When the Siren Last Wails

What's in store for the aging industrial landscape of Agate Bay? At Agate Bay, a rare, natural harbor on Lake Superior’s treacherous, rock-fringed north shore, history takes material form on a giant scale.

MINNESOTA TRUNK Highway 61 runs northeast out of Duluth along Lake Superior’s rugged north shore. Before the 1920s, no reliable road ran through this area, a wilderness until the late nineteenth century. A string of towns, once hardscrabble fishing villages, were founded by Norwegian immigrants who toughed out the brutal winters because they were reminded of home. Smoked fish shops still edge the road, but quaint restaurants and antique shops have replaced general stores. Visitors needed to pack an above-average sense of adventure before the road brought a modicum of amenities. Today, mom-and-pop resorts are being displaced by glitzy lodges. With upgraded roads and restaurants, it’s easy to forget the area’s rough past. That is, until you reach the town of Two Harbors.

At Agate Bay, a rare, natural harbor on Lake Superior’s treacherous, rock-fringed north shore, history takes material form on a giant scale. Steel for the car you drive, the structure of the building where you work, and the grommets on the shoes you wear might contain iron ore transshipped at Two Harbors. Iron ore proved to be the diamond in the rough for nineteenth- century prospectors searching for gold, silver, and other minerals. Three iron ranges stretched across northern Minnesota, but the ease of open-pit mining made the Mesabi Range the mother lode. Railroads soon radiated from the mines, one terminating at Agate Bay, which, together with the adjacent Burlington Bay, gave a name to the community that sprang up at the port: Two Harbors.

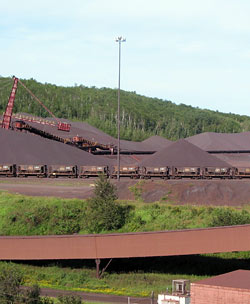

Today, Agate Bay is dominated by ore docks some four football fields long and five stories high. Hundreds of railcars perch atop the docks, having thousands of tons of taconite pellets dumped into their deep pockets. Mountains of pellets in the yard to the west are moved by colossal handlers and a series of industrialstrength conveyor belts. Trains bring the pellets from the Mesabi mines dozens of miles away. The trains thunder down from the Superior Uplands that define the horizon to the northwest, an overgrown mass of igneous rock.

Lake Superior is the biggest, deepest, coldest, and wildest of the Great Lakes, an undulating plateau of benign blue, frigid gray, or furious silver, depending on its mood. Duluth is the country’s furthest inland ocean port. Two Harbors is a few miles closer to the Atlantic. The vessels in the harbor are called ore “boats,” a diminutive term given the mammoth scale of these freighters. Their routes are predictable: Haul taconite to the steel mills of Ohio and Pennsylvania, then deadhead back for another load of taconite. Any trip, though, is subject to the foul whims of Lake Superior. The Edmund Fitzgerald (immortalized in folk song) is only one of hundreds of wrecks littering the lake’s cold bottom.

What will happen to this obsolescent industrial landscape? The question is repeated across America as the fruits of the nineteenth-century industrial revolutions wither with age.

Right now, the ore docks—and the continued operation of the taconite facility—are the herd of elephants in the living room that are too big to ignore but that no one wants to talk about.

The ships and the ore docks have a symbiotic relationship. As the size of one increased, the other was duty bound to follow. The first dock in Two Harbors, put into service in 1884, was 550 feet long and 40 feet high, could hold some 3,000 tons, and was made of wood. It initially served vessels with capacities under 1,500 tons. Rapid improvements in ship design created 7,000-ton freighters by the end of the nineteenth century. Three of Agate Bay’s five docks were lengthened to over 1,000 feet, and all were raised to almost 60 feet. There was a limit, though, to the adaptability of timber structures, particularly as locomotives and railcars became heavier.

The sixth dock rose to the challenge in 1908—the first reinforced- concrete and steel ore dock in the country and one of the first in the world. Expected to last twice as long as the 12-year life of a typical timber structure, Dock No. 6 still hovers above Agate Bay, although it was decommissioned in the 1970s. Its even more massive concrete and steel neighbors, which replaced timber Docks No. 1 and 2 in the 1910s, remain in service.

To stand on the breakwater today and watch a 1,000-foot ore boat maneuver into one of the docks is to witness the skill of a seasoned captain. Although the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has expanded the Agate Bay harbor periodically, it is a snug fit for the behemoth craft. Thrusters roil the water around the ship as it makes a right-angle turn to approach its berth. This is matched by a noisy greeting from the dock—the rumble of the shifting railcars, a clanging bell, a siren descending, again and again, in a minor tone.

The siren’s wail could be a funeral dirge for Agate Bay’s industrial legacy. That dirge had a false start in the mid-twentieth century when the richest ore had been taken from the mines and competition from overseas was increasing. The massive railroad maintenance shops adjacent to the docks were abandoned in 1962 when operations were consolidated in Proctor, near Duluth, a prelude to the closure of Agate Bay’s docks the following year. But the docks were resuscitated in 1966 thanks to antheemerging market for taconite, a low-grade iron ore left after the best deposits had been taken from the Mesabi. Taconite is dispersed throughout a hard rock and is difficult to extract. And when it is extracted, the fine particles must be agglomerated into a usable form: pellets slightly larger than rabbit droppings. These pellets, processed near the mines, ride the rails to Agate Bay.

Tacnoite Storage Area

The community’s good health, though, was far from guaranteed. Demand for iron ore continued to swing up and down, and competition from Asian and other sources intensified by the late twentieth century. The ugly specter of consolidation haunted Agate Bay as economic realities hit the Duluth-based railroad company that owned the docks, the taconite storage area, and the vacant railroad shops. The railroad’s holdings also included land ringing the harbor that the community had come to think of as theirs, with a railroad depot-cum-historical museum, attractive nature trails, a boat launch and parking area developed by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, and even the city’s wastewater treatment plant.

Two Harbors had always been a company town, with nearly 95 percent of the community’s workforce employed by the railroad by 1900. But that relationship was shattered in January 2003, when Two Harbors woke to discover the railroad’s sale of nearly everything, save the docks and the taconite storage area, to Sam Cave, a private developer from a Saint Paul suburb.

Cave soon announced plans for townhouses and a hotel/conference center on Lighthouse Point, a rugged peninsula separating Agate and Burlington Bays. The decommissioned lighthouse complex at the tip of the peninsula, a National Register-listed property, is now operated as a bed and breakfast by the local historical society.

The initial phase of the project is three condominium buildings with a maximum of 75 units between them. Although the Environmental Assessment Worksheet for the project says, “The general site development framework shall draw upon the local architecture and waterfront elements to create unique elements to enhance the project,” it also says, “Architectural materials will be a mix of stone and wood. Using these elements, the designers will further the project by using Two Harbors’ most common building type, Arts and Crafts buildings.” Arts and Crafts is trendy and fits the romanticized view of the North Shore; a design that played off edgier industrial forms might not sell as well. The worksheet also makes it clear that the craggy terrain will be tamed: “Drilling and blasting may be required for construction of utilities and the building.”

Local reaction to the plans has been mixed. In September 2003, at a city zoning and planning commission meeting considering Cave’s rezoning request for the condominium development, one resident groused: “I’m upset that the railroad seemed to pull a fast one.” Another warned: “Two Harbors shouldn’t be so hungry for development that it forgets its community heritage.” But others agreed with another resident, who observed that “this is the best scenario we could come up with.” Comments at a June 2004 planning meeting ranged from “Two Harbors needs development on the waterfront in order to spur economic development” to “housing on Lighthouse point is a poor idea due to bad weather and sewer plant smell.” As Saint Paul Pioneer Press columnist Nick Coleman wrote in June 2003: “Whether you see a place like [Lighthouse Point] as needing preserving or as too valuable to let lie fallow probably depends on your pocketbook, your politics, or your personal beliefs.” No one seemed to consider the long-term implications for the bay as a whole. Perhaps the residents felt powerless to do so. The city boundary stops at the railroad property, leaving the ore docks and Pork City Hill beyond its legal jurisdiction.

IN THE AGE OF THE AUTOMOBILE, visitors are greeted at the outskirts of Two Harbors by a barrage of fastfood restaurants, big box stores, and car dealers. Two motels flank a cemetery, a remnant of the days when this was a transitional space between civilization and the great wilderness beyond. Today, it is easy to drive through Two Harbors and completely miss the harbor and the traditional downtown—which, surprisingly, has always turned its back on the harbor.

But maybe that is not so surprising. While the docks appear sculptural to the visitor, they hold other meaning to those who worked there, confronted daily by the grime and danger of an industrial operation.

Two Harbors railway depot

There are some historical artifacts that the community has chosen to preserve. The railroad station midway between downtown and the waterfront has been converted into a museum and community center. Beside it are two lovingly maintained locomotives, tucked under shed roofs for protection against the elements. The Edna G., a steam-powered, coal-burning tugboat that worked the harbor from 1896 to 1981, continues to be berthed near Ore Dock No. 1 after a proposal to put her in permanent dry dock failed.

The ore docks, looming somberly above the harbor, remain the primary character-defining feature of Agate Bay today. But what will happen to this obsolescent industrial landscape? This question is repeated across America and throughout the world as the fruits of the nineteenthcentury industrial revolution wither with age.

Sometimes, market forces take over. The abandoned mills that once made Minneapolis the flour capital of the world are being resurrected as luxury condominiums, pricey offices, and a state-of-theemerging market for taconite, a low-grade iron ore left after the art museum. The adjacent riverfront, a dumping ground for decades, has been spruced up and added to the city’s extensive park system.

Another approach is being adopted in Germany’s Ruhr Valley, where the muscular factories that awed the world are now rusting dinosaurs. With too much to clean up and neither the money nor the will to do it, there was room to let another vision come into focus. At the innovative Landschaftspark in Duisburg, coalbunkers are used to teach rock climbing, a gasholder has been retrofitted into a diving tank, smokestacks are a giant canvas for an artist’s dynamic lighting installation, and huge areas are returning to a natural state.

But Germany’s tourism industry operates year-round on a giant scale in the heart of Europe. The success of nontraditional tourism destinations in relatively isolated and weather-challenged locations, such as Lake Superior’s north shore, is far less assured.

In Two Harbors, some attempts have been made to convert surplus industrial facilities for other uses. The vacant railroad shops attracted manufacturers of locomotive components and mail delivery trucks, but the ventures failed. By the 1990s, the shops were slated for demolition and given their last rites: documentation for the Historic American Engineering Record. Despite the threat, the shops still stand, handsome brick structures that would, in another setting, be prime candidates for adaptive use. But for Agate Bay, a sadder fate seems likely.

The railroad’s sale of land to the developer earned Agate Bay a place in the Cultural Landscape Foundation’s “Landslide” list of endangered working landscapes. The list includes properties diverse in age, location, and type: from Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico, inhabited continuously since the late 1300s, to Ridgewood Ranch in Willits, California, the home of Depression-era horseracing legend Seabisuit.

But what’s the fuss all about? It is reasonable to question the value of saving the aging skeletons of an earlier industrial revolution, especially when doing so might impede innovation today. Not all obsolete industrial landscapes can or should be saved. The economic bottom line, the dasher of many dreams, is a reality that cannot be ignored. Not every old industrial site has a fairy godmother in the form of a developer or a sugar daddy with access to pork-barrel appropriations. And even fairy godmothers and sugar daddies die, sooner or later. Or they want to change their beloved into a new creature, as is the case at Agate Bay.

Right now, the ore docks—and the continued operation of the taconite facility—are the herd of elephants in the living room that are too big to ignore but that no one wants to talk about. A June 2004 waterfront planning study conducted by the Two Harbors Planning and Zoning Commission and the Arrowhead Regional Development Commission included most of Burlington Bay but stopped at the city’s west boundary—leaving out half of Agate Bay. A series of waterfront planning reports going back to 1978 displayed the same myopia. Even a local antidevelopment activist was taken aback when asked his opinion about the effects of the development on the historic docks; citizens concerned about the development, he said, had focused primarily on maintaining public access to Lighthouse Point.

On an aerial photograph entitled “Current Future Scenario,” the waterfront planning study concedes that the area of the proposed condominium development could be “future hotel/housing or preserved as green space,” while recommending that the green space and trails on Lighthouse Point be maintained. The plan shows a marina on the old coalyard, with an “open space/festival park” immediately to the west. But the community’s ambivalence about its relationship with the ore docks and railroad yards is communicated by labeling the vicinity of Van Hoven Park, which abuts the still-active rail facility, as “unclear area.”

The railroad has always been secretive about its plans. In the days of prosperity, its paternalism was benevolent, but its temperament has become less reliable as the ore industry has weakened. The sale of land to Sam Cave does not seem to have rallied the community to take ownership—figuratively, if not physically—of the future of the other half of Agate Bay. True to form, the railroad is not volunteering any information, and it appears that no one is prodding them to do so. Maybe local residents are continuing in historic roles, not wanting to upset the town’s historical boss and patron. Maybe they’re afraid that by asking, they would be rudely awakened from their dreams that the railroad will continue in operation forever, sustaining at least a modicum of economic activity for the community.

For the time being, at least, it appears that the railroad is holding onto the docks and their industrial use could continue indefinitely. Based on the recent sale of the Agate Bay land, however, their long-term operation is questionable.

And even if they remain in use, will there be conflicts with the new inhabitants of the bay— like the exurbanites in their new McMansions who complain about the smell of the century-old farm’s barnyards next door? Maybe the ore docks can live harmoniously with modern condominiums. Maybe, given the differences of construction and materials between then and now, the docks will outlive anything anyone plunks in their viewshed today. And maybe the docks will go. But without them, without the railcars hauling taconite from the mines and ore boats making the milk run to Eastern mills, Agate Bay will be just another pretty harbor with a coldwater beach.

That such a massive resource can be so fragile, so subject to the fickle moods of forces big and little, near and far, is worthy of more than a passing thought. Obsolescent industrial landscapes can be more than sculpture or little more than a scrap heap, depending on your perspective. Perhaps one of their most valuable services is as a Rorschach test writ large, providing insight into your aesthetic tolerance, your judgment on history, and your vision for the future.

This article originally appeared in the April 2005 issue of Landscape Architecture magazine and is reprinted with the permission of the author.