sky was blue, pastures were green, and bright sunlight streamed through a grove of beech trees.

As we drove down the gravel back roads from Burlington to Charlotte, I was reminded of my first trip down these roads some 17 years previous, also in the month of June, to interview for a job with an eccentric, long white-haired man. I was fortunate enough to be hired, and worked with Dan Kiley for two years. Now I was returning to the familiar setting, only this time it was I who would be doing the interviewing along with Charles Birnbaum and videographer, Jim Sheldon.

When we arrived at Dan's house in East Charlotte everything was much as I remembered: the small court created by outbuildings with tin roofs sheltered Dan's old white Morgan car and other farm equipment. The narrow boardwalk hovering above the ground marked a path through the woods to the house where we were greeted by the eighty-nine-year-old Kiley. Dan was thinner but retained his characteristic hair and slightly rumpled attire. His wry wit was also in good form, as he teased Charles about not really being who he said he was. After greeting us, he signed our copies of his self-titled book, Dan Kiley: The complete works of America's Master Landscape Architect and then we walked along the boardwalk in order to sit and talk under the shade of a pavilion. Our view looked out to a small grove of birch trees and a ground plane covered with ferns that Dan had planted years ago. As I began to ask Dan questions about his early work with the architect Eero Saarinen on the Irwin Miller Garden, I realized how much this one man's life has influenced the profession of landscape architecture and my own career. When I arrived in Vermont from Cambridge, Massachusetts, I was not completely prepared for the office setting I found there. I am not sure what I thought Dan's office would be like (maybe a minimalist, white box), but I was taken aback by the rural if not rustic qualities of Dan's office and house. During my stay the office was located in what was an old carriage-house located about an eighth of a mile beyond Dan's house. Wood burning stoves provided heat for the office and after lunch a few of us would go cross-country skiing.

Dan has since moved the office into the basement of his house. His living environment contrasts with the precisely gridded plantings and minimalist use of plants in his design work and at the same time reflects his definition of landscape architecture as "a walk in nature." But beyond the formal aspects of applying modernist principles to garden design, Dan's life is as much about living life on his own terms. Moving to Vermont was not about developing a "landscape architecture business," but to pursue what he called "good skiing."

Throughout our two-day visit to Vermont, I reflected upon the valuable experience that I gained working directly with Dan. I was fortunate to work on many amazing projects throughout the country. I remember riding in the backseat of a car with Dan enroute to Collegeville, Minnesota, for a meeting at St. John's University, when Dan saw me flipping through my sketchbook. He pulled the book away from me, scanned his eyes over my primitive drawings, closed the book and said, "get the diagram right first," a phrase that I have never forgotten.

Much of my design work was transformed by living in Vermont and working with Dan. The most obvious development being an understanding of how plants structure space. I also came to understand that formal strategies will only carry you so far toward becoming a good designer. It is just as important, if not more so, that you understand who you are as a person so that you can approach your work with passion and boldness. Dan is such a person.

As the interview ended and we shared a glass of wine, I rediscovered Dan's gridded minimalist plantings as an abstraction of his own living environment. Dan seeks the simple but not the simplistic solution. His mastery of the grid as an organizational device and his thoughtful selection of plants work together to form a dynamic spatial sequence that is as rich as a walk in nature.

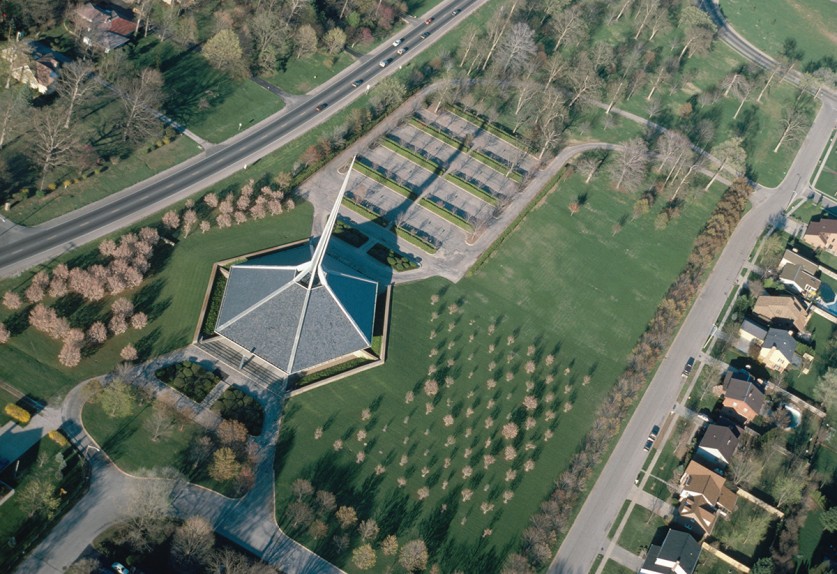

On the drive back to Boston, I thought about the importance of Dan's career and the need to preserve his projects for future generations to see. The work of TCLF to document Kiley and Saarinen's Columbus, Indiana projects is critical to give young people an understanding of landscape architecture and design. Finally, I smiled when I opened my signed Dan Kiley book, and read what he had written, which I believe summarizes his approach to life and landscape architecture: "I wish we could replicate the past but I think it against nature."