Grave Landscapes: Documenting America's Rural Cemeteries

Grave Landscapes: The Nineteenth-Century Rural Cemetery Movement, a forthcoming publication from the University of South Carolina Press, documents the practical, cultural, religious, and design influences that shaped the creation of America’s rural cemeteries. The book examines the extent of the rural cemetery movement, details its design characteristics, and places it within the broader context of American landscape design. Sharing a goal of The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF), the new book aims to provoke interest in and facilitate the identification and preservation of America’s rural cemeteries—a widespread and influential landscape type.

In eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century America, growing cities faced burial crises at the centers of their communities. As the populations of industrializing cities swelled, small urban graveyards—often connected to churches—filled beyond capacity. Unkempt graveyards in Boston became “saturated with remains.” In Pittsburgh, they became so densely populated that “it was scarcely possible to open a new grave without desecrating the remains of some one previously interred.” Deteriorating conditions spurred mounting moral repugnance and public health fears. Charleston’s mayor told that city’s citizens that it had been proven that “putrid miasmata” emanated from graveyards to spread disease. Moreover, he lamented that the city’s graveyards invoked “little or no reverence for the dead.” Back in Boston, an 1826 ordinance closed three of the city’s main burial grounds—the Granary, Central, and King’s Chapel—to new burials and restricted Copp’s Hill Burying Ground and the South End Burying Ground to temporary interments. The increasingly untenable conditions precipitated innovative thinking and, ultimately, a solution.

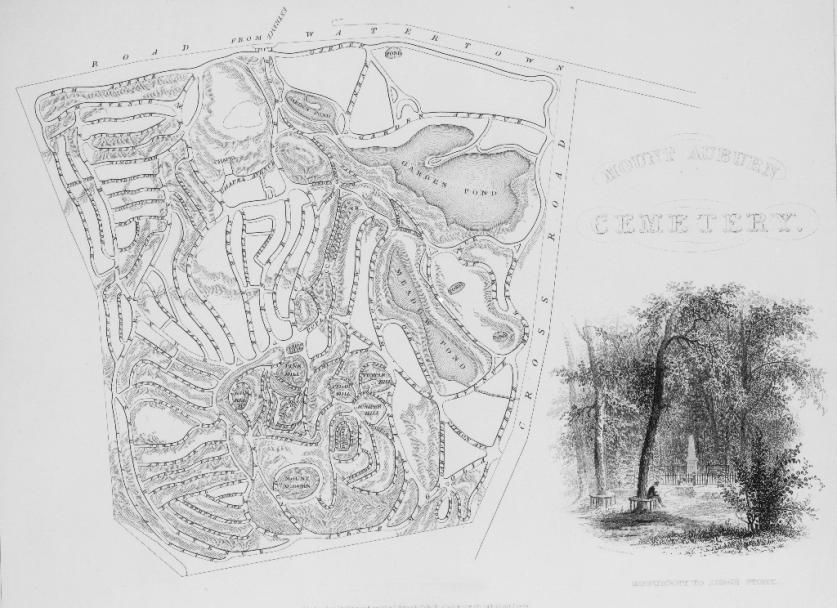

In 1825 Dr. Jacob Bigelow gathered a group of prominent Bostonians together to consider a new type of burial ground—one that “might at once lead to a cessation of the burial of the dead in the city, rob death of a portion of its terrors, and afford to afflicted survivors some relief amid their bitterest sorrows.” Bigelow, who was also a botanist, presented a general concept for a burial place outside of the city “composed of family burial lots, separated and interspersed with trees, shrubs, and flowers, in a wood or landscape garden.” It took several years, however, before the pioneering idea finally became a reality. In 1831, Bigelow enlisted the support of the newly formed Massachusetts Horticultural Society to purchase a 72-acre tract of heavily forested land in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for an ornamental burying ground. The founders named it Mount Auburn and officially dedicated it as a rural cemetery.

Drawing inspiration from English landscape gardens and the Parisian Cemetery of Père Lachaise (1804), General Henry A. S. Dearborn, the founding president of the Horticultural Society, laid out Mount Auburn’s grounds in the Picturesque style. He created a circulation system that followed the existing uneven topography of the site and included a dizzying maze of footpaths along which cemetery visitors could wander contemplatively among “bower-sequestered” gravesites. In time, Picturesque structures were added to the grounds, including a monumental Egyptian Revival gateway, a Gothic Revival chapel, and a striking 62-foot-high tower from which visitors could survey the expansive site and surrounding countryside. Mount Auburn’s founders encouraged the addition of sculptural commemorative monuments to family burial lots and, at least at the outset, the addition of iron fencing around them. They also supported the inclusion of civic memorials to celebrate America’s heroes. Before the United States had public art museums, Mount Auburn acted as an extensive exhibit space where sculptural works were displayed for visitors to admire.

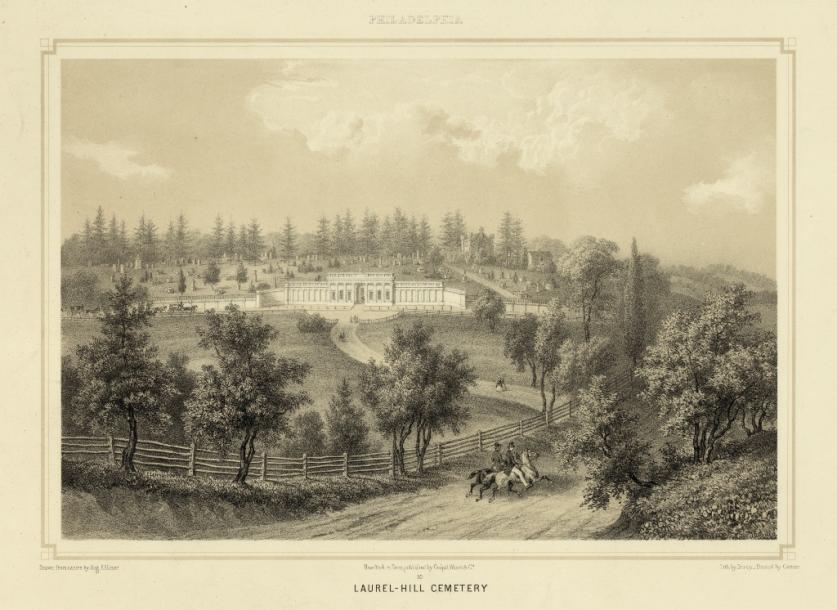

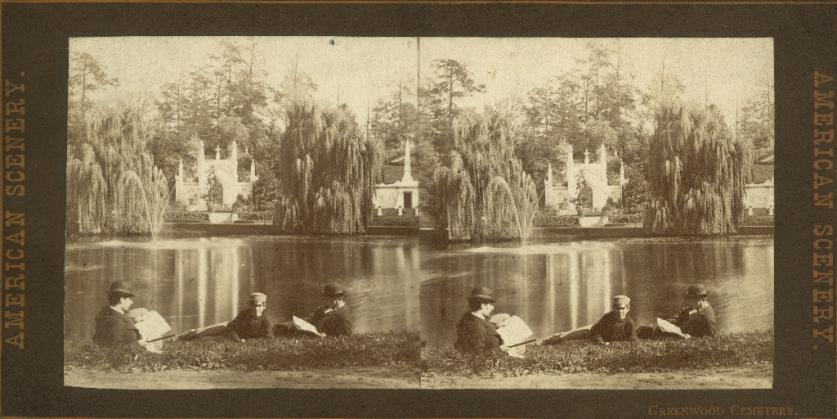

Before long, Mount Auburn Cemetery captured the imagination of the country and inspired growing cities to adopt this groundbreaking model. Landscape gardening tastemaker Andrew Jackson Downing commented at mid-century that “no sooner was attention generally roused to the charms of this first American cemetery, than the idea took the public mind by storm.” The 1830s witnessed the development of at least ten rural cemeteries in the Northeast. In 1834 Mount Hope Cemetery was incorporated in Bangor, Maine—a city that had ambitions of challenging Boston as the financial and cultural hub of New England. Two of the most often cited rural cemetery examples followed—Laurel Hill Cemetery (1836) in Philadelphia, and Green-Wood Cemetery (1838) in New York. The 1840s saw the increasing proliferation of the new burial landscape type and its migration south, beginning with Rose Hill (1840) outside of Macon, Georgia. With the expansion of canals and the extension of railroads into the Midwestern hinterland, rural cemeteries became a repeated feature throughout that region as well. Ohio saw the establishment of Woodland Cemetery in Dayton (1841), Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati (1844), and Green Lawn Cemetery in Columbus (1848). Meanwhile, the passage of the Rural Cemetery Act by New York Legislature in 1847 spurred the creation of new large-scale cemeteries in that state. Cypress Hills Cemetery (1848) and The Evergreens Cemetery (1848) were founded in Brooklyn, Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo (1849), Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Tarrytown (1849), and Forest Hill Cemetery in Utica (1850), just to name a few.

Rural cemeteries were widely embraced as restorative retreats where visitors could commune with nature at a time before America’s cities had dedicated public parks. As critics became increasingly vocal about the inappropriateness of cemeteries serving as pleasure grounds, Downing asserted, “Judging from the crowds of people in carriages, and on foot, which I find constantly thronging Green-Wood and Mount Auburn, I think it is plain enough how much our citizens, of all classes, would enjoy public parks.” Moreover, he advocated that public parks emulate the rural design of the country’s celebrated cemeteries. Downing’s rhetoric struck a national cord and helped propel the establishment of naturalistic parks within America’s cities and extend the rural cemetery movement’s impact on the landscape.

Grave Landscapes, co-authored by Erica Danylchak and James R. Cothran (1940-2012), will be available January 31, 2018.