Dimensions of Dan Kiley, Part 2

By Chris Dunn

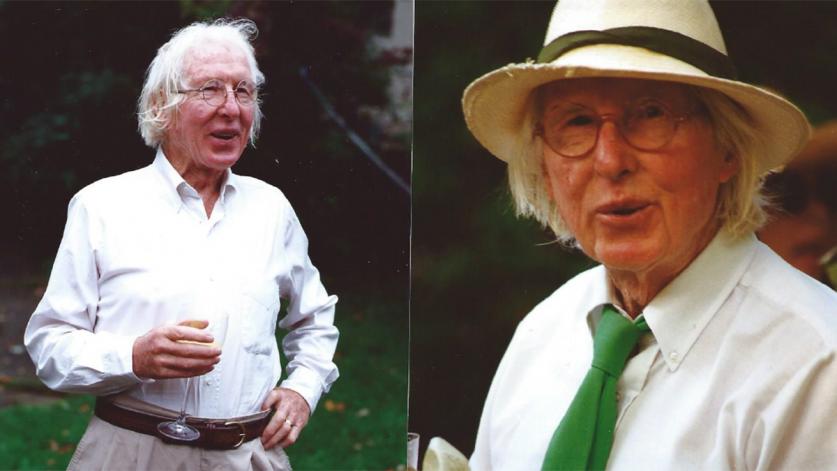

Editor's note: In this second installment in a two-part series, landscape architect Chris Dunn shares insights from his personal and professional relationships with Dan Kiley, which spanned a quarter century. Dunn was Kiley’s protégé and son-in-law. Part 1 of the series can be found here.

Having already written about how I came to know Dan Kiley, and about his design philosophy and the influences behind it, I want to begin this second segment by exploring some points that I hope will shed more light on particular aspects of his built work.

Although Dan’s work is obviously and necessarily informed by a deep knowledge of landscape design and horticulture, a less-explored aspect of his practice was his innate understanding and use of architectural principles—a certain architectonic perception of landscape, one might say. Dan loved architecture and expressed a deep interest in it even during childhood. Moreover, he felt strongly that design was universal and that, once truly understood, the principles of spatial proportion, layering, massing, and circulation could be equally applied to both building architecture and landscape architecture. As World War II was drawing to a close, Dan, who was attached to the Office of Strategic Services, was tasked with designing the courtroom for the Nuremberg Trials. It was this important experience that led him to practice both as an architect and a landscape architect when he returned to the United States after the war.

In his dual practice, Dan applied the basic principles of designing floors, walls, and ceilings to form and articulate space in both his architectural and landscape-architectural projects; it was really only the palettes of materials that differed. His architecture was inspired, but his landscape architecture was groundbreaking—in part, I would argue, because of the architectural sensibilities imbued in his designs. His floors comprised water, native ground covers and perennials, woodland duff layers, turf, sand, gravel, stone, wood, or concrete. His walls were loggias, pergolas, and trellises, but were also formed by vines, shrubs, and trees, with buildings—and sometimes even natural landscapes—also providing “walls” in the foreground, middle ground, and background. Loggias and pergolas could also form parts of his ceilings, which were just as often conceived as tree canopies, the effects of lighting elements, or open sky.

Dan ultimately found that designing in the outdoor environment could be a much richer and more dynamic exercise than designing buildings because the latter imposed more spatial and material constraints on the process. The expansive canvas of the outdoors and the extensive palette of natural materials allowed his designs to be much more textured, layered, and majestic than those created using conventional architectural materials. And for Dan, nature itself exuded the underlying architectonic principles that inspired his work—the juxtaposition of agricultural patterns overlaid on Vermont’s rolling hills, the layering of the native plants within its forests, and the natural textures determined by the geology, soils, and moisture levels within natural environments.

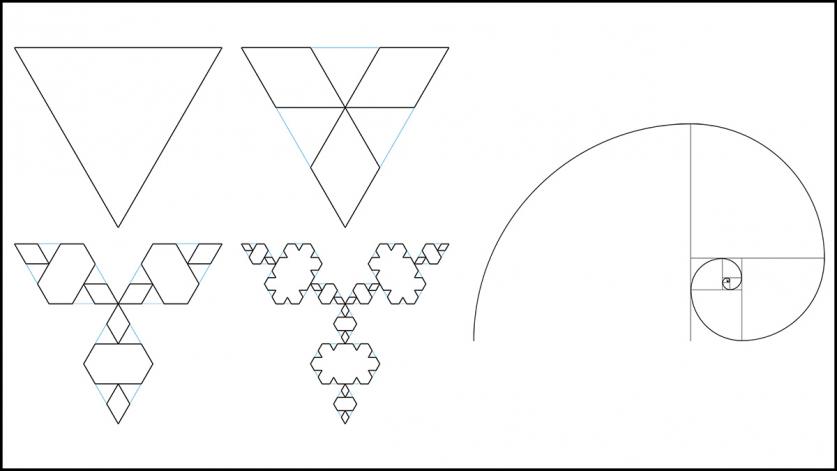

It has often been correctly pointed out that Dan was enamored with the strong geometry found in the work of André le Nôtre and that he regularly used geometric principles in his designs. As much can be discerned from the similarly between le Nôtre’s garden of the Tuileries and Dan’s grid of horse chestnuts that once graced the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. But Dan was also willing to use a more organic design approach, whenever appropriate, although these organic forms also echo geometric structures—the structures of fractal geometry. Fractals are complex geometric forms or shapes that repeat at different scales. The repetition of shapes at different scales (a principal dubbed self-similarity) is one of the building blocks of nature.

At some scales, fractals can at first appear to be random, and Dan, too, would sometimes insert random plants and trees as a contrast to Euclidean geometric forms. Creating two distinctly different geometries in one design could be very powerful. Perhaps the most obvious reference to fractal geometry in Dan’s work occurs in the landscape he created for the NationsBank corporate headquarters in Tampa, Florida—the so-called Kiley Garden. For this project, architect Harry Wolf had designed a cylindrical building with proportions based upon the Fibonacci sequence. Like fractals, the Fibonacci sequence is recursive, and its visual expression evinces the principal of self-similarity. As detailed photos show, the organization of the spaces, plants, and paving materials at the NationsBank project reflect the Fibonacci sequence writ large in the landscape. Unfortunately, the design’s detailing did not provide a deep enough soil profile, and the ongoing landscape maintenance for the project has proved challenging for this complex and beautiful garden.

Sports & Leisure

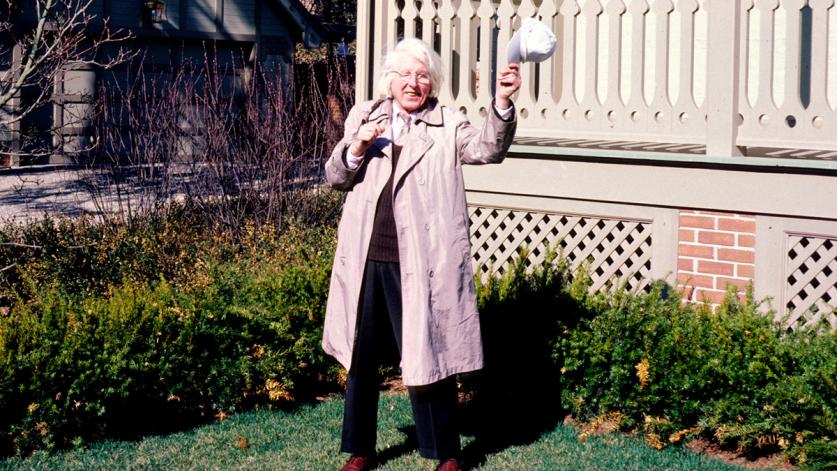

Of course, not all of life was work, even for Dan. He and Anne loved the outdoors and spent as much time as possible in nature. Their love of skiing was a life-long passion, even after they no longer skied. They instilled this love within their eight children, who all became accomplished skiers, with some even becoming instructors. Dan would often embellish his conversations by showing everyone how to make a correct ski turn. During lectures or presentations, he would regale the audience by talking about the poetry of the ski turn while illustrating, with angulated movements and gestures, exactly how to execute a proper one. He would usually end the instruction by coming to a halt and flicking an imaginary cigarette from his mouth.

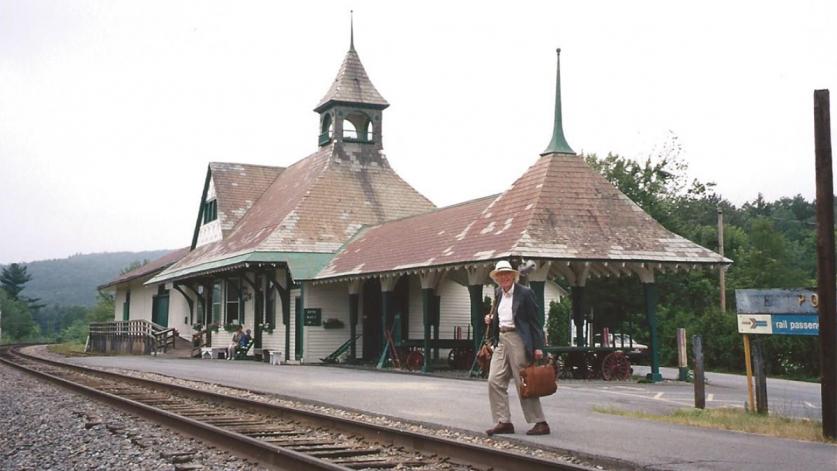

Dan also loved golf, which he took up in his late 60s, soon becoming passionate about the sport. He enjoyed the many hours of walking through the landscape that it required, even in less-than-ideal weather. He would often play golf by himself, heading out before daybreak. Dan appreciated the game’s heritage and the skill and craft required to strike the ball efficiently. He sometimes spoke of the Zen of having to relax the body and mind in order to make a good shot.

Dan and Anne were part of a small group of kindred spirits in the Burlington area—“creative types,” as some would say. Their friends included architects, musicians, artists, and industrialists, many of whom had moved to Vermont from other parts of the country. Dan and Anne enjoyed attending parties with their friends and hosted annual events at their home or office. I was lucky enough, during high school, to attend a few of the parties that the Kileys or their children hosted. One such party stands out. It was hosted by the Kileys and three other families to celebrate New Year’s Eve 1972, and was held at Shelburne Farm’s Carriage Barn, which was owned by descendants of the Webb/Vanderbilt Family. The band was Aerosmith, and the water troughs for the farm animals were converted to ice-filled champagne buckets. The band and dance floor were in the central carriage court, under the stars, while the barn was a place for mingling. These types of parties were regular occurrences and were often held to celebrate one of Dan’s epic trips. He loved to travel and socialize with sophisticated clients from around the world.

Dan was also known for hosting guests, friends, and employees for cocktails at his home, where he would ply them with his famous gin and tonics—always heavy on the gin. It would hardly take a single drink to move from stiff conversation to relaxed discussions about travel, design, Dan’s current projects, or skiing. Dan particularly enjoyed gin martinis. I remember him describing in detail the perfect garden for savoring a gin martini—right down to the proper glasses. His ‘Martini Garden’ included a woodland path planted with lemon thyme so the fragrance of the plants would complement the gin.

Dan and Anne both passed away at their Vermont home, and their ashes were spread among the surrounding forest. They lived long and dignified lives. Dan died in 2004, and Anne passed away just one year later. Shortly after Anne’s death, the house was struck by lightning and set ablaze. The fire destroyed nearly all of their belongings, and Dan’s archives from the 1980s onward. Although devastated by the loss, the Kiley children also felt that the fire was a cosmic occurrence and that their parents would have approved, seeing it as a fitting close to one chapter in a universe where everything is temporary and constantly evolving.